Editorial

Standing With the Faculty

We’re reaching a breaking point when it comes to labour negotiations at Concordia.

Last week, our full-time professors joined the ranks of our part-time faculty and steelworker unions by voting in favour of a strike mandate—a first for the Concordia University Faculty Association.

With this strike mandate vote passed, Concordia’s entire faculty could legally walk out following a 48-hour notice. And while all three unions giving a strike notice at once is unlikely, it leaves Concordia’s labour climate more tense than ever.

Despite fresh faces at the top of our administration, several of those at the table have told us that they are seeing little change.

And what’s unfortunate is that the sorry state of labour relations at Concordia is nothing new. Concordia unions say they’re fed up with the attitude of the negotiators they have to deal with; that meetings never amount to anything but arguments.

The Quebec union umbrella group Confédération des syndicats nationaux has told our library employees union that no one’s worse than Concordia when it comes to drawn-out negotiations. Our library workers are facing delays even with their collective agreement, which has been expired for over three years.

With Concordia’s trade workers and both full-time and part-time faculty mandated to consider their most extreme option, it’s time to look at what exactly causes such a climate on the administration’s part, and why exactly it’s common knowledge that painfully unfruitful labour negotiations are just business as usual at Concordia.

This becomes especially true when this year we have so many new administrators governing the university. If things are ever to improve, now is the time.

While upper admin get perks like luxury cars on top of their salaries, steelworkers aren’t even offered increases comparable to the rising cost of living .

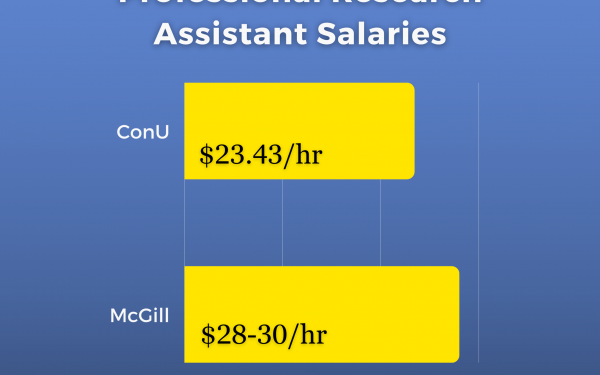

When justifying the salary increases to upper administration, the oft-repeated argument from the university has been that they’re necessary to get the best candidates for the job.

It’s a point, however, that largely seems to be skirted by the university when looking at anyone a few rungs down on the labour ladder. While Concordia can’t comment on negotiations currently underway as a matter of policy, the contradiction in when and where the university sees

the need for competitive salaries can’t be ignored.

CUFA argues that they’re making 13 per cent less than what other profs make at comprehensive universities. We find it hard to believe that competitive salaries are only important for upper administrators.

And, of course, this is coming from a university with a reputation for handing out hefty parting gifts to administrators on their way out—actions that resulted in $2 million in fines from the provincial government for mismanagement of public funds.

When professors lose out, we lose out. Where is it more important to get quality employees than those responsible for designing courses and engaging students? After all, that’s what we’re here for.

The fact that our degrees are potentially in jeopardy shows just how bad things are getting.

Nobody wants a strike, but at this point our professors are being backed into a corner, told that money’s tight. It’s a hard pill to swallow when such number crunching only seems to come into play when we’re talking about our worker’s unions.

Concordia President Alan Shepard has said many times that his priority is improving Concordia’s reputation. And with Shepard as the face of our university and with a very different Board of Governors this year, there is real hope that this is the end of our governance crisis.

However, the chance of our faculty striking derails all this—and as students, the stress mounts ever higher when we’re not sure if we’ll be able to get the credits we need to graduate.

If this emerging crisis isn’t resolved, it’s what we’ll be known for—even outside of labour union circles. Forget the golden parachutes. We’ll be remembered as the school that came to a grinding halt.

(WEB)_900_409_90.jpg)

less_pink_copy_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)