Abusing Stimulants: Students are Still Relying on Adderall to Study

Stimulants Often Used Without Prescription, With Many Selling or Giving Out Their Pills

The first time Cora Miller* took what she calls the “get-ahead drug” she was studying with a friend in a Grey Nuns reading room—they thought it would be fun.

At the time, she was taking a philosophy course and had to write a paper that night. She was lost, wondering, “What the fuck is going on,” then she took Adderall and thought, “It all makes sense now!”

To protect the identities of those who use and distribute stimulants illegally, The Link has granted anonymity to allow students to speak on record. The names used are pseudonyms.

Miller said the experience reminded her of a scene in the movie A Beautiful Mind. “John Nash [played by Russell Crowe] is seeing the codes and symbols and he’s underlining everything,” said Miller. “That’s what I felt my first time doing Adderall.”

That was three years ago. During a phone interview with The Link, she said that when she does Adderall now, “I sometimes wish I [still] felt like that.”

For those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or narcolepsy, drugs like Adderall and Ritalin help stimulate the central nervous system. ADHD drugs enhance the brain’s ability to signal for the release of dopamine, a key regulator of motivation and cognition. As prescription stimulants, they’re classified as Schedule III drugs in the Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. The act regulates the production, sale and possession of drugs that are dangerous when misused. Substances are categorized based on “harm to public health or safety.” Possession is legal when prescribed by a licensed medical practitioner.

Miller, a third-year political science student at Concordia, said she uses Adderall or Vyvanse once every two weeks, unprescribed.

Of Miller’s closest friends, she said half abuse Adderall for academic purposes.

Drugs for ADHD can be separated into three categories: amphetamine-based stimulants, methylphenidate-based stimulants, and non-stimulants. Adderall, Vyvanse and Dexedrine are amphetamine-based. Ritalin, Biphentin and Concerta are methylphenidate-based stimulants.

Non-stimulant ADHD drugs, like Strattera or Intuniv, according to the NCAA, are not as effective in treating ADHD symptoms, but the Canadian Pediatric Society asserts that they have a low potential for abuse.

In the U.S., a comprehensive analysis of over 20 studies was conducted in 2015. It described misuse of stimulants as a “prevalent and growing problem.” It estimated stimulant misuse by college students to be at a rate of 17 per cent.

In Canada, in the 2013 National College Health Assessment, 3.7 per cent of more than 33,000 postsecondary students from across Canada reported illicit use of stimulants. A 2018 survey conducted by a doctoral student at Dalhousie University reported similar outcomes: 6.8 per cent used stimulants, and about 80 per cent of those who didn’t have a prescription. 88 per cent of the misusers specified that they used non-prescribed stimulants to help with studying.

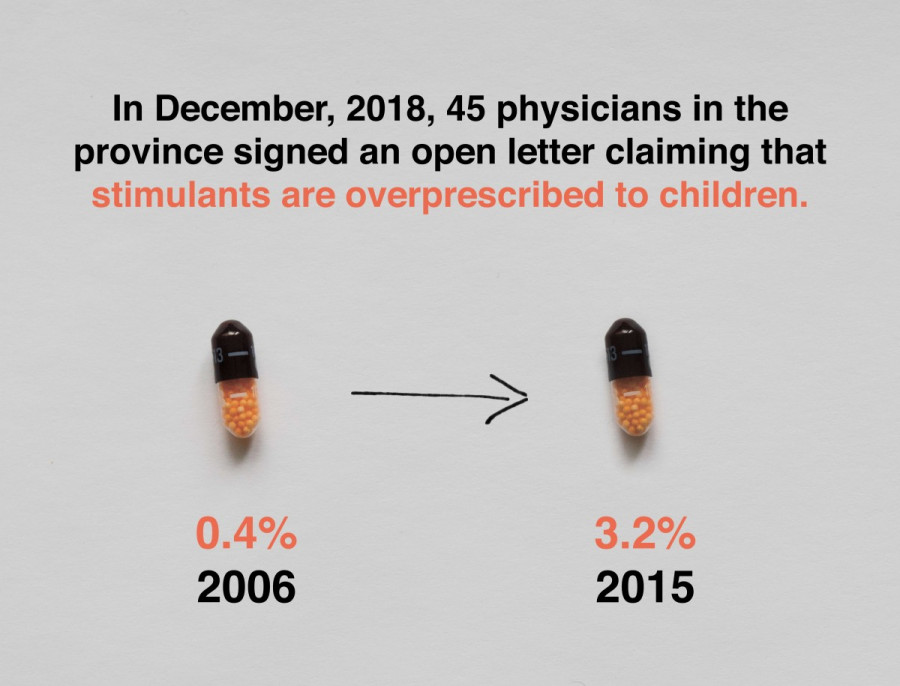

In Quebec, in 2017, stimulants for ADHD were prescribed at three times the rate of any other province. Recently, 45 physicians in the province signed an open letter claiming that stimulants are overprescribed to children, adolescents and young adults. The letter states that from 2006 to 2015 in Quebec, prescriptions for patients between the ages 18 to 25 jumped from 0.4 per cent to 3.2 per cent.

Michel Perron, CEO of the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, told the CTV that most students get the drug from someone they know who has a prescription.

“It’s all about who you know,” said Miller. “I have friends [with ADHD] who are willing to give me some of their Adderall when they don’t need it.”

She said her friends will sell it to her for $5 a pill, while her dealer sells for $10 a pill.

Daniel Grey* found himself on the other side of this interaction, giving Concerta to his friends for free.

Grey is a prescribed user of Concerta (a brand name stimulant similar to Ritalin) at Carleton University. Grey talked about his experience with attention deficit disorder. He was prescribed Concerta and has taken it “on-and-off” since his diagnosis three years ago.

He said he takes one 36-milligram pill per day, and he has been using the prescribed dose for three months. He said, “I kind of feel like I don’t need it,” and admits that he’s scared to be reliant on the drug.

Grey lives in residence and says he’s given it away. “All of my friends know I have Concerta,” said Grey. He said he’s found that one or two of his friends will ask if he has any pills to spare during exam time.

A 2012 study concluded that “MAS [a brand name for Adderall] has no more than small effects on cognition in healthy young adults [who do not have ADHD], although users may perceive the drug as enhancing their cognition.” In separate trials where patients received either Adderall, a placebo, or nothing at all, they nevertheless performed the same.

Miller said, “Adderall doesn’t make me smarter, it just makes me focused.”

In users who do not have ADHD, stimulants like Adderall and Ritalin provide a boost in focus and energy, decrease appetite, and induce feelings of euphoria.

In a Facebook post on Spotted Concordia, an anonymous student wrote, “Yesterday morning at 7 a.m. I popped four pills of Adderall to study and haven’t slept or eaten since. Any recommendations to make me pass out?”

Repeated abuse of stimulants may lead to side effects such as mood changes, increased blood pressure, aggression, anxiety and heart palpitations.

A 2008 study on rats showed that stimulants may change the genetic makeup of the brain: after eight months of methylphenidate (Ritalin) treatment, rats had diminished ability in their dopamine receptors. The Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse identifies paranoia and hostility as long term effects of abusing stimulants.

In 2015, Health Canada warned that all stimulants used to treat ADHD may be linked to increased suicidal thoughts and behaviours. ABC News and The New York Times have reported on how the suicides of Kyle Craig, 2010, in Nashville and Richard Fee, 2011, in Virginia were linked to ADHD medicine.

The Richard Scott Fee Foundation was established after his suicide to raise awareness about the misdiagnosis of ADHD and the dangers that come with stimulant abuse.

“Periods of high stress [in academics] can lead students to turn to substances. That’s why we need more and more support systems for students who abuse drugs.”

— Sylvia Kairouz

Miller thinks it is overlooked that Adderall has serious effects on your health and that it needs to be treated more seriously as an addictive substance. In the days following Miller doing stimulants, she has to remind herself that she can’t use Adderall for everything.

“It’s easy to fall into that trap if you’re not careful,” she said.

Miller uses Adderall or Vyvanse to study, finish papers and do readings. She said, “It’s as simple as I’m doing work and I don’t think about little things like, ‘I need to check Instagram,’ or ‘I need to text my mom.’”

Miller said she uses stimulants because she procrastinates, doesn’t manage her time well, and her work tends to pile up at the last minute.

She says on Adderall she’s less anxious about due dates. “I abuse it—I know it’s a problem, I’m not proud of it.”

Sylvia Kairouz, head of the Lifestyle and Addiction Research Lab at Concordia and associate professor in the psychology department, said it’s just part of student culture to experiment with substances.

Kairouz refers to overmedicalization as a potential factor in the abuse of stimulants. “It’s very clear that ease of access to a substance is just one more incentive to consume.”

Kairouz said when dealing with the issue of stimulant abuse, we need to reevaluate the promotion of “performance and success culture.”

“I don’t think people realize how damaging it is to always be told that you need to be the next Elon Musk” said Miller. “This whole culture. You think it’s positive, but it’s really damaging. You think everybody is having productive days.”

“I feel like a failure because I didn’t wake up at 4 a.m. and get all my work done—I feel like shit,” Miller recalled breaking down over the phone with her mom telling her, “It’s impossible to be the best that you can be every single day.”

Risks associated with long term stimulant use include psychosis, and some accounts of suicidal thoughts in children have been reported.

While the number of children diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed stimulants has increased, physicians in Quebec have only just started bringing their concerns to light. Sociologists like Kairouz believe there is a link between success culture and abuse of stimulants.

Kairouz said, “Periods of high stress [in academics] can lead students to turn to substances.”

“That’s why we need more and more support systems for students who abuse drugs.”

In March, the Concordia Student Union published “Addictions Peer Support Programs on University Campuses,” a report addressing Concordia’s lack of resources for recovering addicts. With suggestions from the Taskforce for Students in Recovery, made up of people “touched by addiction,” the union announced the implementation of peer support systems on campus.

CSU Student Life Coordinator Michèle Sandiford said peer support groups will counter the long wait times for mental health support at the Access Centre for Students with Disabilities. “There are institutional barriers in accessing treatment, things like long wait times will discourage students from seeking out help.”

“[The peer support system] gives students the opportunity to get in right away, and start their journey of recovery,” she continued.The report defines addiction as repeated involvement and reliance on a substance or activity “because that activity may be pleasurable.” Sandiford conceded that this definition may be narrow, as it does not encompass stimulant abuse. Kairouz says stimulant abuse is complicated because students often don’t use them for pleasure, and rather for academics.

Sandiford said, “People have a preconceived notion of what addiction may look like.” She understands that some people may abuse drugs while not seeking pleasure, and thinks it may make it harder for stimulant addicts to seek support.

“We understand that it is not comprehensive and people dealing with addiction may need a multi-pronged approach,” said Sandiford.

As a recovering addict, Sandiford said, “Peer support has been critical in my recovery. It allowed me to build strong support groups and have accountability to people who care about my wellbeing.”

Sandiford confirmed that a space has been found for the groups to meet. Students struggling with addiction could have these resources as soon as April, but Sandiford says is may be more feasible to stretch the launch until September.

Students who think they may be struggling with addiction can speak with a bilingual, trained counselor 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, toll-free everywhere in Quebec: 1-800-265-2626 and in the Montreal area: 514-527-2626.

.WEB_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)