Nothing’s Shocking

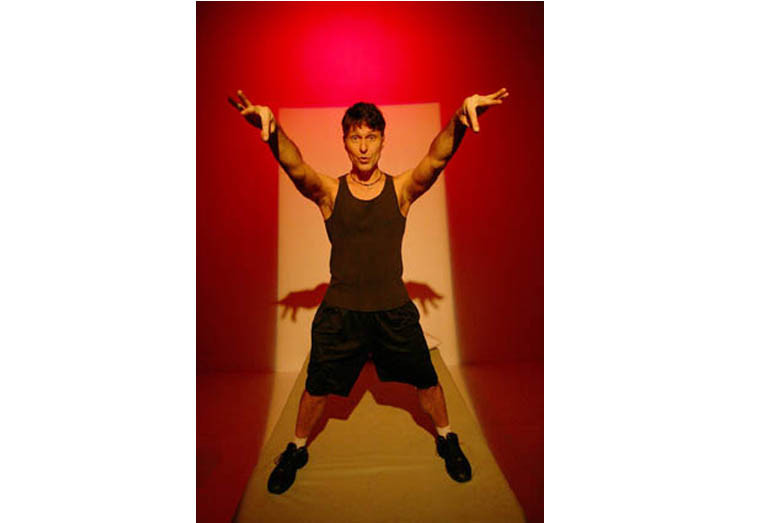

Tim Miller Brings his Special Brand of Performance Art to Concordia

Tim Miller is on the phone, and he’s boiling in more ways than one. Besides dealing with a California heat wave, he’s none too pleased with the results of the US’s midterm elections from the previous day.

“I feel very fraught this morning after our horrible elections,” he says from his Los Angeles home. “They were slightly less horrible than I thought they would be, but horrible nonetheless.”

While most left-leaning citizens might feel troubled by Congress’ shift to the right, Miller has a bit more of a vested interest than others. In 1990, his grant from the National Endowment of the Arts was revoked by the first Bush administration, kicking off an eight-year legal struggle that ended up in the Supreme Court.

That battle, which took place during a time when the American government was not acknowledging the growing AIDS epidemic, became symbolic for the effort of the queer community to gain acceptance in the mainstream.

Rather than toning his style down, his performance is as engaging and provocative as ever. He’ll be bringing his act to Concordia on Nov. 11 as part of the Lecture Series on HIV/AIDS.

On his performance style.

Some people can find it incredibly weird to be doing such extremely private, personal, and autobiographical material, though in these days of obsessive tweets and Facebook status updates, it would feel weirder when I started working as a young artist. Now it doesn’t seem so strange, since we’re revealing, telling constantly now, perhaps too much. I would actually rather we speak up, even though I’m not that interested to hear somebody tell me how much they love the doughnut they just bought, for example. [I try to promote a] space to reveal, rather than hide, speak up rather than suck up.

[About three years ago, I was performing at a college in North Carolina]. I was doing a piece full of really, really specific, totally dirty sex stuff. This was like [a] Baptist college, and I said “Oh, boy. Clearly, I won’t be invited back.” And I was feeling like this was really too much. But then I was so excited because after the piece, all these conservative, Republican Baptist kids were telling me that those really, really frank sex parts were what they most responded to because it gave them permission in their [own] work to get really honest, really specific. So, I try to remember that—those moments where you’re most freaking out, because maybe this is too much, could accidentally be the thing to be hitting at.

On the difference between activism and art.

I mostly think of myself as an artist, [but when I perform at schools] they’re bringing me as an artist to engage in social material. For a good dozen years, my creative life in the ’80s and ’90s, were kind of my formative period as an artist, as I was coming of age. I think in some ways that provided the template for the kind of performance I was doing around HIV/AIDS as a young man. I really saw the connection between [that and] what I do. Organizing a massive civil obedience in front of a federal building in Los Angeles is intimately connected to the performance I would do the week before to help get people to the event—help encourage people to do civil disobedience and get arrested, and then a year later, to be making a piece about a particular action. […] Our creative selves, our private selves and our public selves are in this big charged conversation with each other, and that’s true for artists frequently.

On how the AIDS crisis affected his art.

I was 21 years old in New York the first time I had to visit a boyfriend who was dying in a hospital. I work with a lot of college undergrads in that 18 to 22 year age [which is] the age I was when I was having to go watch my friends die and worry that I was next. That certainly is an enormous reality.

I had a boyfriend who was positive, and around ‘93, ‘94, people were figuring out, how do we relate? I felt it was really important to make a piece, being somebody who was negative, what was my experience being intimate and being in this relationship with this man, Andrew, who was positive. Nobody had made a piece about that yet. It wouldn’t be a piece we need to see now, and I don’t even perform sections of it now, because its [the issue is not] uncommon now. There’s been other cultural representations.

On optimism for America’s future.

Americans have to be optimistic or we’re banned! (laughs) It’s sort of the big sin, the slightly lunatic American optimism even when it’s completely without evidence.

The trend is obviously positive. I don’t know if I will live to see America grow to be as progressive as Canada. Probably not, the countries are different. On the other hand, I kind of have to nudge my Canadian friends and remind them that that you have Stephen Harper as prime minister, and we have Barack Obama, so the world moves in mysterious ways.

There’s no straight line of progress, certainly not in the US, where it tends to be not the question “Will we ever enter the 21st century?” but “Will we ever enter the 20th century?”

On Barack Obama.

I’ve been very critical of Obama, and I’m critical of him in my new show, and not just around the absence of any real progress on gay issues. You know, with these massive majorities, it’s very disheartening that in those two years, that he didn’t manage to do anything for gay people. It’s pretty fucked up. […] That said, now that we’re in a new situation, I’m sure it’s going to be easier to be a bit more supportive now that the Republicans have the House of Representatives.

My bottom line with him is that he’s been very disappointing in some ways, but he’s an enormously compelling, transformative figure. The US was the first western country to elect a person of colour as head of state. A hundred years from now it’s probably the only thing we’ll remember about his presidency. […] That we’re still kicking gay people out of the military is just insane and has become a really horrible symbol of how gay people are disrespected in the United States.

On his lawsuit against the US government.

It happened in 1990, which was a super formative moment in my life. I was coming into my authority as a performer, coming out of my 20s, feeling more confident.

It was also the year I tested HIV negative. After nine years of assuming I would die at any moment, it was like, “Hmm, maybe I’ll get to stick around.” It was a very charged moment, feeling very full of my voice and my citizenship and my creativity, I was incredibly involved internationally, [and] suddenly the government was messing with me. It was just one more of a feeling of being under attack. I used the same skills to draw attention to that, and to use my publicity moments, all this access to mainstream media I suddenly had, I was being interviewed to make my point about censorship and gay activism and AIDS activism. And in the US, the kind of attacks on artists were really linked to artists engaged in HIV/AIDS; some of the most powerful, confrontational work being done. How could you not engage HIV/AIDS? It was this giant, global plague. If you weren’t making work about AIDS in the late ’80s and ’90s, what were you making work about?

I spent eight years taking the case to the Supreme Court, which was emotional and complex and, strangely, I never made a piece about it, even though it was such an enormous chapter of my life. I didn’t want to give it any more airtime. It was terrible, but it wasn’t nearly as terrible as going to two funerals a week, which was an infinitely worse way that my government was trying to destroy queer people’s lives, through inaction. Eight years of not saying the word AIDS from the White House until 90,000 Americans had died. In comparison, it was a pain in the butt, but it wasn’t keeping me up at night.