Editorial: No innovation without compensation

In April 2023, Concordia University announced it received a $123 million grant from the Canadian government to “electrify society.”

With this grant from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, Concordia has joined at least seven other universities in working with “Indigenous, private, public and not-for-profit sector experts to deliver integrated, affordable decarbonization solutions, focused on electrification.”

“Concordia aims to be a world-leading institution… using technological and social innovation,” read the university’s grant announcement last year.

Since 2017, innovation has been one of the most used buzzwords by the Concordia administration. Its desire to be seen as a “next-generation university” has driven the bulk of its technology-centred decisions.

But what makes a “next-generation” university? Concordia’s then-president Alan Shepard defined it as “trying to align the quality of teaching and learning opportunities to larger trends and the grand challenges facing society.”

Neoliberal institutions like Concordia rely on public-private partnerships to foster economic growth, despite their state funding. Our university’s next-gen plan is a business venture disguised as a community-based and sustainability-driven effort for innovation and improvement.

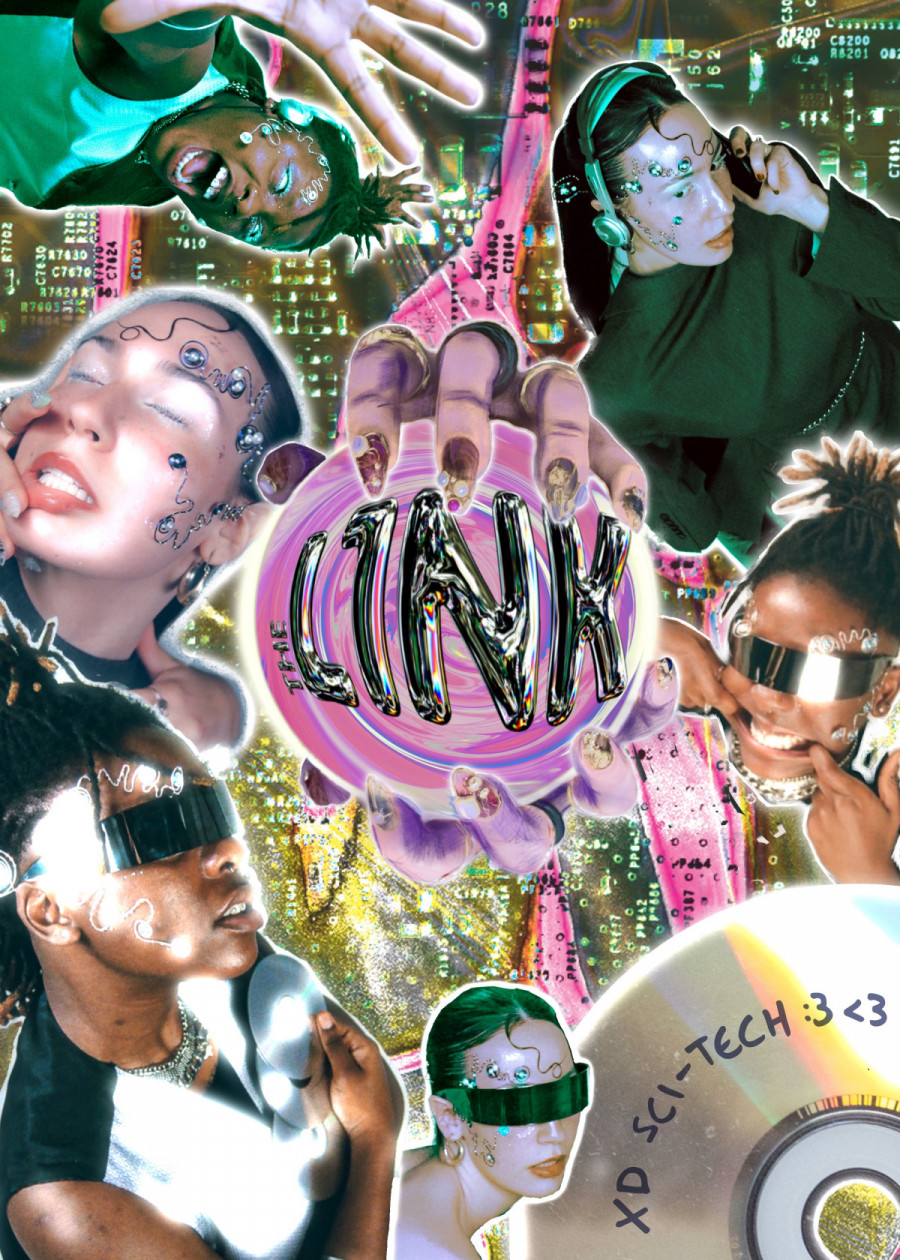

Throughout our special Science and Technology Issue, The Link’s goal is to answer this question: what should genuine innovation look like beyond a bullet point in a shareholder presentation?

We believe that in order to reach a zone of innovation, we first need to achieve proper work accommodations for all members of our community. Accommodations for unionized Concordia workers currently in the bargaining process for a liveable wage. Accommodations for students, teaching and research assistants and faculty members forced to be in the same classroom with their abuser. Accommodations for disabled students who have repeatedly been disappointed by the chronically under-resourced Access Centre.

Let’s use the Access Centre for Students with Disabilities as an example. Concordia previously had an in-class volunteer note-taking program, but it was removed in 2021. This left many disabled students without a way to get notes, unless they were able to get them from friends in class. An easy, innovative fix to this could be mandating professors make all lectures available on Moodle and other similar platforms—class slides and all.

None of Concordia’s innovation plans make mention of next-generation working conditions. At time of publication, Concordia has fought their employees to be in-office a minimum of four days per week, despite remote work having equal or higher productivity. Similar results were found when a four-day work week was tested and successful results were found in the U.K.

Since the return to campus in fall 2021, Concordia has largely abandoned any accessibility measures made available during the COVID-19 pandemic. It regressed in its innovation for the sake of convenience and cost-cutting.

If Concordia wishes to innovate and be a university of the future, it needs to place more power in the hands of its students and workers—not in its corporate administration and donor-hungry class of bureaucrats.

The commitment to science, innovation and progress must be made from the ground up. It means investing in student’s and workers’ welfare and accessibility. We are more than numbers in a budget and deserve to be accommodated equitably.

As put by Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, “the whole of science is bound to needs, to life, to the activity of humanity.” There is nothing more innovative than a university—a hub of knowledge and experimentation—that shows it genuinely cares about the well-being of its community through well-funded services and material support.

We hope this special issue gets our readership thinking about science, technology and the endless possibilities granted when we invest in our communities.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 12, published March 19, 2024.

_600_375_s_c1.png)