Assisted Death: Maturely Making Death’s Decision

Making the Personal and Educated Decision to Die

Imagine for a moment being at a point in your life where it is no longer desirable in the face of opportunity for a comfortable and controlled death.

It seems nearly impossible, in my mind, to be truly comfortable with the idea of your own death. Now, I am a young student who’s still in that phase where we don’t really think about our mortality, but regardless, this question is not and never will be an easy one to face.

It is a question Jean Truchon (51), and Nicole Gladu (74), have been asking for quite some time now. Truchon and Gladu have been suffering from rare degenerative disabilities, lacking the use of most of their bodies. And after nearly nine full months of fighting for their right to make this choice for themselves, they have finally been given the bureaucratic blessing of access to an application to die.

Most Canadian provinces have medically assisted death laws, all following roughly the same guidelines and requirements: “Natural death must be reasonably foreseeable.” This prerequisite works for some. However, it ultimately neglects those who could feasibly survive long periods of time, but may not want to.

Here, it’s important to draw a distinction between voluntary and autonomous death and, well, straight up suicide.

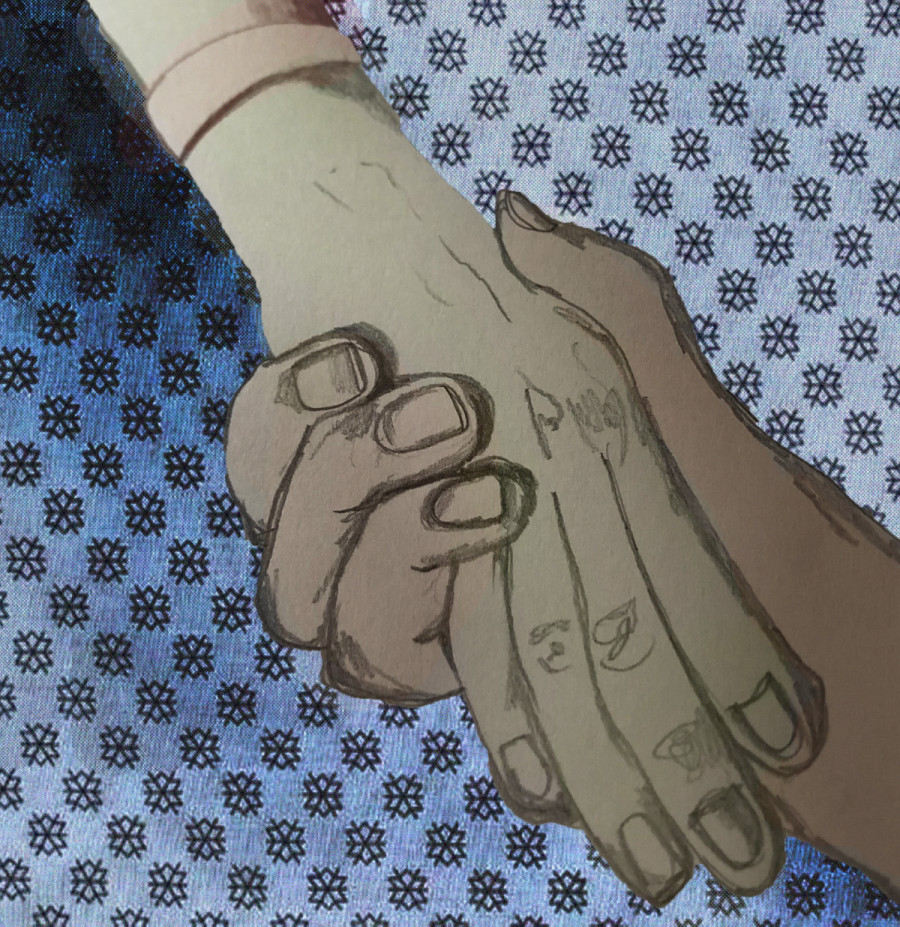

Let’s look at the situations of assisted death most commonly found, and therefore not often given public attention. I’ll use a personal example—something that happened a couple years back, and really changed my perception of life, death, and family.

My grandmother was diagnosed with intestinal cancer when she was 84. It quickly spread throughout her body, to the point where she knew that there wasn’t much life left for her to live. She decided rather than letting her body and mind deteriorate over that time, she would book the date of her death and have her two sons with her in her last moments—as prepared as they all could be for such an emotional part of life.

This was in British Columbia, which has arguably the least restrictive laws surrounding assisted death, but this situation is a common one throughout Canada. My question is, where is the line drawn between reasonably foreseeable, and what the provincial government views as essentially suicide? If you or someone you knew had two weeks to live, and they had the opportunity to go out in a clear and content state of mind, we wouldn’t question it.

But what about three weeks? A month? Two? A year? At a certain point, the timeline begins to reveal itself as arbitrary. In other words, following this logic is endless, and will never lead to a clear cut definition of “reasonably foreseeable.”

Unfortunately, this problem doesn’t have only one solution. I believe that all of us deserve the right to autonomy, and therefore when it comes to life and death, it’s only fair to treat each case as unique as the people they involve. That is, assuming they’re in a coherent state of mind, and y’know, able to actually speak for themselves.

These are not cases of suicide. I, and I’m sure many of you too, have sadly felt suicidal at one point or another, so we can attest to the differences between those wanting access to assisted death, and the sadness and despair of wanting to end your life to escape it. In the case of assisted death, we’re talking about people who have lived, and are making an incredibly personal and educated choice.

It’s cases like Truchon and Gladu’s that make this clear. This means a more careful approach from doctors, and a more tentative ear from judges not only in Quebec, but Canada wide. What we as humans care about is the quality of life, and the quantity of it. So, what do we do when the quantity inversely affects the quality?

_600_375_90_s_c1.JPG)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)