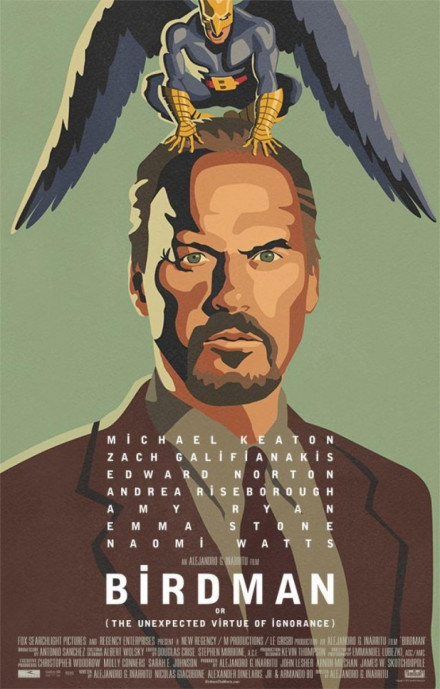

The Double Edge of Relevance: Iñárritu’s “Birdman”

As a theatre geek, I was more enthralled with Alejandro Iñárritu’s masterpiece Birdman than, say, The Boyfriend sitting next to me trying to cop a feel during the last 25 minutes (I mean, who hasn’t in a dark theatre watching a seemingly dreary hollywood drama?) wondering idly if the movie was almost over.

Iñáritu’s Birdman tells the story of a washed-up actor (played with distinction by Michael Keaton) struggling to stay relevant amidst the “cultural genocide” of the Marvel juggernauts and social media titans. A cultural icon of the ‘80s, Riggan Thomson puts his heart and soul into a production he wrote, directed, and starred in (a production which is unfortunately and obviously a thinly veiled parallel of his own life) hoping to create art from the fragments of his past life as a mass-produced, all-American family-approved consumerist good.

However, his highly-developed schizophrenia (also apparently residual telekinesis from playing Birdman) and consequent unreliability as a narrator makes the audience wonder whether or not he even cares about making art, forcing the audience to question whether art itself can have any relevance.

I had mixed feelings about Keaton’s character. Clearly he cared about his craft, but his desire to stay relevant in a society that turned him into a cult icon and had all but forgotten him overshadowed any possibility for him to truly be considered an “artist.” But what’s the mark of an authentic artist anyway? According to Iñárritu, it doesn’t even matter. All that matters is that you put everything you have into your craft and do the absolute best that you can (Oh no, this review just got suspiciously self-reflective).

Iñárritu’s production was a satire of a satire on art that was able to make fun of people who decide what art is and isn’t, while simultaneously presenting itself as a Hollywood drama under the guise of an art house movie. It made fun of everyone and everything, from Justin Bieber to the entire Marvel universe (taking a few jabs in particular at Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark).

Ultimately, this was a movie about not being forgotten, culminating in a painful minute-long segment of Keaton unabashedly walking around Times Square in nought but his tighty-whities whilst passersby flock about in droves, filming and documenting every humiliating moment. It may have been possible to be forgotten 20 years ago, but the advent of social media and accessibility to WiFi and 3G everywhere has allowed every instance of our lives to be perpetually available on the Internet.

During a shouting match with his daughter, played by a barely recognizable Emma Stone (though that may have been due to the fish-eye lens used to film the whole movie, to great effect), Riggan is forced to confront the reality that he doesn’t matter anymore and the only way to resurface is to throw in the towel and join the masses on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

The film also touched upon the continuing debate between stage and screen: which is the purer art? It’s true that film allows for more room to manoeuvre (multiple takes, fed lines) while the stage is immediate (if you mess up, everyone will know). Although film demands an incredible ability to pretend, particularly on the actor’s part when, for example, acting in front of a green screen, there is a sense of heightened reality when acting on stage; it is truly in-the-moment and can feel real in the way that no screen production can.

With unflinching shots that could last up to five minutes, the cast and crew of Birdman managed to recreate the heightened reality of a staged production with the edgy yet graceful feel of an indie movie. Accompanied by erratic and electric jazz drum beats, juxtaposed with Strauss-esque orchestral breaks during moments of recollection of past triumph, Iñárritu’s Birdman is sure to be a contender in the Gladiator arena of the 80-somethingth annual Academy Awards.

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)