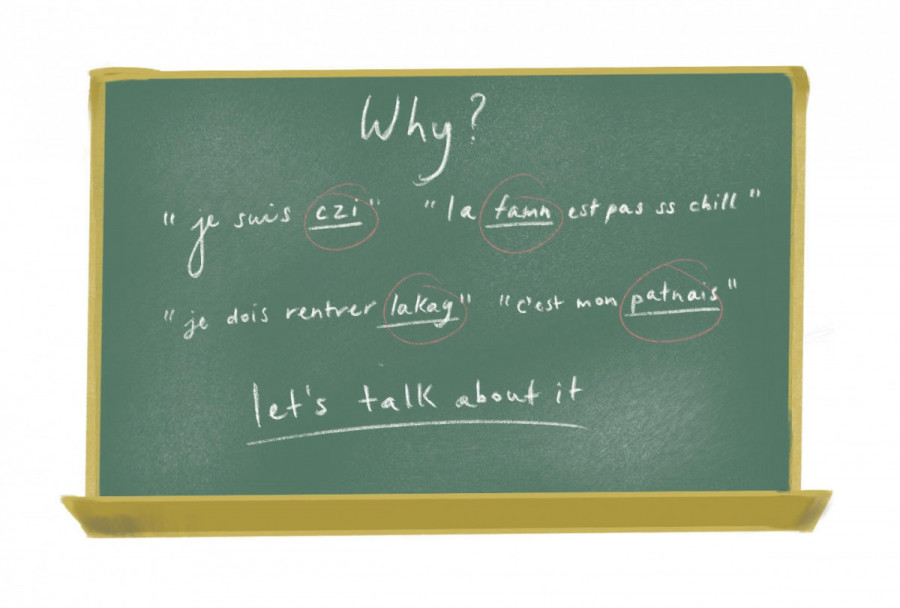

When Did Haitian Resilience Become Fun?

An Honest Assessment of Linguistics Within Montreal’s French Vernacular

In high school, my identity as a Haitian was especially odd to navigate in a predominantly white institution.

Whether it was my hair or the food I brought to school, I was constantly reminded that major parts of my culture did not fit in. All of it was scrutinized by my white counterparts, and was often mocked.

Imagine my shock when one of the white boys in math class tapped my shoulder and called me “djol-métallique”—djol meaning mouth (derogatory) and métallique, meaning metallic (I had braces at the time). This kid not only had the audacity to misuse my language to berate me, but then asked me to give him a rundown of all the Creole (Kreyòl) insults I knew. This type of interaction has kept recurring throughout my life. The conjunction of Kreyòl and French Quebecois is vastly spread out today. However, when asked if they know where their borrowed vernacular comes from, non-Black people usually struggle to find the answer.

The mixing of Kreyòl within the French language was to be expected with the prevalence of the Haitian community in Montreal. I just never expected it to be so widespread yet so estranged from its origin. At the end of the day, Kreyòl is not a slang from Montreal , nor is it considered to be a part of Quebec patrimony. Similarly, Ebonics or African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) is frequently mistaken as internet slang. This mindless habit simultaneously ignores the ballroom origin of the language and the struggle of the people who birthed it out of resilience.

The Linguistic Society of America asserts that “the term [AAVE] was created in 1973 by a group of black scholars who disliked the negative connotations of terms like 'Nonstandard Negro English' that had been coined in the 1960s when the first modern large-scale linguistic studies of African American speech-communities began”. Therefore, historically, this adaptation of language has been downplayed as inappropriate for "standard" society and disregarded as unworthy of acknowledgment. But AAVE, just like Kreyòl, was born out of colonial necessity.

In my experience, non-Black people borrow from this vernacular to add comedic effect to their speech;it serves as a way to relate to experiences of blackness, without having to endure its embodied consequences. It is completely natural to want to relate to each other, however,this should not be done by mimicking a core part of black resilience.

This is a contentious topic that Samantha Chery’s article “Black English Is Being Misidentified as Gen Z Lingo, Speakers Say” addresses. Chery highlights the experience of Kyla Jené Lacy, who identified AAVE as being a refuge. It is clear from this article that Lacy gets validation from attending a predominantly Black college later in life. In this particular setting, she is able to use AAVE , without fear of having her intelligence undermined without the need for code switching— a way to appease white discomforts towards blackness through speech.

I can recall a phone interview I had for a job where I code switched.When they saw me in person, they were stunned that I was Black and able to “speak so eloquently”. Throughout the meeting, I kept getting remarks on how impressed they were that I nailed my French test. There was always an incentive to emphasize that my ability to tame tints of my blackness through language made me better than other Black people who didn’t. For Chery “AAVE serves as communication among people with a common culture.” This is what Kreyòl is for me; this usurping of language is as prevalent in English as it is in French.

In Quebec, the creators of this conjunction of languages are actually Haitian kids who have developed a method of adaptation to a Quebecois culture that has alienated them. In this optic, when white people use this dialect without awareness, resilience is distorted as something "fun" for them to mock and fetishize. Rendering Black forms of linguistic adaptation the center of comedic relief. Perrye-Delphine Séraphin’s article titled Créole 101 testifies that this can feel like mockery: “I always felt like it was to ridicule my culture of origin and it insulted me a lot ” stated Séraphin.For me, the feeling she is describing, is insidious. It makes my ability to experience my Haitian identity challenging to come to terms with.

Chery’s article extends the sentiment that there is an incessant narrative of comedy attributed to AAVE by non-Black people. According to Chery, “These non-Black people speak it as a form of entertainment, giving them a Black caricature in a way, kind of like a minstrel show”. In essence, creating a form of linguistic blackface. For reference, minstrelsy was racist theater. They were performances by white actors in blackface specifically made to caricaturize and mock Black people.The danger here is that some may tend to internalize that comic relief role as their place in society, instead of the continued demonstrations of resilience it is. I was foolish enough to think we could have avoided this linguistic blackface , but here we are.

The blatant erasure of the Black origins of Kreyòl, is hurtful for many reasons. One of my first philosophy teachers told our class: “If it wasn’t for the Haitian nurses in Montreal, there would be no working healthcare system.” Haitians began to migrate to Quebec in 1963. It was encouraged by the Canadian need for labour. The West Indian Domestic Scheme is a great example of the institutionalization of Caribbean identity to profit off of and exploit Black bodies. We still benefit from this Black labor today.

Although Haitian influence in Montreal is undeniable through the history of its institutionalization, we cannot omit the circumstances that have forced Haitians to demonstrate resilient qualities as they arrived here.This generational resilience goes all the way back to the Haitian Revolution of 1804 and has only endured since.The mixing of languages, especially for young people, is very much a part of that.

I struggle to understand how practices of adaptation become trendy. While white people want to be oppressed in order to win the oppression olympics’ , Black people still have to work double-time to counter its effects. The negative underlying perception attributed to the vernacular is exemplified in the La Presse article by Amin Guidara, Le Nouveau Joual de La Métropole which–despite its attempt to contextualize linguistic integration–states that this assimilated language is a: “gibberish-like slang.” To me, this is a reduction of the complexities of integrating Kreyòl—a language which is often devalued as a dialect—into an established Quebecois French, which carries its estate by racist threads.

The mixing of Kreyòl with French is seen as a downgrade of the French language for supporters of Bill 101—the people concerned with the decline of French language. As a result, we code switch when we face the reality that our natural ways of expressing ourselves are political. We are aware that we will be judged and discriminated against for the resiliency of our speech because it fails to lean into a code that does not fit Quebecois puritan standards. I am very well aware that some white folks have lived in predominantly Black neighborhoods in Montreal and have “talked like this their whole life”. In spite of this, they are not subject to the same gaze as Black people are when using the vernacular. Additionally, their whiteness may provide them with additional protection from the judgment often associated with the use of Kreyòl in French.

Black joy endures the process of integration. In order to experience that state, we have to first undergo the labour of building resilience. That is something that needs to be acknowledged when speaking Kreyòl.

This is not to say that I think non-Black people should be forbidden from using any of this mixing of language; at this point, Haitian influence is ingrained. It is pointless to try and dictate how people should speak. However, I do believe that a more productive course of action involves having conversations on ways to honor the Haitian origins embedded in Quebec History and avoiding using Kreyòl as a punchline.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 13, published March 7, 2023.