A Universal Language

What Can Esperanto Do For You?

The world is home to about 6,500 spoken languages.

But what if there was one spoken by everyone?

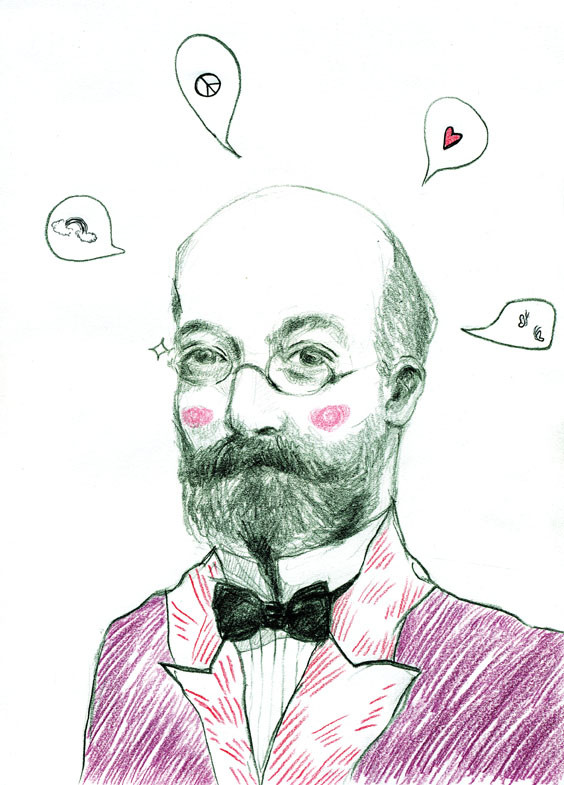

This was the dream of 19th century Polish linguist Ludwik Lazarus Zamenhof. A native of Bialystok, Poland, Zamenhof’s hometown was equally home to Polish, Belarusian, Russian and German communities, prompting a language gap between residents.

It is this language gap that spurred Zamenhof’s belief that a universal language could be the key to achieving world peace. In 1887 he took it upon himself to create one: Esperanto— which translates to “the one who hopes.”

“Esperanto is what we call a constructed language, that many people learn as a hobby,” said Morgan Sonderegger, an assistant professor of linguistics at McGill University. “A constructed language is one that someone or a group of people made up all the rules and vocabulary for; [one] that didn’t arise as a natural language [such as] English or Mandarin.”

The majority of Esperanto’s roots are Latin, though some vocabulary is taken from modern languages such as English, German, Polish, Russian and French.

Since Esperanto’s first world congress organized in France in 1905, it has been recognized as an alternate international language by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Today, statistics show that there are between 100,000 and 2 million active or fluent Esperanto speakers worldwide. The International Academy of Sciences in San Marino, Italy, has even made Esperanto its current language of instruction.

“It all depends on the person’s capacities, but Esperanto is fairly easy to learn, even more for someone who speaks French or Spanish,” says Zdravka Metz, who co-founded the Société québécoise d’espéranto in 1982.

“You can learn it in less than a month if you put effort into it.”

If you already speak English, the most widely used language in the world, there may seem to be little point in learning Esperanto. Metz says that isn’t the case.

“Here in North America, English and French are enough for you to make yourself understood, but if you travel in Europe, English isn’t enough,” says Metz, who grew up in Croatia, about 30 kilometres away from the Hungarian border.

“If you’re a scientist, a mathematician or a computer engineer and you want to share information with your peers worldwide, you won’t translate your work in each main language; it’s way more useful to communicate in Esperanto,” she added.

But could Esperanto actually replace English as the world’s universal language?

“Maybe, I don’t know,” Metz admitted. “Because when you learn Esperanto, you won’t necessarily find a career [in the language].”

For Metz, the role of Esperanto today isn’t so much achieving world peace, as its creator originally hoped it would, as much as simply facilitating international communication.

“I don’t think it’s essential for everyone to learn Esperanto, but it all depends on what you want to do in your life and how you want to use it to your own advantage,” said Metz. “If you like travelling once in a while, it can be useful to learn some of it, but if you want to work in the business world, for example, it might be useful for you to master it so can deal with people all over the world.”

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)