Bonjour/Hi

Bienvenue à Montréal, ville bilingue

This article has been updated.

“Sometimes conversations that make you feel nervous are good ones to have,” said Susan Edey. “A lot of magic can come from bilingual conversations.”

But as a non-Quebecer, Edey didn’t feel entitled to host one at first, since languages are such a politically sensitive matter in the city.

D’après elle, tant de gens sont bilingues dans la ville qu’il est cause de stress pour ceux qui ne le sont pas de s’exprimer dans leur seconde langue. Il est de plus relativement simple de vivre dans sa propre bulle linguistique, dans une ville où les deux langues sont accessibles.

Dans la pièce du café bistro le Fixe, chacun prend la parole pour faire part de son expérience avec la langue, dressant un portrait coloré de Montréal et de ses différentes facettes. Des anglophones parlent des difficultés à pratiquer le français à Montréal, les services de la ville passant automatiquement d’une langue à l’autre en percevant un accent dans la voix de leur interlocuteur.

Languages shape experiences and environments. A unique feature of Montreal’s identity is bilingualism. Despite the obvious cultural richness that it brings to the city, it also creates a dual reality.

“Montreal is a place where languages meet,” said Jimmy Ung, moderator of the discussion “Living Language in Montreal” that took place last Thursday.

The discussion was presented by University of the Streets Café, a bilingual conversation group giving a voice to Montreal’s diversity. It offers a welcoming space for students and citizens to debate in French or English. The last meeting explored the unique linguistic specificities of living in Montreal.

The topic of the conversation came from within the setting of this series of talks, where everyone could express themselves in their language of predilection, said Kit Racett, a regular attendee who initiated last week’s theme of conversation.

“This is so wonderfully Montreal,” Racett said.

View post on imgur.com

According to Statistics Canada, there were nearly 2 million bilingual people in Montreal in 2011. Young Quebecers have a high rate of bilingualism, set at 80 per cent.

Even though bilingual people make up a majority of Montreal’s population, other groups do coexist in the city. Around a million people are unilingual francophones and there is a growing number of allophones, people whose mother tongue is neither English nor French, that move to Montreal.

Statistics Canada data also demonstrated that an increasing number of immigrants become bilingual by learning French, and not English. This leads to new dynamics in the cohabitation of the two groups in the city.

Élisabeth Couture and Gail Marlene Schwartz are members of Promito Playback Theatre, a troupe which puts on plays where the audience is encouraged to share their stories and interact with the comedians.

For Couture, being bilingual and growing up in a multicultural family was a painful experience and a source of conflicts.

“Ce qui est déchirant est d’avoir un pied du côté francophone et anglophone simultanément,” she said. The two cultures are separated, they coexist but never blend together or embrace each other.

“Ce qui est déchirant est d’avoir un pied du côté francophone et anglophone simultanément,” – Élisabeth Couture, member of Promito Playback Theatre.

Couture witnessed the language situation evolving in Montreal throughout the years but said she thinks the divide between the eastern and western neighbourhoods of the city is still as present as before.

She added that the way people perceive their environment is determined by their cultural origin, and this is why she felt the need to highlight the challenges of the complex situation in Montreal.

Couture and Schwartz created a community called Crossing the Main. Struck by how the artistic communities of the city were divided by language, they wanted to create a safe space for each to share their experience with language tensions.

Couture explained the goal of the project was to initiate a dialogue between the two communities on the subject of language and culture, in order to facilitate understanding.

Crossing the Main organized three performances, one in English, one in French and one bilingual. Schwartz expressed how surprised she was to realize most of the audience for all three performances was made up of immigrants.

Many anglophones attended the bilingual performance. After the show, the feedback she received from them was unsettling. They felt they did not have the space to participate, she said.

This episode highlights how language is a source of tension in the city.

One attendee at the talk, Jordan Levinson, said there is a historical context that we need to keep in mind—the issue is more political than linguistic. Raised in the U.S., he explained that there is much more to the world than just the English language, and that it is enriching to learn to live and coexist with French people who think and approach issues differently than him. He quoted Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian-British philosopher—“the limits of my language are the limits of my world ”—asserting that Montrealers need to keep some connection to the place in which they live.

“As anglophones, we need to respect the boundaries the French set,” he added. “They have their world that they have been protecting from the English imperialism for years now.”

Schwartz recalled her first encounter with Montreal when she moved to Canada years ago from the States and she first heard a “casual reference to the language police,” which she found extremely offensive.

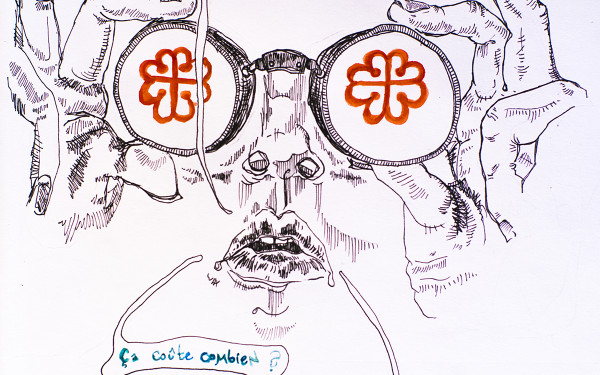

“The language police” is the way some Montrealers refer to the Office québécois de la langue française. The OQLF regularly intervenes in the city to insure their rules are respected, such as the one requiring French text to be larger than English text on signs.

Schwartz understood later how existing within a predominantly English country is a source of tension for the French community of Quebec. As an American Jew, she related to Quebecers’ fear of loosing their fragile francophone culture and compared it to her own experience with Yiddish, which disappeared in her family over two generations.

D’autres langues sont en voie de disparition. À Montréal, ville établie sur le territoire Kanehsatà:ke, la réalité linguistique n’est pas que double. Les populations autochtones se battent pour préserver leur héritage culturel. Le groupe Montréal Autochtones offre des cours de langue Innu, Cree et Mohawk, et les classes sont en sureffectif.

Pendant la conversation au café le Fixe, francophones et anglophones partagent leurs expériences, répondant à une langue dans une autre. L’existence même de ce débat bilingue représente l’essence de l’identité montréalaise, bien que chacun se présente d’abord par sa langue d’origine. La discussion permet de mettre en lumière les difficultés des différentes communautés de la ville qui rentrent parfois en confrontation.