Technology Is the Key to Self-Actualisation

In our future vernacular, “career” and “job” will become synonymous.

This shift in language may seem distantly utopian, but technology will rapidly narrow the gap.

What’s so bad about a job? The answer lies in the origins of the industrial economy.

A job is something we endure for 40-plus hours a week to earn a wage. This idea originated during the industrialization of the 18th-century, when the word “job” was used by factory workers to describe demeaning wage work. Indignant about being driven from their traditional work on the land or in crafts, workers ascribed “job” to factory labour to express their revulsion.

The foundation of this house of cards begins with Adam Smith’s belief that people are naturally lazy and will only work for pay. In his 1776 work The Wealth of Nations, Smith writes “It is the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can.” Despite this, Smith recognized that employees would be in dire straits. He argued that work forces the worker to sacrifice “his tranquility, his freedom, and his happiness.”

A century later, this idea initiated the theory of scientific management. The result was a manufacturing system that reduced the need for skill and meticulous attention by workers, instead opting for assembly-lines and repetition in the name of efficiency.

Since then, work has been a mere money-making, GDP-generating, chore-like exertion. The remnants of this history continues to shape our world today.

In his 2013 article “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs,” anthropologist David Graeber notes an important prediction by John Maynard Keynes. Keynes forecasted that by the end of the century, technology would advance enough to reduce workloads down to 15-hour weeks. Obviously, this hasn’t happened. But, why?

Graeber argues that technology marshalled us to work even more. And so, society can afford more bullshit jobs because our robots are getting better. This is what he calls the paradox of progress—the richer we become, the more we can afford to waste our time.

In my view, Graeber underestimates the potential for technology to transform the meaning of work.

Technology is not to blame for meaningless work. In reality, technology is our friend—it is consumerism that is our foe.

Of course, there is some hypocrisy in that statement. Much of our modern technology was developed because we wanted, and could afford, to consume more. But, that’s beside the point. Pondering which sequence of ideas led to the creation of modern technology doesn’t really matter, pragmatically speaking. What does matter is that we have it.

What we need to be asking is “now what?” How can technology help us find more meaning in our work?

Technological advancements, such as automation and artificial intelligence will free up more of our time. Contrary to the myth, automation will not mean the death of all human jobs: it will mean the death of unfulfilling jobs.

In 2013, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne analyzed 702 American occupations for the likelihood of becoming automated. They found that 47 per cent of American workers were at high risk of being replaced by robots.

Interestingly, these jobs were not clustered on the basis of manual labour or clerical work. Despite the colour of workers’ collars, the critical factor in determining the vulnerability to automation was whether or not the work involved a predictable routine.

Some examples include jobs in transport, logistics, office support, and sales and services, which are spread across occupational prestige. In fact, the Stanford academic and author Jerry Kaplan claims that automation is “blind to the colour of your collar.”

In my view, the concerns over robots taking over our jobs is largely unwarranted.

During the Industrial Revolution, textile workers protested machines and steam engines for stealing their livelihoods. What eventually followed however, were more jobs. Economist James Bessen reported that in 19th-century America, the amount of coarse cloth a weaver could produce increased by a factor of 50, and the amount of labour required dropped by 98 per cent. As a result, price per yard of cloth dropped, demand increased, and more weaving jobs were created. In fact, Bessen reported that the number of weavers quadrupled between 1830 and 1900.

Jobs for everyone will increase in the long-run despite the short-term disruption. Just as the Internet democratized information and allowed many to gain mastery over fields they had little formal training in, automation and machine learning will alleviate the burden of working menial jobs. This will open up a new world of endless possibilites.

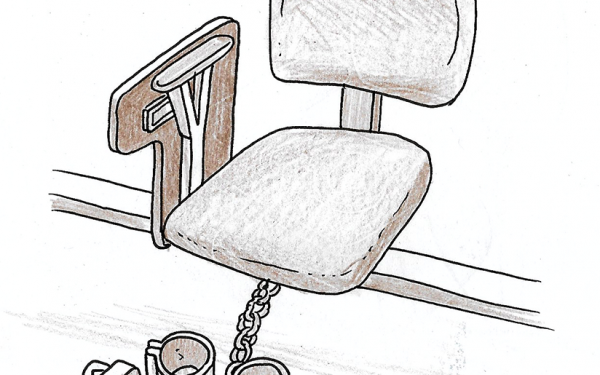

The future of technology will enable us to reach self-actualization, or at least get closer than we’ve done in the past. Without the bounds of wage blackmail, we don’t have to pay for our own corporate enslavement. We don’t need to sell our soul to the engine of extraction. We ought to save it for ourselves. It will pay huge dividends. Time will tell.

_600_832_s.png)