Racism, the Canadian Way

McGill Panel Explores Canada’s Relationship to Slavery

Canada’s relationship to slavery dates back to the 17th century and it’s its own problem—not part of the United States’.

To confront Canada’s not-so-rosy history of how it treats “the other,” it needs to start telling it, panelists said at a talk at McGill Monday night organized by the university’s Black Students’ Network.

“I have yet to encounter the Canadian student who comes into that class, knowing that slavery happened in Canada,” Charmaine Nelson, associate professor of art history at McGill, said of one of the courses she teaches.

The talk, held in the Students’ Society of McGill University Ballroom on McTavish Street, also featured St. Mary’s University assistant professor Darryl Leroux, author and historian Frank Mackey, and PhD candidate Rachel Zellars, who acted as moderator.

Much of Canada’s Black history is not in education curriculums before university. And even at the postsecondary level, there is little space taken in Canadian academia on the subject, Nelson said. In Canada, there are no university programs that deal directly with African heritage. In contrast, such programs are available at nearly every university in the United States, she said.

That lack is represented in universities’ faculties as well, she added, pointing to the fact that she is the only Black art historian in Canada. She admitted to the pressure she feels as a result.

“I constantly feel isolated at McGill. This is not a safe space for me,” she said. Indeed, the Canadian academic landscape has diminished in diversity over the past several years, Leroux chimed in.

Called “Discourses of Race: The United States, Canada and Transnational Anti-Blackness,” the event originally had The Atlantic author Ta-Nehisi Coates as its headliner, but the writer couldn’t make it, and is to speak at McGill on March 2 instead. Coates was slated to discuss his essay and The Atlantic’s June 2014 cover story, “The Case for Reparations,” in which he discusses the States’ federal policies that created the deliberate discrimination and segregation of African Americans.

Monday night’s talk echoed an intimate discussion held in Concordia’s SCPA building on Mackay Street days before, when a small group of students gathered to watch “Journey to Justice,” a 2000 National Film Board film about a group of Canadians who challenged the country’s racism.

The group, hosted by Concordia student Aminka Belvitt on Friday evening, pointed to the lack of openness about race in Canada.

“It’s passive,” Belvitt said, also pointing to the lack of media coverage of Montreal’s Black communities outside of Black History Month.

Dwight Best, Concordia graduate and founder of the African and Caribbean Students’ Network of Canada, was at the movie’s screening at Concordia Friday as well as Monday night’s panel at McGill.

He says that like it or not, the four February weeks dedicated to Black history are a tool for awareness.

“Canada has a lot of work to do,” he told The Link after Monday’s talk. “I think we’re really doing ourselves a disservice by not talking about how Canada came to be. There’s a lot of myth, there’s a lot of hampering the historical reality with what we would like it to be and that has been engineered.

“I think it’s important that we have a more honest, a more mature understanding of who we are,” he added.

Canada’s reticence toward discussing its racial history has also been institutionalized, the three panelists agreed Monday. In Quebec, focus is directed at language and the oppression of francophones under British rule, which results in it its problematic relationship with race being overlooked.

“A lot less attention needs to be paid to language and much more to race,” Leroux said.

He dispelled a common myth that every Quebecois has Aboriginal blood in them. Records show that only 13 First Nations women married settlers, he countered.

“This is the logic of francophone racism in Quebec—that they don’t have to talk about indigenous rights and indigenous land claims because they somehow are ‘pure laine’,” Nelson added to Leroux, citing the common trope used by Quebecers, which refers to exclusively French settler ancestry and conflicts with the false notion of widespread Aboriginal ancestry.

In fact, there were many liaisons between French and Irish settlers in the New France that predates Canada and Quebec.

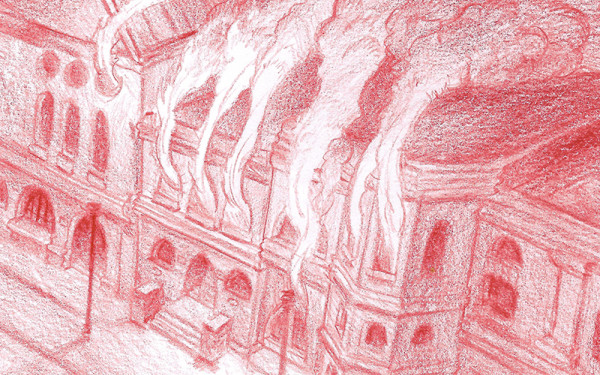

The panelists also addressed the province’s several incidences of public figures and spaces’ – Mario Jean, Radio-Canada’s Bye Bye and recently, Théâtre du Rideau Vert – use of blackface, which have been widely condemned.

“Why is blackface persistent here in Quebec?” Zellars, who wrote an opinion piece for the Toronto Star on the subject, said.

She pointed to theatre director Denise Filiatrault’s response to the Rideau Vert controversy, where an actor was painted in blackface to play Canadiens player P.K. Subban instead of simply hiring a Black actor. Zellars said Filiatrault’s defense that she was the first to hire a Black actor on Quebec television victimized herself instead of addressing the issue – a display of the province’s attitudes toward race.

“That wouldn’t happen at a theatre in Toronto,” Nelson said. “Because they know better.”

Canada’s slavery may have little to do with the whips and huts associated with that of the American South, but it was present. Slaves were smaller in number and proportion in Canada and lived in various parts of their owners’ homes, Mackey explained.

But the reasons why slavery didn’t transpire as it did in the States are mostly circumstantial, Leroux of St. Mary’s said.

“Slavery is coded as Black History—it’s not. It’s a global history,” said the professor, who linked Quebec’s history with that of Saint-Domingue, a French colony in the Caribbean, where “brutal” slavery was practiced.

The country may have eventually been a place of refuge for slaves from the States, but discrimination transpired and was legal for years to come.

Nelson explained that though Canada’s history with slavery may be labeled as “gentler” because it revolved less around intense manual labour, it was just as dehumanizing. Slaves were taken from the home they’d managed to create in places like Jamaica and the Caribbean, after being displaced from Africa, and put on yet another voyage, this time to Canada.

Because they were taken in small numbers to the British colony, they were often ripped from their families and communities, resulting in isolation, Nelson said.

“At the end of the day, the talking point is really about one’s humanity, that’s all that matters. The differences of brutality, ultimately in my mind, serve a purpose that helps white people much more than black bodies and Black people,” Zellars said, concluding the panel.

1_900_600_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)