Canada Needs Electoral Reform

Canada’s plurality-vote electoral system, colloquially known as “first past the post,” is broken. Depending on which party forms government after Oct. 19, this federal election may well be the last to use this antiquated way of electing Members of Parliament.

A switch to an electoral system based on proportional representation can’t come soon enough.

In Canada, electors vote to determine their local Member of Parliament. The winning candidate doesn’t need to receive a majority of the vote in his or her riding, only more votes than any of the other candidates. Votes for the candidates that come in second, third and fourth place can fittingly be described as “wasted” or “ineffective” votes because they serve to elect no one in this winner-takes-all system.

In contrast, every vote counts in an electoral system based on the principle of proportional representation. Proportional representation can be set up in a variety of ways, but the end result is always the same—each party’s share of the seats in the legislature is a direct reflection of their share of the popular vote.

The first-past-the-post system has a variety of perverse tendencies that make a transition to a system of proportional representation a necessity.

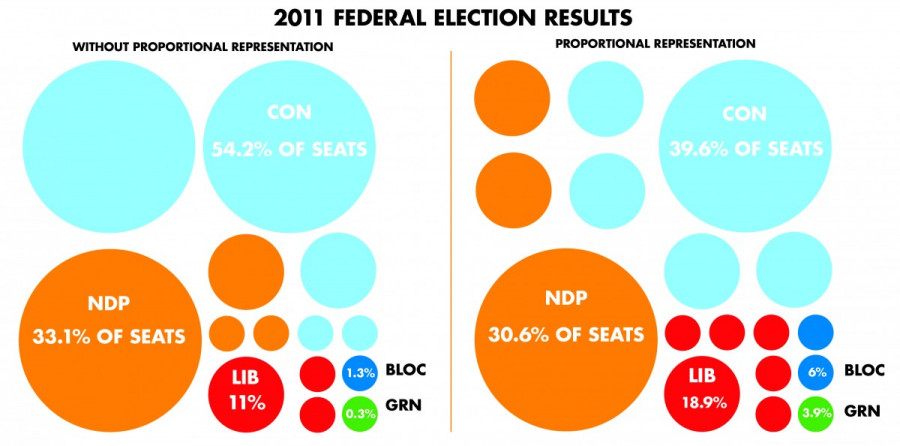

For one, ever since Canadian politics began to move beyond a two-party system in the 1920s, most “majority” governments have been illegitimate. In 2011, the federal Conservatives formed a majority government with 54 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons, despite the fact that they were supported by only 39.6 per cent of those who cast a ballot. Similarly, the federal Liberals managed to win a slim majority of seats with only 38.5 per cent of the popular vote in 1997.

Majority governments in Canada often proclaim that they have a “strong mandate” to ratify their policies, but how can that possibly be true when these governments rarely receive majority support from the electorate? In only three elections since 1921—in 1940, 1958 and 1984—has a party formed a majority government after having obtained more than 50 per cent of the popular vote.

Canadian democracy is therefore clearly at odds with majoritarian democratic theory. Our winner-takes-all electoral system rarely complies with the concept of “majority rule.”

Beyond giving us phony “majority” governments, the first-past-the-post system also distorts the popular vote so profoundly that the resulting seat distribution can seem quite unfair and arbitrary.

In the 2011 federal election, for example, our electoral system wrongly gave us the impression that voters in the Prairie provinces widely supported the Conservatives, Quebecers widely supported the New Democrats, and nobody but some hippy environmentalists in the British Columbia riding of Saanich—Gulf Islands voted for the Green Party.

In fact, almost a third of voters in Saskatchewan opted for the NDP, though the party didn’t win a single seat in the province; 1.6 million NDP supporters in Quebec managed to elect 59 New Democrats, but 1.4 million Ontarians of the same political persuasion managed to elect just 22; and over 575,000 voters chose the Greens across the country, of which only 31,900 went towards electing Green Party leader Elizabeth May in her West Coast riding.

A core principle of democracy—that everyone’s vote is equal—is challenged by our electoral system. Many Canadians cite the “meaninglessness” of voting as the reason why they don’t bother to cast a ballot.

While I don’t want to discourage people from voting, it’s true that a vote in a riding that heavily leans toward one particular party doesn’t have much impact. In contrast, a vote in a hotly contested riding is worth a whole lot. Knowing that an election’s outcome often depends on the results in a few dozen battleground ridings, parties pour considerable amounts of money and personnel into close races while largely ignoring so-called “safe” ridings.

Advocates for the status quo often applaud the first-past-the-post system for creating “stable” single-party majority governments without majority support, as if this were one of its virtues. Introducing proportional representation, they argue, would only lead to unstable minority governments or fragile coalition governments, as well as more frequent elections.

However, these fears are unfounded. Proportional representation could just as easily lead to stable majority governments formed by a coalition of like-minded parties. Most importantly of all, such governments would actually represent the true will of voters.

Of the four national parties, only the Conservatives are firmly opposed to introducing a system of proportional representation. That’s probably because they have the most to lose if such a system were to become a reality.

The Liberal Party has committed to electoral reform in this election campaign, but their stance falls short of unequivocal support for proportional representation. If they form government, the Liberals say they would convene an all-party committee to study various reform proposals, including proportional representation and instant-runoff voting (IRV), an electoral system in which voters rank the candidates on the ballot in order of preference instead of choosing only one candidate.

While IRV ensures that the winner is an acceptable choice for a majority of voters, it’s still a system that results in a high level of disproportionality, favouring large national parties or regionally strong parties at the expense of smaller ones. Australia uses IRV to elect the members of its House of Representatives; election results from that country suggest this electoral system could benefit Canada’s Liberals, who—as a centrist party—would likely be many voters’ second choice.

The NDP and the Green Party, meanwhile, have long supported a move to proportional representation. Of course, they traditionally had the most to gain from this type of electoral reform. Both have stated that they’ll work to introduce a system of proportional representation after this election.

The stances of Canada’s main political parties are therefore all based, at least to some extent, on self-interest.

But the fact remains that electoral systems committed to proportional representation remain the fairest to voters, accurately translating the will of the electorate into the composition of the legislature.

The easiest way to achieve proportional representation would be to have a “mixed-member” legislature, in which we continue to elect MPs in ridings just like we do now, but a certain number of “top-up” MPs would then be added to re-balance the House of Commons and ensure that each party’s share of the seats roughly corresponds to its share of the popular vote.

Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom are the only Western democracies that still use the first-past-the-post method. This electoral system breeds cynicism and results in a loss of interest in politics among many voters. We desperately need a system in which every vote actually counts.

_600_832_s.png)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)