Space Concordia delays satellite launch until 2022

One small step for mankind, one giant leap for student aerospace—COVID-19 notwithstanding

Space Concordia’s plans to launch a satellite into space have been postponed until 2022, according to Kimberly Rutherford, project manager for the satellite mission.

Terrestrial concerns—like the global health crisis—have taken the forefront and decelerated the satellite building process. With COVID-19 looming since the beginning of the year, design review meetings essential to getting the satellite approved have been pushed back, she added.

And thus, so have the group’s ambitions for interstellar exploration—momentarily, at least.

It was in 2018 when the prospect of an actual mission in space became viable for engineering and computer science students at Concordia.

“Since 2010, we’ve been in two-year-long competitions to build satellites and we ranked consistently in the contest’s top three list,” said Rutherford. Their reliable performance was part of what helped them get noticed as candidates for the grant, she added.

The initiative was part of the Canadian CubeSat Project, at the time a new rollout by the Canadian Space Agency. Post-secondary students were invited to submit proposals for satellite space missions with a chance to receive funding.

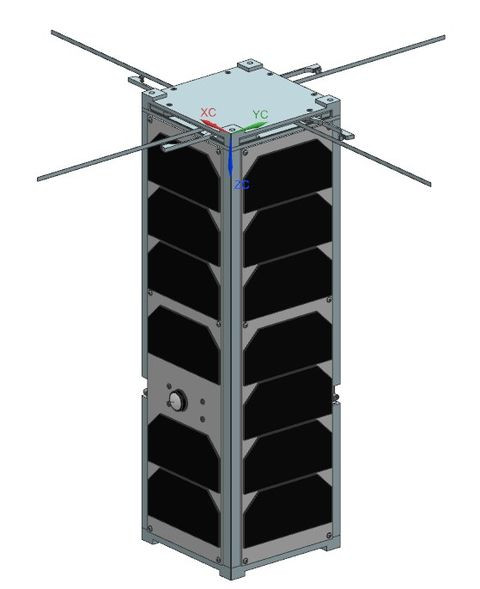

The CubeSat is a miniature satellite with a size of 10 cm x 10 cm x 10 cm cubic units—small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. The compact design means it is less expensive to launch and is ideal for student space missions. Rigorous testing in a controlled environment is required beforehand to ensure that the device can survive the rapidly-changing atmosphere of outer space.

Concordia was one of 15 institutions across Canada selected to be part of the project, receiving $200,000 in financial aid.

Space Concordia’s proposal for space travel included satellite imaging that would provide data on dust measurements and the effect of climate change on coastal regions in Argentina and Namibia, said Rutherford.

“There’s a camera that will be able to take specific pictures of those areas, and we’re gonna give them to climate scientists at the University of Montreal,” Rutherford said. “We’ll be able to take pictures for one year. That’s how much a CubeSat of our size can survive in space.”

This period of time is only for Space Concordia's CubeSat and is not necessarily the standard for all of that size.

“The primary objective of the Canadian CubeSat Project is to train the next generation workforce for the space sector,” said Audrey Barbier, a spokesperson from the Canadian Space Agency. “By guiding the students through a rigorous process of designing, building, testing and operating a satellite, the Canadian Space Agency believes these students will gain the essential skills needed to be successful in space or aerospace industries.”

“It’s so important for all the alumni and everyone that has worked on the previous CubeSats. Everyone had the dream for Space Concordia to bring something to space and it’s happening,”

— Kimberly Rutherford

The advent of the CCP marked a celebratory moment for the department, as Space Concordia members had been vying for a way to make their space travel dreams come true for over a decade. But the exorbitant costs of space travel meant such endeavours were impossible until they were allotted larger grants.

“It’s so important for all the alumni and everyone that has worked on the previous CubeSats. Everyone had the dream for Space Concordia to bring something to space and it’s happening,” said Rutherford. “I remember when we learned that we won the CCP grant, people were yelling, ‘Wow!’ Maybe for the future, it’s going to bring more interest to the space sector.”

Rutherford said the group is preparing for a critical design review in March 2021.

“By March, our satellite design needs to be finished, everything needs to be functional,” she said. “We need to have built something to prove that everything’s going to fit together, all the analysis simulations also need to be completed.”

Fortunately, the group has been able to work through the design phase even without full lab access. The systems teams—which handle different parts of the design process for the satellite, such as electrical engineering and programming—meet weekly via Zoom as needed.

“We’re building an engineering model [for March], so it's not the final product,” said Rutherford. The model will be built with items from the lab and a 3D printer at a designated teammate’s home, given the current pandemic restrictions and that the prototype doesn’t need a controlled environment.

“But after that, after the big review, we do need to have a specific environment, a ‘clean room.’ Because we don’t want to contaminate [certain] components. In space, contamination can be quite problematic,” she said, mentioning changing temperatures and varying electromagnetic conditions.

For now, the team remains undeterred to make their wildest dreams a reality. If all goes well, the final assembly process will take place in September 2021.

“It’s going to be crazy to actually internalize that moment where something that I’ve built with my own hands is going to space—going to be able to take pictures, in space, of Earth,” added Mario Sanchez, systems engineering lead at Space Concordia.

Sanchez grew up watching movies set in the intergalactic, and could never have fathomed that one day he would have the opportunity to create a satellite that would be launched into orbit.

“I’ve dreamt of that moment when the satellite—not even the moment that the rocket is going up, but just the moment of driving up to the launch station,” said Sanchez. “Because at that moment, everything that I worked towards will have been met, and we’ll just be cruising on to this station where this satellite that I helped build, will be launched.”