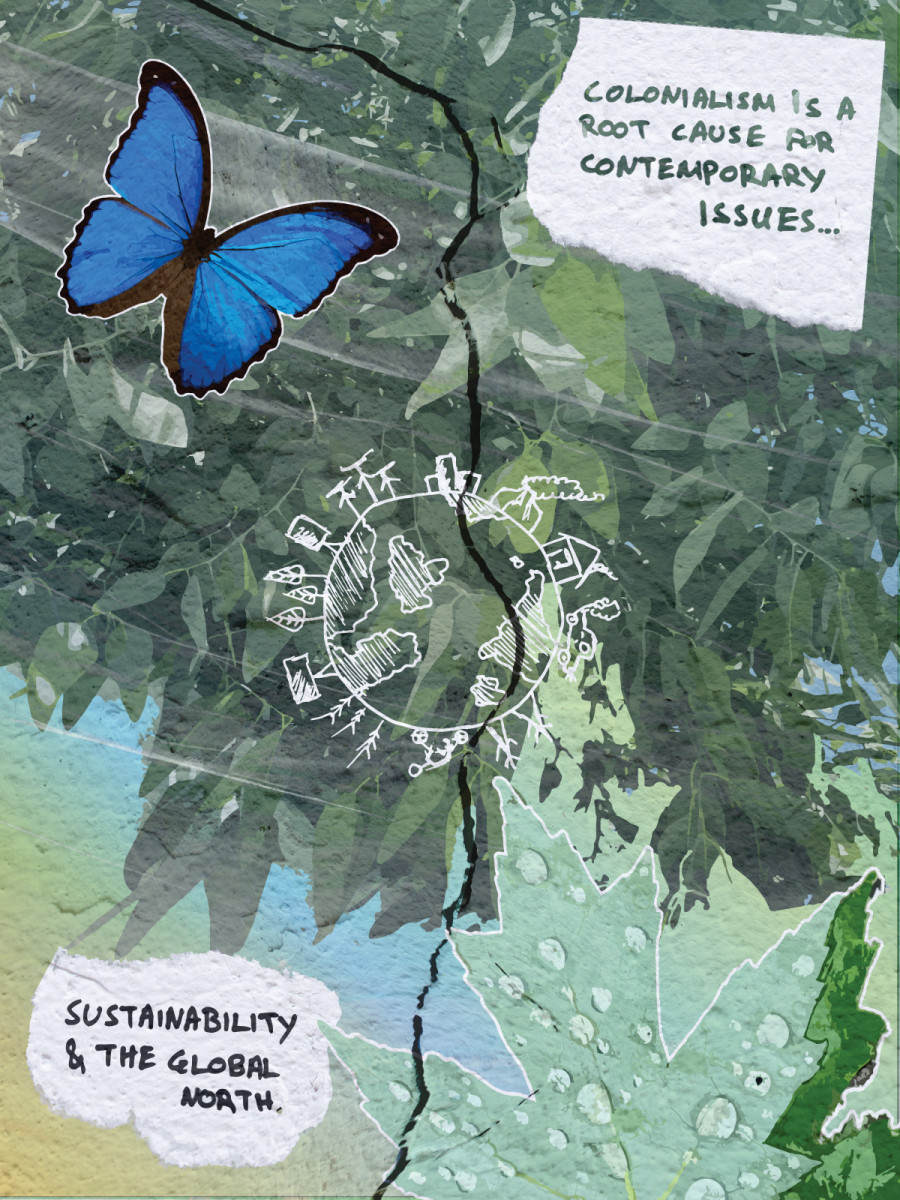

It Starts With De-Colonization

If What We Want is Sustainability, We Have to End Colonialism

Within Canada, we have a massive role to play in transforming our world towards sustainability, which includes openly naming colonialism as a root cause for contemporary concerns like our global food systems and climate crisis.

In a piece published by The Narwhal about mining in foreign countries, Andrew Findlay reminds us that “Canada is the undisputed powerhouse of the mining industry, home to 75 per cent of its companies. Figures from the Mining Association of Canada show that Canadian investment in mining abroad more than tripled between 1999 and 2016.”

I, Meredith Marty-Dugas, am the Sustainability Ambassadors Program Coordinator in the university’s Office of Sustainability (OoS). My position started as a collaboration between Concordia and Sustainable Concordia’s (SC), while I was a student and working part-time. I’m also a poet with a never-ending to-read list, a lover of reuse with six projects going at once, and a prison abolitionist.

Duha El-Mardi is the fee-levy SC Engagement and Education Coordinator. She is also an amazing community organizer, Sudanese activist, projects coordinator at the Sustainability Action Fund, Master’s student in Human Systems Intervention, and holds degrees in Community Economic Development and Environmental Studies.

We must start by clarifying who we are, what we do, and how our shared trust and respect allows us to imagine new futures and partnerships so that we can resist the capitalist and colonial expectation to disappear behind our positions and the institutions.

Duha and I develop and provide learning opportunities for students and the public that teach about the effects of colonialism and the necessary steps we must take to achieve a sustainable future. Educational programs will not replace the required active resistance to governmental and corporate extraction of nature. Rather, we are aiming to facilitate solidarity across diverse groups of people to prepare them for this tough work ahead. To do that, we must practice very intentional, transformative care for everyone and in the ways people are ready to participate. We must disrupt the idea that anyone is disposable and instead prepare ourselves to be a part of something bigger than us.

Universities are structures, but they are also people. It is our investment in our relationships, in fostering connections and complexity, that allows us to move forward into creative solutions for sustainable futures that include everyone, not just white academics worried about carbon emissions. We must talk about underprivileged Black and Indigenous communities living near landfills, contaminated waterways, pipelines and mines, who witness firsthand the violence that permeates our environment; as well as refugees that have been displaced by climate crises and violence spurred by extractive industries; and moose that are losing their fur to tick allergies because warmer climates keep bugs alive longer; the city kid breathing in too much smog; the monarch butterfly that is losing its own migration pattern; also the right whale that is trapped in our fishing nets; also; also; also.

In 2017, Robert Jago published an article titled “Canada’s National Parks are Colonial Crime Scenes.” In it, Jago details how conservationism that celebrates wilderness in Canada is a colonial fantasy built to gloss over the murder and theft of Indigenous people and their relationships to nature. Jago claims that “throughout these years, continuing to this day, thefts have been occurring under the guise of ecological preservation—green colonialism.”

Jago details how the borders created by white colonizers under the guise of protecting nature have been used to justify the eviction of nations who have lived there for thousands of years. Since the late 1800s, Canadians have been using the nostalgic wild fantasy as a tool to abduct and criminalize Indigenous relationships to land.

By making white government administration responsible for care of our landscapes, the rights of Indigenous nations and communities living on the land have been greatly restricted. Instead, this ideology pretends that these communities pose the same kind of destructive threat to nature that colonization and colonial extractive industry does and therefore must be alienated from the ecosystem. Unfortunately, this forced segregation of social justice and environmental justice remains in many powerful places today, including in how universities teach about sustainability, as a way to maintain white supremacist settler states like Canada.

There are, of course, beacons of hope. Ingrid Waldron’s research in collaboration with Black, Indigenous, and lower income communities on issues like environmental racism has brought the subject to the mainstream, including the Elliot Page-produced and directed documentary There’s Something in the Water. Projects like Rural Water Watch and the ENRICH Project, continue to demonstrate how mutual respect and support can benefit academic research and the communities most affected by issues like the climate crisis and poor waste management.

Neither Duha nor I are researchers, but we hope that our partnerships and programs offer our community renewed perspectives on the connection between community and ecology. We each have opportunities to do so through the educational programs we design and deliver. When I teach the “Introduction to Sustainability for Employees” module, alongside traditional definitions, we include a history of sustainability that begins with modern colonialism. In the student Sustainability Ambassadors Program, Duha joins me so we can talk about how environmental racism is created in Canada through regulatory systems and corporate greed.

We also facilitate conversation so everyone has a chance to position ourselves in relation to our pasts. Meanwhile at Sustainable Concordia, Duha facilitates a session about the ways we can integrate a decolonial and anti-oppressive lens to environmental justice in “Organizing Sustainability” to introduce community-centered organizing for environmental justice campaigns.

Defining our beginning is imperative to defining how a problem comes to be, how it continues to work.

The modern wave of colonialism began in the 15th century with the Catholic church’s Doctrine of Discovery. This issued a justification for mass murder and pillaging as a glorious duty from God. The Church considered land without Christians on it to be “unoccupied” and obliged colonizers to exploit the resources and people they came across. This ideology that allowed for the destruction of other nations and the worlds they inhabited; that broke people and nature down into bits and pieces, still affects us today. It is found in the racist conservation strategies of our national parks and the extractive industry so-called Canada manages globally.

Colonialism is the man behind the curtain, acting as the architect of the climate and social crises we now hope to solve. By acknowledging that these issues are directly caused by colonization, Duha and I aim to find new strategies for achieving sustainability that destabilize white institutions as the sites of solutions.

We cannot diffuse the responsibility of the climate crises onto everyone equally. For instance, the entire continent of Africa makes very little emissions in comparison to the colonial powers of the Global North. Although we all have responsibility to work towards sustainability, our responsibilities are different. My own relationship to being sustainable is in direct relationship to my family’s history as colonizers of Turtle Island. That is a legacy I must carry and disrupt, as I reconnect with the land and environment I am in.

Together and separately, facilitating anti-colonial approaches to sustainability is what allows Duha and I to bring joy and hope into hard work. We imagine futures and worlds outside a narrow, white supremacist lens where building, nurturing and sustaining healthy and happy communities is always the priority.

Duha and I hold very specific responsibilities to each other, our employers, communities, students and attendees. We are in continual conversation about how we remain accountable and approach this position ethically. By taking anti-colonial approaches to sustainability, we restore opportunities for our community to collaborate, to dream up worlds that white supremacy tells us is impossible. The fight is not humans versus nature, the fight is us versus white supremacy and the industries that power it. It is our multiplicity that allows us to welcome different people on different journeys and focus them on the same goal: to achieve wellbeing for everyone, plants, animals, rivers, mountains, mycelium, and more.

Colonialism is the problem we are trying to solve, sustainability is the (re)new(ed) world we are working to achieve.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 13, published March 7, 2023.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)