Meru Brings You Close to the Edge

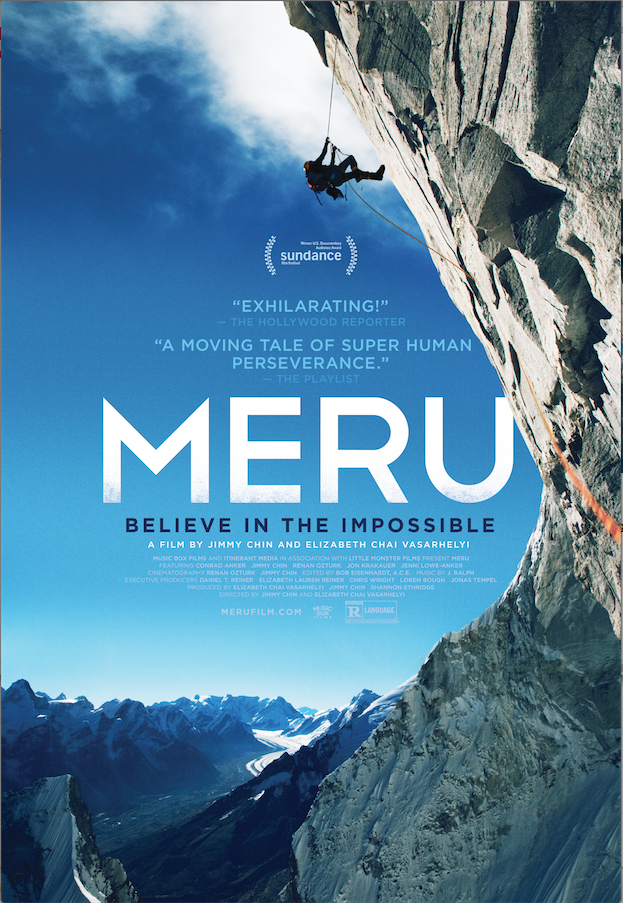

Meru, an indie documentary about three of the best climbers in the world on a multi-year mission to climb the toughest mountain in the Himalayas, filmed by two of National Geographic’s best artists, wasn’t exactly destined for failure.

Produced by Music Box Films, directed by Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi—a power couple team—and edited by multi-Emmy-winning and Oscar-nominated human Bob Eisenhardt, Meru is sick. It won the Audience Choice Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Meru tags along with Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin, and Renan Ozturk during and between their first-ascent attempts of Mount Meru, deep in the Indian Himalayas, in 2008 and 2011.

They make an interesting team. Anker, the veteran climber with a dark past but the know-how to pull off the climb. Chin, the director, the National Geographic photographer, the maniac who skied down Mount Everest. Ozturk, the young buck, the National Geographic cinematographer, the person I follow on Instagram. I actually follow all of them on Instagram, full disclosure.

Meru, the mountain, is also a character. The character. Chin and Ozturk do a terrific and ingenious job of capturing its nature during their two climbs. Varying between gritty point-of-view shots and pristine time-lapses, switching from snow-specked action to intimate moments of rest, the experience of being on a big, dangerous, living peak is well-represented. It’s hard to make what’s basically a 19,000-foot-tall rock feel malevolent, but they do.

There are spectacular scenes that you should go see and definitely not let me struggle to describe, but let me give you a taste. On the second day of the 2008 climb, the team set up their portaledge—a tent that you nail to the side of a mountain, basically. Almost immediately after, a storm rolls through the range and sets off avalanches above them. The walls of the portaledge flutter, the structure shakes and the roar of a thousand tons of snow spilling down the cliff is, uh, heard. The only view you have is from inside the windowless tent, but Chin and Ozturk make you feel like you’re about to die. Visceral is too dry a word to describe the experience.

It’s good that they capture the mountain so well, because Meru is integral to the movie’s very human drama. Again, these are things better seen than described, but there’s a visual motif where the mountain is filmed from a few miles away, at night. The milky way rises above it, but you can still see the climbers’ headlamps from the distance, inching their way up.

Despite the enormity of the mountain and the infinity of the cosmos behind it, it’s the humans that stand out. It’s their lights that burn brightest. It’s their struggle that makes them worthy. The mountain only serves to amplify them. It’s a nice metaphor for the whole movie.

Meru has a big problem, though: women. The “girls back home” exist to flavour the men’s lives, nothing more. No mention of how Jenni Lowe-Anker is an author and an artist and runs a charity for Nepalese people. Grace Chin demonstrates Jimmy’s kind nature by narrating how, when she was in rough times, her brother let her live with him. Renan’s girlfriend and environmentalist, Taylor Rees, disappears from the movie until he makes the decision to go back to Meru. Then she shows up, says “He didn’t ask me,” and disappears again.

The attitude that women are holding back men is a recurring, hopefully unintentional, theme in the movie. There’s Rees, who pretty reasonably doesn’t want him to go back to the mountain after he almost dies. And Anker, on their first failed attempt when they’re 100 metres from the summit, narrates his thoughts. “If I die, I’ll really fuck it up for my wife and kids,” he says—as if being married is preventing him from doing this great thing? And Chin tells a story about how his mother made him promise that he wouldn’t die before her. When she does die, he literally says, “Well, I can go for it now.”

Sure, it speaks to the way that these men’s dreams took hold of them, and of the conviction needed to do great things. But you can be driven without being subconsciously misogynistic, right? Maybe if the film explored how the families dealt with danger and fear, then the women’s voices would be stronger. But their strong voices would still only belong to bystanders, so. Maybe that’s the point? Maybe, since some of the film’s Wild ‘n Free men do die, it’s a macabre critique of traditional masculinity? That’s probably too generous, in any case.

If you’re willing to overlook the questionable gender morals of Meru —and it really wants you to—it’s a near-perfect film. If you’re not, it’s not.

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)