What It’s Like to Be an Illustrator Ahead of Expozine

Artists Zoe Maeve Jenkins and Graeme Adams Reveal Their Process

Every year since its inception in 2002, Montreal’s small press, zine, and comic making communities convene at Expozine, North America’s largest small press fair.

Expozine happens every November, this year on the weekend of the 25 and 26. Many of the exhibitors are Montrealers, but the fair attracts people from all over North America and Europe.

Zoe Maeve Jenkins, 24, and Graeme Adams, 25, are a pair of artist friends hoping for another chance to display their respective works at Expozine this year. Adams was The Link’s copy editor and graphics editor between 2013 and 2015.

They plan to share a table.

“Often they don’t tell you until it’s quite late,” Jenkins said. Both agree that they find the selection process of who gets awarded a table at Expozine mysterious. However, Jenkins said sharing tables is a fairly common practice, which helps negate the sting of rejection.

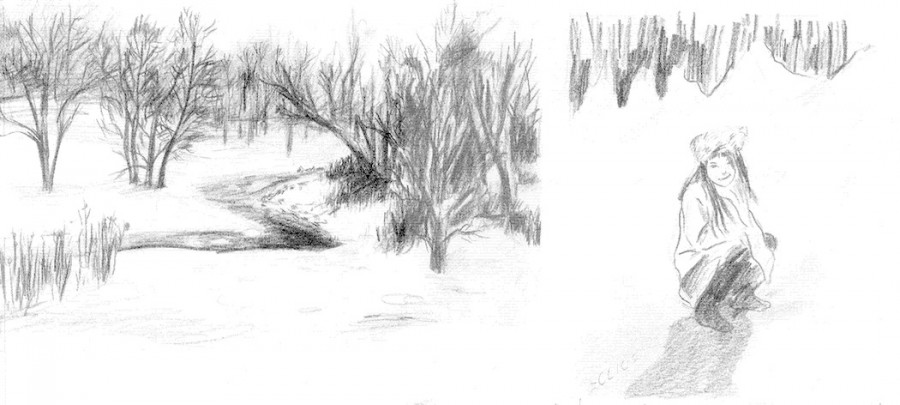

Jenkins and Adams have collaborated on a comic called “Low Flying Star”, and are about to begin its second instalment. Each artist’s work starts on opposing sides of the comic and join in the middle.

Last April, Jenkins graduated from Concordia’s Fine Arts program with a degree in studio arts. Imagine what Anne of Green Gables would look like if she were an art student living in

Montreal in 2017, instead of Prince Edward Island at the turn of the 20th century. Jenkins’ memory doesn’t include a time when she wasn’t drawing.

She first went to Expozine as a visitor five years ago when Montreal was brand new to the Toronto native.

During the first few years of her degree, Jenkins focused on making large scale paintings, but in 2014 after attending Expozine and a handful of other fairs like it she began to experiment with book based works of her own.

With more applicants than tables, applying for Expozine can seem daunting. But Jenkins applied to exhibit her work at Expozine two or three years ago and was accepted on her first try. Even though she only had one comic to present that year, the budding zine artist felt welcomed.

While two days of making small talk at Expozine can be tiring, the work pays off when she finds herself energized and inspired to create new things.

Zines, products of punk/DIY culture, are more likely to be reproduced using a photocopier than professional printers, the way comics are. Zines don’t necessarily need to have panels or characters that tell a cohesive story the way a comic does. The self-published mini mags can be fictional or talk about real things, from grassroots mental health tips to where to find photobooths in Montreal metro stations.

According to Jenkins, another area of distinction is that zines are typically be small, sometimes pocket-sized works. Comics tend to be more or less standardized, when it comes to sizing.

Jenkins stressed how important zines are as physical works. “It tends to be better when read in person,” she said, not worrying to make her books available online.

Instead, she makes them available to be purchased in a physical copy, something she believes the average zine reader cares about. When Jenkins creates her zines she thinks about the layout in terms of the physical copy, and never about how it would appear if she posted it to the web.

She noted that there doesn’t seem to be any stigma against self publishing in the zine world, rather it’s the norm. Jenkins said, “It’s seen as a valuable thing to do.”

The process of making zines is laborious, perhaps more than other forms of art. Her first and longest zine took her a year to produce.

“I do think it’s good to work on things when you don’t feel like working on them because that is how you’ll end up actually getting stuff done.”

She likes the repetition of drawing and perfecting the same image over and over again. “I also enjoy being able to chip away at something and not always putting such active emotion into it.”

Jenkins explained that when she focused on painting it could lead to feelings of intense investment in the outcome of one piece. In contrast, the process of creating a zine feels calmer to her. She can logically look at her work and decide where each panel goes, then redecide and rearrange. And rearrange and redecide. To Jenkins, zines are about “making small pieces come together into something larger.”

Living in Montreal for the past five years has influenced her artwork, especially the landscape of the city in contrast to her hometown of Toronto. While she wouldn’t call herself a perfectionist, there are certain areas of her work where she’s very particular, such as wanting the pages, “to be really really crisp.”

“I don’t like making comics where I’ve written something and then have to have an image to illustrate it. I’m much more interested in how those things fit into being one thing, and how they create gaps or connections that I wouldn’t find otherwise just working in one medium or the other,” — Zoe Maeve Jenkins

Jenkins uses a mix of India ink, 2b, and coloured pencils, as she finds it difficult to use the same materials all the way through. Once, a classmate commented that the way a series of her drawings flowed when presented as a whole reminded them of written poetry.

She understands how fussy the process of creation can be, and has learned when to step back and declare that she’s done. When making a zine, Jenkins starts with the prose she wants to use.

“It never feels fully integrated to me until it’s completed with pictures.” She views it as the most intuitive way to fill in the questions the text poses.

Jenkins collaborated with her friend Sasha Tate-Howarth, a poet, to create a zine entitled “Memos.” She made the drawings and Tate-Howarth wrote the words. They viewed the individual nature of their work as being complementary.

The cover of “Memos” looks like a moving mass of wavy, crystallized ocean. Jenkins explained that rubbing salt into the ink created a dimensional texture. She likes to try different things and said her most recent drawings are line heavy, using a combination of pen and pencil.

“I don’t like making comics where I’ve written something and then have to have an image to illustrate it. I’m much more interested in how those things fit into being one thing, and how they create gaps or connections that I wouldn’t find otherwise just working in one medium or the other,” Jenkins said.

She’s arrived at a point artistically where she does not want to have one without the other. Along with a number of former Concordia arts graduates, Jenkins contributed to a comic anthology organized by former Concordia student Jordan Beaulieu, intended to come out shortly before Expozine this year.

She collects other material as research and inspiration. Her drawings are incredibly textured.

Learning how to choose the right shade so that it would appear as dark as she wanted was a learning curve, but one she quickly got the hang of. Jenkins usually prints her zines in black and white because it’s considerably cheaper.

“There are a lot of artists working in the same medium as me, but the things that inspire me often come from outside of my medium,” Jenkins said.

She mentioned “reading a lot of everything,” as an inspiration for her work. As an example, she tries to integrate certain academic theories into her art.

Meanwhile, her friend and fellow artist, Graeme Adams, started drawing at the age of five. It quickly and permanently became an integral part of his identity. He eventually pursued an education in the Fine Arts program at Concordia. He graduated in 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in studio arts.

“I work at a restaurant with a couple of small gigs on the side. I think I live a pretty typical millennial life in a lot of ways,” Adams said.

For Adams, making zines is a lengthy, emotional process that forces you to reckon with your own limitations. It’s a “totally isolating process” that only he can complete alone. Since creating comics takes him a while, he can only create a substantial amount of work by spending time by himself.

Consequently, he can go long periods of time without talking to anyone and often ends up “sitting in front of a table stewing in frustration and confusion.” It may not be the most healthy lifestyle, but he’s gotten used to it nonetheless. Perhaps making art gives him a sense of control that he feels is lacking elsewhere in his life, he pondered.

Comic-making is as a way of “Energizing the planes of life we all occupy, but that it doesn’t have any spatial or temporal presence, like the mental life, emotional life, spiritual life,” Adams mused. Like Jenkins, he gets inspiration from reading, but also by simply from the world he’s living in.

“If making one drawing is like walking a tightrope, making a comic is like walking a tightrope while juggling,” he said.

Part of why Adams views it as more difficult is that an individual drawing must only speak for itself, whereas a theme has to be continued throughout a comic.

Adams wants each drawing to stand on its own as an individual work of art, while also forming aesthetic coherence with the whole comic. A consistent visual connection must be maintained through a line of narrative and action. He thinks comics are an unwieldy art form that, if done correctly, provides him with a stronger sense of satisfaction.

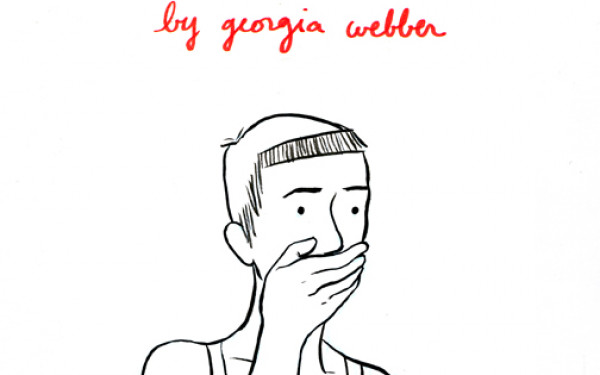

Adams suffers from what he describes as a common problem for artists that, “They end up hating their work weeks, days or even hours after they’ve made it.” He explained that even though he ended up really disliking the drawings he made in a comic entitled Spells a few years ago, the extra positive response he received from readers helped to make it worth the distress he put into making it.

His work jumps between different styles of drawing. It might not be the best idea in terms of self branding, but he finds drawing to be so interesting that it feels limiting to create his comics in one style.

“I think life tends to be full of uncomfortable syntheses of moods, so having goofiness and bleakness in close proximity is kind of an ongoing goal for my drawing,” Adams said.

He admitted that in many respects he’s still a beginner, which means that every drawing he makes still has the thrill of being novel and exciting. His comics vary in tone, some being serious and gloomy and others being silly and irreverent.

“I think I’m a pretty serious person who has trouble lightening up, so the sillier drawings are a way of challenging myself to do that,” he continued.

“But there’s often a serious intent behind them too, to the extent that they provide contrast with the gloomier material. I see Expozine as a mass expression of solidarity among people who toil over their creative projects, instead of doing more pragmatic things. It gets hot, crowded and smelly, but at the same time it’s totally exhilarating.”

1_900_600_90.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)