A New Migrant Detention Centre Is Being Built in Laval as Quebec Hardens Stance on Immigration

The Canadian Border Service Agency’s Migration Detention Centre Is Set to Open by 2021

While the world reacted in horror to the Trump administration’s widespread use of detention and child separations as a deterrent to asylum seekers on its southern border last year, Canada has been quietly employing similar practices for quite some time.

While new legislation tabled by the Coalition Avenir Québec government could put many migrants and asylum seekers in a furthered state of legal precarity here in Quebec, a new migrant detention facility, scheduled to be opened in 2021, is being constructed in Laval by the Canada Border Services Agency.

The cavernous lobby of the Guy-Favreau complex on René-Lévesque Blvd. is familiar to anyone who has had to navigate the complicated, costly, and often opaque Canadian immigration process. In the Service Canada offices located there, posters of smiling, helpful faces loom over migrant hopefuls as they wait in line to submit their forms and documentation.

This is the national identity that Canada wants to project to the world: We are multicultural, inclusive, and tolerant—a tapestry of the intertwined experiences of our ancestors, who fled forgotten hardships and prejudices now somewhat extinguished by the passage of time.

We tend to consider ourselves a little kinder, gentler, and more sensible than our southern neighbours. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said to CNN in 2016, “The fact is, Canadians understand that immigration, that people fleeing for their lives, that people wanting to build a better life for themselves and their kids is what created Canada.”

Every year thousands of migrants end up indefinitely incarcerated within a network of detention facilities and prisons strewn across the country, often after having been detained without criminal charges or a trial. Some have remained incarcerated in a state of legal limbo for years on end.

During the 2016-2017 fiscal year, 6,251 migrants in Canada were detained and spent a total of 131,617 days in detention, according to CBSA statistics. These numbers are not an anomaly. Nearly 36,000 people have been detained between 2012 and 2017. At least 16 migrants have died in detention in Canada since the year 2000.

Child separation and the detention of minors, though not as widespread as in the U.S., are not unheard of.

According to 2017 CBSA statistics, the most recent ones available, 66 minors were detained in a currently existing detention centre running out of Laval. 31 minors were also housed there, meaning they had no grounds for detention but remained with parents to prevent family separations.

“In the exceptional cases where a minor’s parent [or] legal guardian may be subject to detention, the CBSA will work with the parent or legal guardian and child welfare authorities to assess [the] best interests of the child and the best way forward,” said CBSA spokesperson Jayden Robertson.

This often forces parents to either subject their child to incarceration at their side, or to surrender them to foster care.

Take the case of Glory Anawa, brought to light by the CBC, who was attempting to claim refugee status in Canada on the grounds that she was fleeing forced female circumcision in her home village in Cameroon. When she arrived, a few months pregnant, at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport in 2013, her claim was denied and she was put in detention.

Her son, Alpha Anawa, came into the world at a detention centre. Alpha’s first words were “radio check,” the phrase used by their guards to signal a shift change in the centre in which they were forced to live. Anawa remained there for nearly three years before being deported back to Cameroon.

Stories like that of her and her son are not unusual. Last year in Canada, an average of 333 people sat in detention every day.

Within the past few years, there have been a series of detainee hunger strikes and detainee deaths—along with pressure from support networks outside the centres—that forced the then-incoming Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Ralph Goodale to address the state of the migrant detention system in 2016.

“In my first few months as minister responsible for CBSA, I have certainly heard the concerns about immigration detention, and I’ve studied those concerns with great care,” Goodale told the CBC. “The government is anxious to address the weaknesses that exist and to do better.”

In response to deteriorating conditions and overcrowding in detention facilities, the Liberal government launched the National Immigration Detention Framework. The NIDF’s goals are, “To create a better, fairer immigration detention system that supports the humane and dignified treatment of individuals while protecting public safety” through greater transparency and improved “risk assessment” of detainees.

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act states migrants to Canada should only be detained after all alternatives to detention have been explored and when grounds for detention exist, primarily if the person poses a flight risk or is a danger to the public.

$138 million in federal funding over a period of five years was earmarked to meet NIDF objectives. The money will go towards improvements to immigration holding centres and the increased implementation of “alternatives to detention” technologies, including the use of electronic monitors and biometric voice-recognition check-in systems.

But the majority of the budget is going to the construction of two new dedicated detention centres, one of which is currently under construction in Laval.

Sam Hoffman is a spokesperson for Ni Frontières, Ni Prisons, an organization dedicated to halting the construction of the new Laval centre. The group has started targeting the companies involved in the construction process, in an attempt to dissuade them from participating.

They started with the Montreal-based architectural firm Lemay, who have won over $5 million in contracts to design the Laval facility, along with the Quebec City based architecture Group A.

“Lemay is profiting off of putting migrants into prison by designing a new migrant prison for the federal government,” said Hoffman.

The blueprints for the Laval site mention that, “The general design principle is to use long life cycle materials in interesting ways, to bring a human scale to otherwise unforgiving environments.”

“Heavy timber or engineering wood will be used throughout in order to showcase a warm and homey feeling.”

Since people in detention centres aren’t charged under the criminal code, but on immigration grounds, Robertson mentioned the new centre is not a prison.

“It is a facility built to accommodate individuals whose risk level necessitates CBSA surveillance, in order to ensure the agency is able to effectively carry out its mandate.”

But critics like Hoffman feel the facility’s designs betray the underlying character of the NIDF budget, which he characterized as an expensive, disingenuous redirection which achieves only incremental change while attempting to divert public attention away from the larger issue of migrant detention itself.

“It doesn’t matter how nice you make a prison. Migrant detention just shouldn’t be happening,” said Hoffman. “The government is hoping that it can succeed in masking this violence, both of the prison itself, but also of the deportation process that it is subjecting these people to.”

Lemay declined to comment on their role in the project based on conditions set by what Lemay Spokesperson Annie Gagnier described as “their contractual agreement with their client.”

“The design of the CBSA immigration holding centres were undertaken in a manner that ensures Canada’s alignment with international obligations and standards for immigration detention,” said Robertson. “It is premised on the basis that immigration detention is administrative in nature and not punitive.”

But whether a deportee is placed in an administrative or punitive holding cell before being ejected from Canada, Hoffman pointed out that migration is often driven by uncontrollable circumstances like war, poverty and persecution. Migrants deported to their countries of origin can return to the difficult or dangerous circumstances that drove them to leave in the first place.

“If my grandparents had come to this country with these kinds of policies in place, they would have been hunted down by the CBSA, thrown into a migrant prison, and then deported back to Europe to probably die at the hands of anti-Semitism,” said Hoffman. “The fact that this is happening today and no-one seems to think that it’s a problem is atrocious.”

“If my grandparents had come to this country with these kinds of policies in place, they would have been hunted down by the CBSA, thrown into a migrant prison, and then deported back to Europe to probably die at the hands of anti-Semitism.”

— Sam Hoffman

Raúl came to Canada from Cuba. A pseudonym has been granted to protect him and his family from persecution.

“I’m here in Canada under a refugee protection claim,” Raúl told The Link. “I’ve been here for a year and a half. It’s kind of hard, honestly, because I have no idea how my future is going to be.”

The last major battle of the Cuban Revolution was fought in 1958 in Santa Clara, Raúl’s home town. The revolution, in its infancy, strived to improve the quality of life for Cuba’s poorest through land redistribution and a wave of progressive social reforms.

But after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Cuba entered what Fidel Castro dubbed a “Special Period in a Time of Peace.” During that period, Cuba was suddenly deprived of crucial economic aid from the U.S.S.R. and plunged into grave economic crisis characterized by scarcity, fuel shortages, and starvation, which lasted for years and marred the psyche of an entire generation.

“At that time I was a teenager,” Raúl said. “My parents had a really hard time feeding us. One of my brothers suffered from malnutrition. There’s a lot of things that aren’t nice to talk about, but this was my experience. It was a bad time.”

While the economic situation in Cuba has marginally improved since then, most Cubans, who survive on rations and an average wage of $25 USD a month, still struggle to get by.

“The main problem is food,” Raúl said.

Long-standing U.S.-led sanctions have also exacerbated Cuba’s economic woes, pushing the island nation to the brink of collapse. The recent crisis in Venezuela, a key economic partner of Cuba, has threatened to further destabilize the Cuban economy, which depends heavily on economic assistance from the oil-rich nation.

Raúl said his situation is further complicated by the repressive nature of the Cuban political system and its utilization of state employment as leverage to force compliance to authoritarian censorship laws and practices.

“I used to have a band,” Raúl explained, “We wrote some lyrics about problems in society and with the government, and obviously that is not allowed. The first problem I had was that I lost my job. Nobody told me it was for this reason, but I know it was. I was then informed by the government that my mother, who is a lawyer and works for them, could have problems at her job too. This is normal in Cuba.”

Today, Raúl is living in Quebec and has applied for permanent residency. So far, he said he has no news regarding the outcome of his case.

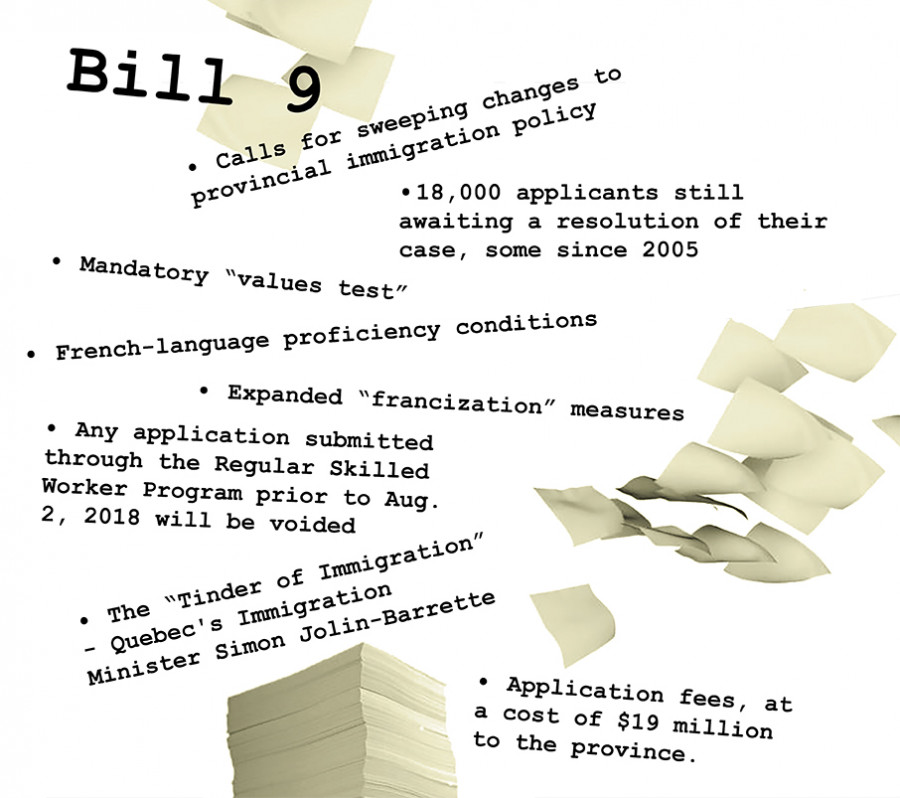

But the recent announcement of new legislation which could cause his application to be thrown out has caused Raúl to worry about his future here. That new legislation is Bill 9, the CAQ’s proposed amendment to the Quebec Immigration Act.

The bill, tabled on Feb. 7, calls for sweeping changes to provincial immigration policy. Immigrants would undergo a mandatory test to prove that their values align with the province’s and demonstrate their proficiency in French. The bill also states that any application submitted through the Regular Skilled Worker Program prior to Aug. 2, 2018 will be voided.

The bill also stipulates that the roughly 18,000 applicants still awaiting a resolution of their cases, will subsequently be reimbursed for their application fees, at a total cost of $19 million to the province.

These applicants would then have to re-apply for their Quebec selection certificate under new, more restrictive criteria, through a new system which Quebec’s Immigration Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette described as the “Tinder of immigration” likening it to the popular dating app.

“After all of this happening, it’s a big concern that’s always in my mind,” Raúl told The Link. “If you try to leave Cuba, they know. You leave everything behind. If I have to go back, I go back to a country where I have nothing.”

Raúl is not alone in his concern. The application purge would apply not only to the 18,000 main applicants, but their families as well, ultimately affecting over 50,000 people currently awaiting processing.

While Legault proposed slashing immigration levels by 20 per cent, he recently clarified, “We’d take more French people, and Europeans as well,” while speaking to Le Devoir during a visit to France earlier this year.

“We do not want to keep too many people who do not accept our language [and] our values,” Legault later added in an interview with Radio-Canada.

Bill 9 has been critiqued as being nationalist and exclusive, granting the party praise by far-right anti-immigrant group La Meute, whom CAQ leader François Legault has tried to distance himself from. The CAQ’s immigration policies have also won acceptance by France’s Le front national leader Marine Le Pen.

Bill 9 has faced significant pushback, both in Quebec and in Ottawa. An injunction filed by the Association québécoise des avocats et avocates en droit de l’immigration has ensured the application purge will stay on hold until the bill has cleared the review process in the National Assembly and is signed into law.

The federal government shut down the tests and conditions proposed by Bill 9, saying it overstepped Quebec’s jurisdiction within the federal immigration system.

Meanwhile, the 2019 federal budget, tabled by the Liberals on March 19, has allocated an additional $1.18 billion to be spent over the next five years to expedite the apprehension, processing, detention, and deportation of irregular asylum seekers arriving from the U.S., whose numbers spiked in 2018 in response to the Trump administration.

For the time being, Raúl tries to stay positive. “If I get denied again, it’s back to Cuba I guess. Then I try to save money, go back and try to survive as best I can.”

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)