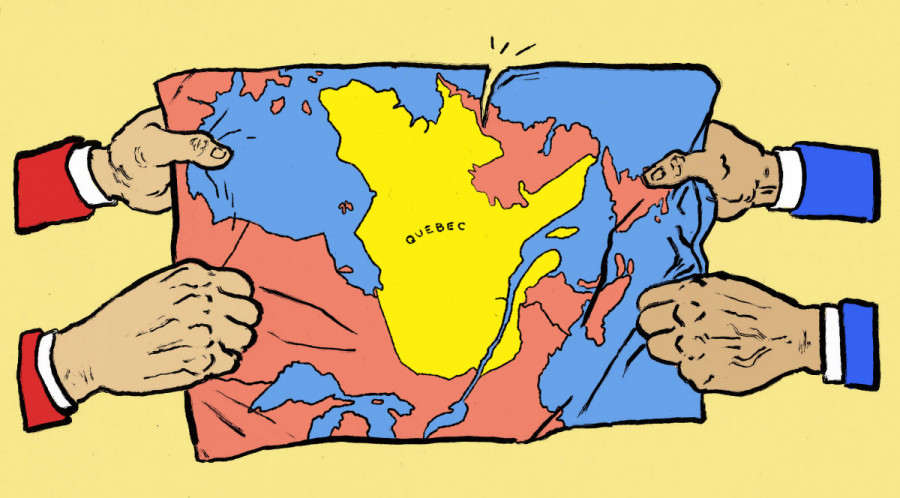

A fractured state: Quebec’s 1995 referendum

The after-effects of the nearly country-fracturing decision can still be felt 25 years on

“We won the referendum, but we were divided as a society,” said Dominique Anglade, leader of the Quebec Liberal Party. “Families [were] divided. Friends [were] divided.”

Anglade was 21 at the time and involved with the No campaign at Polytechnique Montréal’s student society. Anglade watched the results from her home with her sister and some friends though some in her usual circle—Yes supporters—were absent.

Some of her friendships had grown tense, consumed by disagreements about the upcoming vote on Quebec’s future. “Before things get worse, you say let’s not talk for a while,” she recalled. “We’ll talk after the referendum.”

Meanwhile, then 13-year-old Sol Zanetti, current member of the Quebec National Assembly and Québec Solidaire’s spokesperson for the issue of sovereignty, was also engaging with the possibility of a divided country.

“[My father] was not a separatist and did not see the need for Quebec independence. He voted No. I, like all 13-year-old boys, felt that my dad was right. At the time I even participated in a history class debate on independence, and I was the spokesperson for the No camp,” Zanetti laughed. “It’s funny how things change.”

October 30 will mark 25 years since the last time Quebecers were asked to go to the polls and choose between what former Quebec premier Jean Lesage distinguished between la patrie and le pays. Ninety-three per cent of registered voters showed up, making it the highest turnout in Canadian history.

Although the sovereigntists led for most of the tally, Canada squeaked through the night by a single percentage point. For federalists, the result was a wake-up call about the fragile state of the confederation. For sovereigntists, the fight lives on.

Constitutional fallout and the campaign

Tensions between la belle province and the English-speaking provinces were growing after the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords failed. If they had succeeded, they would have reintegrated Quebec into the constitution in exchange for greater provincial powers and recognition as a “distinct society.”

“Had Meech [Lake] gone through, we would not have gone through Charlottetown,” Anglade said. “Most likely, we wouldn’t have gone through a referendum.”

Jacques Parizeau’s Parti Québécois rose to power in September 1994 but the premier had no intention of being a provincial politician and announced that Quebec would hold a referendum on the issue of Quebec sovereignty within a year.

To some, the ballot question drafted by future Parti-Québécois leader, Jean-François Lisée, was confusing.

To others, it was forthright. “Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement signed on 12 June 1995?"

The Yes campaign got off to a rocky start, but when the Bloc Québécois’s charismatic Lucien Bouchard joined their ranks, support for a sovereign Quebec soared. Federalist politicians did not know how to counter Bouchard’s rising popularity.

The plot thickened in December 1995 when Bouchard was struck by flesh-eating disease. The Bloc opposition leader survived the close encounter, but the rare disease claimed his leg.

Many suspected he would not return to politics, but three months later he limped back into parliament, steadying his gait with a cane. He received a standing ovation, even from Reform Party leader Preston Manning who offered praise in staccato French.

“We come back to his chamber with a renewed hunger for life,” Bouchard stood up and said in the House of Commons. “Time is so precious and there is so much left to do.”

While questions were being raised about Chrétien's ability to continue to lead Canada in event of a Yes victory, frustrated Minister of Fisheries, Brian Tobin, organized a Unity rally to inspire Quebecers to choose Canada.

On Oct. 27, amid accusations of unlawful campaign expenditures, over 100,000 Canadians from across the country were bused to Place du Canada in a show of force.

Two days before the referendum, a Leger & Leger poll conducted for the Globe and Mail called the vote a “toss-up” with the Yes side leading by 3.8 per cent.

“Canadians awakened the morning of October 31 to an intact country, but the dominant mood everywhere—even in Quebec—was one of gnawing uncertainty and morbid introspection.”

— Robert Wright in The Night Canada Stood Still

Referendum rematch

On the night of the vote thousands of hopeful sovereigntists flocked to the Palais des congrès while federalists, fearing embarrassment, watched the results come in from the much humbler Métropolis.

The Madeline Islands were first to report. The results showed strong support for sovereignty, a worrying sign for prime minister Jean Chrétien who was anxiously watching the results trickle in at 24 Sussex Drive.

As the Yes votes streamed in, prime minister Chrétien’s advisor, Eddie Goldenberg, was already drafting a defeat speech. “Mr. Chrétien was absolutely clear that he was going to say that this was not a vote for separation,” he said on Jacqueline Corkery’s Breaking Point. “We’re going to have to work together to make changes that will make everybody comfortable to stay in Canada but under no circumstances am I going to allow the breakup of this country.”

However, when Montreal started reporting its results, the Yes lead slipped. By 10:20 p.m., the CBC reported that the result was clear. The vote had split along linguistic lines and Quebeckers had chosen Canada by 54,288 votes.

Amid blue and white fleur-de-lys banners, a fiery Parizeau tried to rile up his supporters for the next fight. “We will have our country. It is true that we were beaten, but by what? By money and the ethnic vote.” He shook his head and the crowd cheered.

The CBC panel, which included a 36-year-old Stephen Harper, had strong words for Parizeau, none more critical than Bob Rae.

The then-Premier of Ontario had “never seen a more disgraceful public performance,” he said. “It was demagoguery as its most awful. It was an attack on everybody of a different language or race other than that of Mr. Parizeau. Perhaps alcohol may be an explanation.”

“Quebec divided,” read Le Devoir’s cover page. “A majority of francophones have said YES.” Parizeau resigned less than 24 hours later.

National introspection

“Canadians awakened the morning of October 31 to an intact country,” Robert Wright wrote in The Night Canada Stood Still. “But the dominant mood everywhere, even in Quebec, was one of gnawing uncertainty and morbid introspection.”

“It was not like it was 20 per cent in favour of a yes,” said Anglade. “It was 49.4. There was definitely something that needed to be repaired. There’s no question in my mind.”

The Liberal leader believes that progress has been made in implementing some of the measures that were originally included in the Meech Lake Accord.

In 2006, the Harper government recognized Quebec as a nation within Canada and granted the province greater authority over its immigration and judiciary systems. “But there’s a number of things that we need to keep working on with the federal government to make sure that Quebec has all the levers to go and develop.”

Future of Quebec sovereignty

“Some bridges were destroyed that needed to be rebuilt,” Zanetti said about Parizeau’s money and ethnic vote outburst. Since the referendum, the Parti Québécois has “antagonized many new Quebecers on the issue of independence” by appealing to the right on issues of reasonable accommodation, he said.

Despite diminished support for sovereigntist parties, Zanetti is committed to an independent Quebec that meets the challenges of 2020. “Québec Solidaire is resolutely inclusive, committed against racism and committed to issues that were less omnipresent in 95 like the environment and climate change,” he said.

If elected, Québec Solidaire would push for a referendum in a first mandate, he said, whereas the Parti Québécois has “abandoned independence a little bit.”

Differences with the rest of the country are irreconcilable, he said. “Our interests are structurally opposed because [Canada] is a petrol-state. Canada wants to be able to pass pipelines underneath us. They want to keep Quebec because Quebec controls the St. Lawrence waterway and it could cut off Canadian oil producers.”

However, not everyone agrees that Québec Solidaire is truly committed to the separatist cause. “Québec Solidaire is not a sovereigntist party,” said Guy Lachapelle, professor of political science at Concordia University. “How can you be a sovereigntist party and support the NDP at the federal elections? Their goal is to take over the PQ, but it’s NDP Quebec.” The Parti Québécois is the only true sovereigntist party, he explained

“The climate was very, very different then,” Lachapelle continued. “There’s no appetite now for sovereignty, but still the numbers are there.” Current support hovers around 30 per cent, he said—around the same level when Parizeau’s Parti Québécois rose to power. “There will be another referendum at some point. When will the next [one] be? I don’t know.”

Parizeau died in 2015 and Bouchard has retired from political life. The crisis of Quebec declaring itself a sovereign state was narrowly averted a quarter-century ago, but Quebec still has not formally signed the Canadian constitution.

Separatist embers still linger in Quebec’s National Assembly, waiting for right political winds to make the dividing lines between Canada’s two solitudes an international border.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_900_642_90_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)