Montreal’s Promise of a Sanctuary City Falls Short

Health Care, Education and Work are Still Out of Reach for Non-Status Montrealers

Montreal declared itself a sanctuary city in February. As the declaration made headlines around the island, newcomers and other undocumented people were given the hope that they would now be able to live with less fear of deportation.

The city pledged to ensure that mechanisms would be put in place to allow undocumented people the freedom to use the services provided by the city without the risk of being reported to immigration services. Other promises were made saying undocumented people would soon have more access to housing, would be free to call the police when in need of help, and that those serving non-status people would be properly trained on how to work with them.

Months after the fact, the promises laid out in that declaration have yet to unfold. The city says that it’s in the process of creating an “action plan” with the Bureau d’intégration des nouveaux arrivants à Montréal, le service de la diversité sociale et le service des Finances.

From March to June, 16 different consultations were conducted by the Bureau d’intégration des nouveaux arrivants à Montréal, and other groups. Internally, consultations were held with the municipal bodies that provide services to non-status people, and with community groups in Montreal that focus on providing health care, education, and other support to non-status people.

Other consultations were held with ministers on the provincial and federal level. Spokesperson for the city, Linda Boutin, said that the discussions mainly focused on health care, social services, housing, and legal rights. But for the most part, what’s been done so far remains a secret as the city will only reveal the finer details in a public announcement set for an unknown date.

Defining a Sanctuary City

The term “sanctuary city” is often a bit of a misnomer, and the definition of what it really is depends on who you ask. So far, the term carries no legal definition in Canada.

Despite it’s fluid definition, most grassroots organizations focused on protecting undocumented people from deportation, and researchers interested in the question argue that for a city to be considered “a sanctuary,” the minimum requirement is that it makes a commitment to not collaborate with immigration enforcement.

“Immigration still does its work there, but without the collaboration of the police,” explained David Moffette, an assistant professor and researcher from the department of criminology at the University of Ottawa.

At the very least, he says it should also include a “don’t ask, don’t tell” type of policy, where “all city services, and all agencies funded by the city refrain from asking any information about immigration status. And if they find out, refrain from passing on this information to anybody, but especially to the [Canadian Border Services Agency].”

In Montreal, that would mean police ending or limiting their collaboration with the CBSA. Doing so would decrease the number of undocumented people being deported from Montreal, but it’s unclear to what extent the Montreal police would look to limit that work.

When asked whether the city would look to end collaboration between the Service de Police de la Ville de Montréal and the CBSA, Boutin declined to comment.

Daniel Touchette, assistant director with the SPVM, explained that since Canadian police officers are obliged under federal law to enforce immigration warrants, there are barriers in the extent to which Montreal police can cease communication with the CBSA.

Beyond that, some undocumented people who don’t have immigration warrants could still get reported to the CBSA by the SPVM. Touchette explained that undocumented people who have criminal charges, or who are facing security-related charges, will be liable to being reported to the CBSA—even if the CBSA hasn’t issued a warrant for their deportation.

The problem with this, Moffette says, is that it has the power to create a dichotomy between the “good” immigrant versus the “bad” immigrant.

“This policy will only apply for the good immigrant,” he says, “as though it was so easy to distinguish between the two.”

“This policy will only apply for the good immigrant, as though it was so easy to distinguish between the two,” — David Mofette

Continued Deportations

Although we know that people are still being deported as a result of interacting with the Montreal police, it’s hard to determine the exact amount of people currently being deported from the city.

Anecdotally, groups like Solidarity Across Borders, a migrant justice group that focuses on directly giving support to undocumented people and protecting them from deportation, say that they are frequently told stories about undocumented people being deported as a result of minor infractions with the police.

“Not only are there quite common and active interactions between the police and the CBSA, but in many ways the police are proactively turning people in based on those interactions,” says Jaggi Singh, a veteran activist and member of Solidarity Across Borders.

“We hear stories all the time about people who face deportations,” says Stacey Gomez, another member from the group.

They say that they have heard dozens of stories about people being reported to the CBSA, and then later being deported as a result of traffic violations, hopping metro turnstiles, and, in one instance, for being caught riding a bicycle without a reflector. It’s hard to determine whether these events occurred as a result of those people having warrants for their deportation, or as a result of police inquiring about their status.

In accordance with the declaration made by the city, Touchette says that officers have started referring undocumented people to immigration lawyers at the Centre d’aide aux victimes d’actes criminels who can try to help them get legal status. He also says that it’s not within the Montreal police’s jurisdiction to ask people about their status.

“We’re not going to randomly stop someone on the street, and start inquiring about their status. We can’t do that,” notes Touchette.

Data from the past two years shows otherwise.

In an Access to Information Request filed by Moffette that was provided to The Link, records from the last two years show that Montreal police frequently collaborated with the CBSA to inquire whether or not someone is liable for deportation. This collaboration was often done through phone calls to the CBSA’s warrant response call centre, where Canadian police can verify whether or not a person has an immigration warrant for their arrest by the CBSA, or whether they have status.

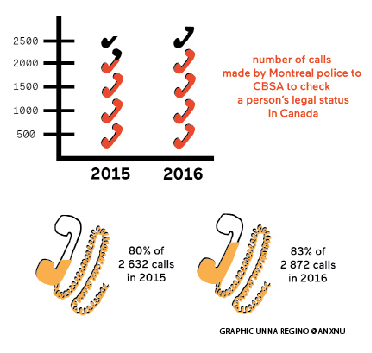

In 2015, Montreal police made 2,632 phone calls to that centre. Eighty per cent of the time, it was to check a person’s status because they had a suspicion that the person might not have legal status in Canada, and therefore may be of interest to CBSA.

Throughout 2016, Montreal police made 2,872 calls to the same centre, and similar to the year before, 83 per cent of the time, it was to inquire about a person’s status. In a follow-up interview with The Link, Montreal police reiterated that calls made to the CBSA are only supposed to be made if there’s a criminal investigation in process against a person.

Touchette said that while this is the only time Montreal police are supposed to call to check status, the data obtained from the CBSA is not detailed enough to confirm whether or not this the case. “They call not to verify an immigration warrant, which, by law, the police technically have to enforce,” says Moffette, “but in a lot of cases it appears there’s no warrant, and they go out of their way to say ‘hey we have someone over here without status.’”

So despite it not being within their duties, in the past two years we know that Montreal police still made an effort to ask people about their status when they suspected a person may not be here legally. Right now, it’s hard to judge the extent to which this same practice is done by Montreal police in 2017. But if the culture for so long has been to collaborate with the CBSA, is it realistic to think that this would change anytime soon?

Some would say no, while others would argue it’s a matter of political will.

Real Sanctuary Cities

Because of the continued deportations, Gomez from Solidarity Across Borders argues that Montreal is nowhere close to genuinely being a sanctuary city. Other anti-deportation groups like the Non-Status Women’s Collective of Montreal and the Comité d’action des personnes sans statut also agree.

“What a sanctuary city should be is people without status feeling safe, and feeling safe from the risk of being deported. So far, that’s not the reality,” she says.

While Solidarity Across Borders says it’s a good step forward to be more open to incoming migrants, they say the declaration itself is dangerous because it gives people false hope, and false information.

They want the SPVM to stop working with the CBSA, but that’s not the only thing they’re asking for. Gomez hopes to see an implementation of an official “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy within the police force, similar to one found in Toronto. She also wants to see the end of “double-punishments,” where undocumented people get punished for having criminal charges by being reported to the CBSA.

Beyond that, with the philosophy that no one should be illegal and that there ought to be no borders nor nations, Solidarity Across Borders’ larger aspiration is to see status granted to all migrants who come to live in Canada.

To them, the ideal sanctuary city would not just give the bare minimum to undocumented people, but would also create the conditions necessary for them to thrive. It would allow undocumented people the ability to access legal work, affordable health care, and to pursue education at all levels. But even if all the promises laid out in the declaration were met, undocumented people in the city would still be lacking access to many essential services.

Here’s A Breakdown:

Access to Health Care

First, medical insurance under the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec isn’t available to people without status, and those in need of care at a hospital will pay the same price as a visiting tourist. Hospital fees double for those not covered by the RAMQ, and so many without status can’t afford to pay. Because the RAMQ is under provincial jurisdiction, there’s not much the city can do on the municipal level to change it.

As a result, many non-status people have an aversion to going to hospitals, explained Magalie Benoit, a migrant health researcher from Université de Montréal’s institute of public health.

Some also avoid hospitals out of fear that it’ll draw attention to their immigration status. While she says it’s rare, employees in hospitals occassionally, although inadvertently, alert immigration of non-status people when they call immigration services to check if a patient is applicable for coverage.

“People tend to avoid going to hospitals if it’s not really bad, because they’ve heard that people have gotten deported as a result of going to the hospital. So they’re afraid,” Benoit says.

Access to Legal Work

Undocumented people don’t have access to social insurance numbers, and as result, cannot work legally. Since the federal government rules over this matter, there’s little the city itself can do about this, beyond putting pressure on the federal government.

Not having access to legal work inevitably puts non-status people at a disadvantage. Often their pay will not meet the minimum wage, and they will not be able to make use of labour laws that can be used by regular citizens when faced with injustices from their employers.

Access to Education

When it comes to elementary school and high school, families without status are often forced to pay high fees if they want to send their children to school, since children without refugee status, Canadian citizenship, or permanent addresses are exempt from getting free education. Those who fall within those categories pay fees in the thousands, with the going rate for a year of kindergarten education for one child being $5,755. For a year of high school, it’s $7,172.

This is in contrast to Ontario where, regardless of status, anyone aged six to 18 is able to receive free primary and secondary education.

While school boards can technically make exceptions, Steve Baird from the Collectif éducation sans frontières—a group that gives to support and advice to non-status families looking to put their children into school—says this is not often the case.

“In our experience, people don’t get told they can make an exception, they get told, ‘If you don’t have a status, this is how much you need to pay,’” he explains.

Minister of education Sébastien Proulx hopes to see the law changed with the adoption of Bill 144, which would give better access to primary and secondary schooling for children without status, among other things.

At the university level, getting in is comparatively much easier. That being said, fees for international students are much higher than those for students from Quebec or other provinces, and the high prices may be a deterrent for many non-status people already in a precarious situation.

Solidarity and the Right to the City

The ideal sanctuary city would create the conditions necessary for undocumented people to thrive, but Solidarity Across Borders hopes to broaden on that ideal to turn Montreal into what they call a “solidarity city.”

2_900_1350_90.jpg)

In a solidarity city, a strong sense of community would be shared between neighbours. Neighbours would support each other, especially those in precarious situations, and would help each other in their efforts to get access to essential services, regardless of status or social class. Barriers imposed on lower class people because of gentrification would be looked at as goals to overcome, rather than ignore.

“A solidarity city, from my perspective, is trying to change the culture that we live in,” says Gomez. “It emcompasses the principal of mutual aid, and also its different groups in the community that are signing the declaration saying that regardless of what happens at the municipal level, they’re going to offer their services without asking for people’s immigration status.”

Borrowing ideas from anthropologist and critical geography professor David Harvey’s idea of the right to the city, residents in a solidarity city would also focus on collectively shaping their city according to their own needs, rather than being at the whim of municipal politicians.

“The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city,” writes Harvey in his 2008 book titled The Right to the City. “It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.”

Singh says that as Montreal continues to makes strides in becoming a sanctuary city, the more likely it is that injustices faced by undocumented people will reach the public eye.

Currently, he says, these injustices tend to be masked since non-status people are too afraid that being in the public eye and challenging the status quo will lead to them getting expelled from the country. But to them, a solidarity city is essential if we really want to bring to light the issues non-status people face.

1_900_600_90.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)