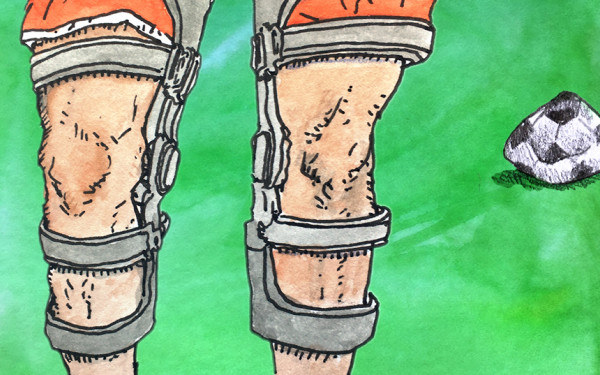

Women and ACL injuries: A growing problem

The reasons behind women’s higher rate of ACL injuries goes beyond gendered anatomy

Mara Gruber, 18, played at club-level most of her childhood in Australia. However, she had to stop at 14 after many injuries, including an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear.

“I loved playing in a club but knew I would never become a pro. I was too injury-prone,” she said. “I did some reeducation, for sure. But I never got operated on. I spent about six months on all kinds of painkillers. I still played despite everything, but only for fun,” she said.

Like many others, Gruber thinks ACL tears are plaguing the game. “Being a woman in soccer is very difficult already.”

Sam Kerr, Teya Goldie, Caroline Weir, Faye Kirby—these are only a few names of women’s soccer players who recently suffered an ACL tear. About 195 elite women’s soccer players suffered from this injury in the last 18 months alone.

The ACL is a crucial leg muscle inside the knee that helps with rotational movement and is prone to tearing with sudden movements. According to University of Manitoba researcher Dr. Joanne Parsons, they are relatively common in any sports at all levels, whether you’re a recreational or competitive athlete.

ACLs can tear for various reasons and are more often linked to basketball, lacrosse, gymnastics and soccer. In soccer, the players’ lateral movements and sudden changes of direction cause stress on the ligament. Simple movements like passing the ball need rotation and a velocity higher for soccer players than any other athlete. Contacts between players also exacerbates this constant threat.

Statistically, women athletes are two to eight times more prone to ACL tears than their male counterparts.

Physiology, hormones, even bone structure all differ between men and women and contribute to women’s higher risk of ACL injuries.

Women’s joints tend to be more lax than men’s, which plays into the risk. The laxity of the ACL also differs with hormones. One 2002 study demonstrated that the prevalence of ACL injuries tends to follow the menstrual cycle. Another 2017 study showed that this was due to progesterone’s impact on the laxity of the ligaments in the knee.

Some other factors include different hip structures in men and women, where women’s hip bones are wider, causing a bigger inward force on the knees, and lower testosterone levels which impact muscle mass.

Nonetheless, physical differences are not the only cause for women’s higher injury rate.

Women’s soccer’s popularity is growing unprecedentedly. According to the FIFA Women’s Football MA Survey Report 2023, the number of women playing organized soccer has increased by nearly a quarter compared to 2019 (up to 16.6 million). The discipline now attracts many more fans. Arsenal sells out stadiums while the 2023 Women's World Cup’s audience is higher than ever, with about two million tickets sold and two billion viewers, a staggering 79 per cent increase from the last tournament.

This rapid development of the sport has, however, come with downsides. The more the public watches the games, the more quickly the market has to adapt to this new demand, and to many, the growth is too fast to adapt safely.

Calendar issues are not only women's issues. But women players have not been playing professionally for as long as men. As they are not used to playing as frequently as men, such a rapid and busy schedule can be brutal for new professionals and older players. Usually, women get into the soccer professional world later than men, as the academies are not as developed in every country.

The online exhibition More than Medals dives into the struggles female athletes face. The exhibition, self-described as “a research-based exhibition exploring five gendered environmental challenges shaping women’s injury in elite sport,” is a collaboration between the University of Nottingham and the UK Sports Institute.

To the More than Medals research team, the uneven societal treatment between men and women might amplify the misunderstanding around injuries. They added that stereotyping women as weak or paranoid could also downplay injuries.

Additionally, worse training facilities than the men’s teams and unrealistic female athletes' standards all indirectly lead to higher risks of injuries, and especially its complications, such as rehabilitation.

Parsons, who was involved with More than Medals, thinks weather conditions, genetics, coaching decisions, poor-quality fields, ill-equipped weight rooms, working another job and referee decisions also contribute to women’s ACL injuries.

“Those who are saying ACL injuries are due to ‘q angle’ or ‘wide hips’ or any other single factor. Give your head a shake. It’s so much more complicated than that,” she tweeted. “We have to be missing something.”

For young and older teams, coaches must adapt their training sessions differently for women and men.

Tony Perrier is the head coach of both the Université de Sherbrooke Vert et Or women’s soccer and men’s soccer team. He has coached girls for most of his career, but the training he does with men and women differs.

“Our staff needs to adapt. We try to consider all factors that might lead to injuries. You shouldn’t coach girls the same way you coach boys,” he said. Perrier added that he and his staff take measures to prevent injuries, such as tracking the players’ menstrual cycle and keeping records of injury history, and adapt their training. “It’s the little details that add up, like certain cleats that are not adapted well to women,” he said.

“I’ve had a player tear her ACL during my second year at Sherbrooke,” Perrier added. “It happened on a field that we shouldn’t have played on, badly maintained. It healed, but she had to quit and stop playing at an academic level, as it is very demanding.”

In the past, a torn ACL often meant the end of a career, according to Parsons. “It’s devastating. [ACL injuries] can be life-altering for people, not just the immediate pain and lack of ability to participate in their sport. But people who experience this injury often have to have surgery. The rehabilitation, whether you have surgery or not, can take nine months or more. And then, you end up with increased risk of developing early onset osteoarthritis,” Parsons said in an interview for Science Friday.

Even so, according to research, odds of returning to sport after an ACL tear within five years is 25 per cent lower.

However, relapse is possible, and it happens. American soccer player Megan Rapinoe tore her ACL no less than three times. Rapinoe showed that, while recovery is possible, relapse is also very common.

Women’s higher risk of ACL injuries are not just physical and consider gender-based inequities and unsuitable playing environments. Despite this, extensive research conducted on ACL tears signal a brighter future for women’s soccer as the discipline continues to grow bigger.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 12, published March 19, 2024.

_800_2000_90.jpg)