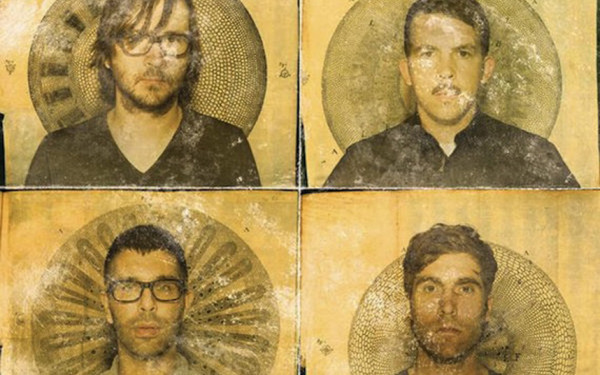

Andrew Jackson’s Photographic Look Into Jamaica and Montreal

Photographer Explores Migration, Memory, and Ubanism

Click.

It’s a long exposure photo.

And everything slows down.

The wind runs invisible ribbons through the tall grass in the planters of de Maisonneuve Blvd.

Even the sound of the shutter is perceptible as it winks its eye shut.

“The camera is a passport into your lives,” says Andrew Jackson, as he gazes down the long hallway of Concordia University’s Hall building.

Born in the small town of Dudley, near Birmingham, Jackson has captured images of his British homeland for outlets like The Guardian and The Financial Times Magazine.

In February, Jackson will spend a month at New York’s Syracuse University as an artist-in-residence for its 2018 Light Works Residency.

His work will be published in their special edition, Contact Sheet: The Light Work Annual. He is also the co-founder and co-director of Some Cities, a community interest company, which is a participatory initiative aimed at creating opportunities for skill-learning and narrative sharing via photography. Jackson was also the winner of the non-profit agency award, Multistory Bursary 2018.

1_900_734_90.jpg)

But today, as the recipient of the Artist International Development fund from the Arts Council of England, he is in Quebec, getting rewarded for his photographic works taken in Jamaica and Montreal.

“If I stared at someone for five minutes, they’d box me; but as a photographer, they let me into their lives–they tell you intimate personal details,” he says. “They’re not telling you, though, they talk to the camera.”

The camera is a temporary space—a portal with two facing doors, if you will.

The shutter click is the moment when both of those doors are open, and when Jackson gets to take a peek into someone else’s world.

And that is the exact thing that he’s been exploring in his current project that focuses on migration, memory, and notions of urbanism.

As Jackson moves through different urban spaces and documents them one photographic still at a time, he finds himself with another lens in his tool kit, one of ethnography. Each city provides its own distinct narrative about how humans have moved through space; in turn, these spaces tell stories that knit a unique psychological tapestry of its inhabitants.

A graduate from Newport University in Wales, where he underwent a masters in their documentary program, Jackson explains that there are 148 different ethnic groups in Birmingham.

2_900_734_90.jpg)

If I stared at someone for five minutes, they’d box me; but as a photographer, they let me into their lives–they tell you intimate personal details. They’re not telling you, though, they talk to the camera.” —Andrew Jackson

“You’ve got people speaking different languages, different dialects of those languages, different religions.” He pauses and sincerely asks: “How do you get a society to work when you’ve got so many different identities taking space in it?”

Montreal provided just the urban avenue for such exploration. Home to a population that, according to Canada’s 2016 Census, is 53.4 per cent Francophone, 15.1 per cent Anglophone, and more than a third Allophone. It became the obvious place to explore the phenomenon.

This kind of “super-diversity,”—a term coined by American anthropologist Dr. Steven Vertovec—is becoming increasingly common in urban societies because of globalization and transnational movement. Urban environments have provided rich soil and fertile spaces for ethnic diaspora to form roots.

But how do roots develop in foreign lands?

Jackson’s trip to Jamaica earlier this year was an attempt to answer this question all while discovering his own roots.

He talks about trying to capture a record of his parents’ existence before they made their transatlantic trip to England in the 1950s.

What was this country where they grew up?

What was the house they grew up in like?

Where did their stories come from?

But the streets have since disappeared from the last time his parents were there—that’s what Jackson discovered when he tried to follow his father’s directions. His chuckle fades as he spins out a question that is unintentionally bittersweet. “How do you tell your father that his route home has disappeared?”

And thus his project in space, diaspora movement, and psychological migration was born.

In a talk given several years ago in the DB Clarke Theatre, Concordia’s Dr. Sherry Simon discussed this in-between world of the immigrant who stays. They are seemingly always the “Other” in the land they’ve adopted, but are also keenly aware that they no longer fit into the country where they were born and raised. Simon compared their movement to that of the St. Lawrence river–an endless ebb and flow of identity.

4_900_734_90.jpg)

Who changes, though? The person or the places that get left behind because of migration?

Jackson wonders what happens when people stay and don’t go home.

“Immigration is often talked about only in terms of people coming, not about them staying or retiring,” he said.

“It’s almost as if they don’t make roots. How long can you keep calling them migrants?”

Since embarking on this journey, what has struck Jackson the most is the sustained invisibility of visible minorities. He remarks how easy it is for marginalized people to be made invisible, to go through life unseen, ignored and to be easily erased from the lives of those who belong to dominant communities.

In this sense, geographies are more than just physical space, they can be cultural and they can also be emotional.

Psychogeography—as explained by French philosopher Guy Debord—reveals how individuals are affected by their living environment. The emotions and behaviours that a physical space can elicit from its citizens can be wholly intentional or not.

Montreal is no stranger to this concept, as Bill 101 ensured that the visual linguistic landscape of la métropole would very clearly reflect its cultural values.

For those who migrate and who dare to not be silent about their erasure, what then?

Where do their voices fit in a narrative that would actively exclude them?

Finally, on the ninth floor of Concordia’s Hall building, Jackson has come to visit ghosts. Just under 50 years ago, a sit-in that lasted for 10 days was staged on this very floor that implicated over 400 undergraduate students, and has since been called the largest student uprising in Canadian history: The Sir George Williams Affair.

Nine international students who migrated from the Caribbean reported the racially-biased grading practices of their biology teacher. It did not take long for the administration to completely disregard the students’ charges and exonerate the professor from any malfeasance.

The administration never made contact with the students.

In the face of erasure, the students chose to be visible and vocal, and paid the price. According to all accounts, the sit-in only became a “riot” once police arrived on the scene.

Almost 100 students were arrested. Some were deported, and others fled the country.

“It’s a deliberate process and never an accident,” he said.

Jackson places his tripod down in front of the sprawling open space of the ninth floor hallway. Once locked into place, he turns to his camera case, opens it and exposes a perfectly nested line of small, yellow cylinders of Kodak film.

He develops each picture by hand.

“Sometimes you’ll spend all day taking pictures and not one will come out well,” he says.

He laughs softly as he moves through the ritual motion of drawing the film out, feeding it into the camera, and then closing the camera’s back.

Today, the sound of feet scurrying to the class fill the hallway where there had once been a melee of chants and defiance.

Hallways, by their nature, are not a migratory space. They are rarely a resting place. Instead, they’re a place where bodies pass through before finding their final destination.

Click.

In just a millisecond, Jackson has imprinted this space of transition onto his film, and will fly it back to his island —even the ephemeral can take flight transnationally.

“Not all migration takes place across international borders,” he says. “But all migration is followed by psychological change, I believe.”

3_900_734_90.jpg)