‘We Want Them All’: Syria’s Detained and Forcibly Disappeared

Twelve Years Since the Syrian Civil War Began, Families Are Still Looking for Those Taken by Bashar Al Assad’s Government

The posts on Yara Sabri’s Facebook profile are not the kind one would expect to find on the page of an actress.

A post from Oct. 24, 2022, reads in Arabic, "We want to know the fate of the detained and forcibly disappeared: Ahmad Bakdounis _ Khalil Maatouk _ Rama al Osos _ Samih Bahra _ Bassam Bahra _ Abd al Aziz al Khayyir _ Iyas Ayyash _ Maher Tahhan. #wewantthem_wewantthemall."

As far back as 2011, post after post on Sabri’s page catalogue the names and photographs of Syrian citizens, most of them men, but with a few women and children included.

In each post, Sabri seeks the whereabouts and calls for the release of those believed to have been kidnapped by Bashar Al Assad’s government since the start of the Syrian Civil War.

When protests first began in Syria in March 2011, Sabri was a celebrated actress with a decades-long career. Fellow Syrians would recall her notable roles in Arab television series like Four Seasons (1999), The Palestinian Alienation (2004), and The Wait (2006). She would later star in the Canadian film Peace by Chocolate (2021).

Sabri was living in Damascus with her husband and two children when Assad’s government began stomping out protests in the capital.

"I saw with my own eyes what was happening,” Sabri told The Link, speaking in Arabic. “They were entering my neighbours’ houses and killing people.”

Violent suppressions were a response to what began as peaceful uprisings. The Arab Spring, a wave of anti-government protests that had been sweeping the Middle East and Northern Africa in 2011, had spurred existing dissatisfaction with Assad’s rule. Syrian protestors were calling for Assad to step down, chanting, “the people want to bring down the regime,” a popular slogan during the Arab Spring.

Over the following years, the conflict culminated in a complex civil war that would last over a decade. Today, its results are more than evident. In 2021, the total number of Syrian refugees stood at 6.8 million, constituting the largest refugee group in the world.

Yet this isn't the only way Syria has been emptied.

Since 2011, the Assad government has been detaining tens of thousands of citizens, imprisoning and torturing them in detention centres like the notorious Saydnaya Prison.

Some were detained and later released with clear arrest warrants. Many others, however, had disappeared without warning—from government checkpoints, from their workplaces, their universities.

In March 2022, the New York Times reported on two suspected mass burial sites near Damascus where the bodies of detainees are believed to have been dumped hundreds at a time in unmarked graves.

"There are many people who the regime denies were taken,” said Sabri. “They kidnap them and there is no record of arrest, nothing.”

These individuals were taken by the dreaded mukhabarat, the Syrian secret police, and remain missing until this day. They are Syria’s forcibly disappeared, and their families are still searching for them.

'Walls Have Ears'

Stories of the mukhabarat and of torture prisons are a constant in the Syrian consciousness. And much like a scary bedtime story, they serve as a warning.

The United Nations stated that government arrests in Syria “have been deliberately instrumentalized to instil fear and suppress dissent among the civilian population.”

“Walls have ears,” said Eiad Herera, describing the climate of vigilance in Syria. He arrived in Canada as a refugee in 2014. “Even in your home, don’t talk politics.”

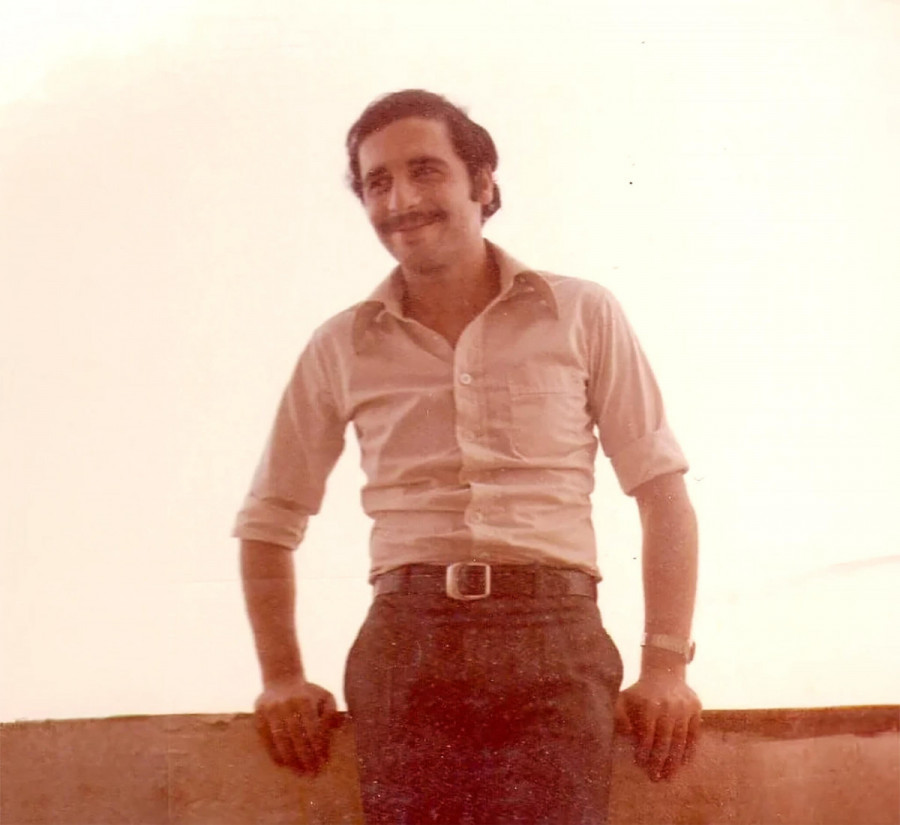

The activities of the mukhabarat extend to the days of Assad’s father, Hafez al Assad, who ruled from 1971 until his death in 2000. Ragheed Al Tatari, a former air force pilot in Syria, was imprisoned without trial by Syrian authorities in 1981. Al Tatari is still imprisoned, the reasons for his arrest a mystery. Human advocacy group The Syria Campaign believes him to be the country’s longest serving political prisoner.

His son, Waill Tatari, born a few months before his arrest, now resides in Calgary. He left Syria in 2013 and arrived in Canada as a refugee in 2019. Tatari is in contact with his father via a lawyer who visits him in prison from time to time.

“It’s really hard to describe,” Tatari said about how it felt leaving his father behind. “Because you feel like there is a part of you there. And there is nothing you can do about it. I was powerless, and then I had to leave.”

The mukhabarat’s activities intensified in 2011.

As those around Sabri paid the government’s bloody price for dissent, her opposition to the regime and unique position as an influential public figure naturally led her down the path of activism. She transformed her Facebook profile from a simple social media account to a public record of the detained and forcibly disappeared.

Anyone whose family member was taken could send the actress a personal message with the victims’ name, occupation, photograph, and the date and location they were last seen.

“[Sabri] is one piece of that big puzzle of human rights defenders in Syria,” said Herera. “Since the beginning, she was active. She still is.”

Sabri's effort isn’t the only one of its kind: many other Facebook groups with the same mission exist. Some of these groups assisted in identifying scores of dead, unnamed individuals in the infamous Caesar photographs, a series of graphic images leaked out of Syrian prisons by a former forensic photographer for the Syrian Military Police in 2014. The photos exhibited clear signs of starvation and torture in at least 6,786 prisoners who had died in government custody.

In an article published in August 2020, Reuters quoted Assad as calling these photos "allegations without evidence."

After immigrating to Canada as a refugee in 2018, Sabri would continue this work while in Montreal. The contents of her page are what forced her to claim asylum in the first place.

Between 2011 and 2012, the Syrian government repeatedly demanded she shut down her page. They threatened her and her children’s safety and they blacklisted her in the entertainment industry.

"The result was a war against me and my family,” Sabri said about the response. “And I wasn't prepared to change my humanitarian stance in exchange for the government's good favour.”

In 2012, Sabri and her family left for the United Arab Emirates. The last straw came when they were blacklisted from renewing their Syrian passports, and with nowhere to turn, they sought refuge in Montreal.

Sabri bitterly admitted that if she were someone else, the result would have been completely different. Assad’s government hadn’t caused her substantial harm so as not to further incite the public against them.

"If I was a normal person, it's possible that right now my parents wouldn't know where I am," said Sabri.

A “Thorny” Topic

Saleem, a former executive of the Concordia Syrian Students’ Association (SSA) whose name was changed for his safety, recalled an incident that echoes Sabri’s risk.

Before his arrival in Canada as a refugee in 2015, Saleem had attended a Syrian university where another student was arrested in the middle of a lecture. The student had criticized the regime in a Facebook post the day before.

“He was taken in front of his friends by law enforcement and he never came back,” said Saleem in an interview with The Link. “Then they told his parents that he was dead.”

The topic of Syria’s detained and forcibly disappeared is a “thorny” one in the Syrian community, according to Saleem. Although he freely discusses the civil war and the government’s arrests with his friends in private, he can’t do so publicly. Even living in Montreal, many Syrians avoid criticising the Assad government too openly in fear of reprisals if they were ever to return.

There is also another concern Saleem had during his days as an SSA executive. The student association had collectively decided not to discuss the crimes of the Syrian government so as not to provoke infighting between anti-regime and pro-regime students. Many individuals who are pro-regime deny any wrongdoing on the government’s part, Herera and Saleem said.

“If [the SSA] would take any political side, then immediately, we're alienating all the other parties, which is not something that we wanted to do,” said Saleem. “We want people to unify, not to divide, and what unifies us is our culture. What divides us is politics, so we stay away from that.”

The decision went both ways: the SSA does not publicly condemn Syria’s opposition either. The Syrian opposition comprises numerous groups across the country that are against Assad for various reasons. Opposition groups can also be in conflict with one another.

“From everybody's point of view, the other party is a criminal,” said Saleem. Both Herera and Saleem acknowledge and vehemently denounce the crimes of the Assad regime, but they also point a finger at Syria’s opposition groups.

“[Assad’s government] did despicable things. But they were not the only party who kidnapped people,” said Saleem. “There are people who got hurt by both sides in very ugly ways.”

In 2015, Herera’s uncle was kidnapped for ransom from the province of Sweida by an opposition militia group. When his family said they had nothing to give them, the militia freed him a month later.

A more publicised case is that of Syrian rights activist Razan Zaitouneh. A staunch advocate for political prisoners herself, Zaitouneh would later spearhead many anti-regime efforts and become a key figure of Syria’s early uprisings.

Fearing the onset of government arrests in Damascus, Zaitouneh escaped to rebel-held Douma in 2013. While there, she began documenting the abuses of the Army of Islam, an opposition group that governed the city. Zaitouneh was later kidnapped from her Douma office. Her fate is still unclear. Years later, several clues point to the Army of Islam as the culprit, and she is thought to have died in their custody.

Sabri condemns the Assad regime, but doesn’t align herself with any opposition groups. She explained that the risks she took weren’t rooted in any self-interest.

“For me, it's about human beings—the country is its human beings,” said Sabri. “When I took that stance, I took it for the people, the country, not for myself.”

A Need for Solidarity

Tatari finds the silence surrounding the Syrian government’s human rights abuses shocking. He believes that Syrians shouldn’t avoid difficult topics in fear of offending others.

“Come on, my dad is in jail for 42 years,” said Tatari. “Someone’s going to feel bad about hearing his story? It’s a bit insulting.”

Tatari agreed that unity should be preserved in the Syrian diaspora, but he believes a lack of public discourse can be an obstacle to helping those like his father.

He stressed the importance of open conversation within the community. “People need to learn to live together, but they also need to learn the truth,” said Tatari.

Political alliances had also featured in the aftermath of the earthquakes that devastated parts of Syria in February 2023.

Herera recalled how some Syrians avoided donations to humanitarian groups operating in regions controlled by the other side. While he said it is normal for people to disagree politically, he believed a line should be drawn at human rights.

“[Syrians are] lacking social solidarity,” said Herera. “We need more.”

Over the last 12 years, the issue of Syria’s detained and forcibly disappeared was brought to the attention of non-governmental organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. But Herera and Tatari said more should be done by the international community.

Tatari is trying to spread the word about his father in hopes that international pressure on the Syrian government would get him out. On Nov. 18, 2022, Sabri called for Al Tatari’s freedom on her page.

“I’m sure I’m going to see him again,” said Tatari.

Far and few in between, there are posts on Sabri’s page in which she celebrates detainees who were released, congratulating them each by name. Attached to the posts are images of Sabri’s “Freedom Bus,” a rough sketch of a vehicle that is carrying released detainees back home. A group of stick figures is lodged inside, poking out of its windows, smiling, and carrying signs that say, “We want them, we want them all, we want freedom.”

_900_524_90.jpg)

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)