What Do You Do When The Sport You Love is Taken From You?

How Severe Sports Injuries Affected my Playing Career—And My Mental Health

Growing up Canadian, I did what most kids do at some point in their lives: I took up hockey.

At this point, it’s so ingrained in society it borders on cliche. However, being part of a Greek family, my attention was drawn in another direction: soccer. A passion for the sport spawned early and was based heavily on my grandfather and his love for the game.

From then on, I played soccer year-round and learned everything I could about being a defender. I played at different levels and made it all the way to provincial championships.

Spending so much time working and getting better takes a lot of commitment and even more passion. Luckily I had an excess of both and was getting ready to play at the CEGEP level. So what do you do when something you love so much and dedicate so much time to is taken?

Injuries—when one plays high-level sports year-round—are more than common, but I had a pretty good track record for most of my life. The longest I had been out was a few weeks with a broken foot.

Bruises and scrapes were part of the territory, so imagine my surprise when the biggest injury of my life came from one of the most mundane settings imaginable: last-period high school gym class.

After jumping to block a shot in handball, one of my classmates landed on me while I was falling, hitting me in the perfect spot on my left knee.

“Pop.”

It was followed by a deafening silence that lasted all of one second and a distinct feeling that took over my entire body.

“Something is very wrong,” I thought to myself.

And then it hit me. This wave of pain was unlike anything I had ever felt in my life. I couldn’t pinpoint any specific part of my knee—everything was on fire. At the hospital, X-rays showed nothing wrong, but it took an orthopedic surgeon 30 seconds of testing to find out what was wrong: a torn anterior cruciate ligament.

One MRI later and it was confirmed. I had torn not one, but three different parts of my knee: my ACL, my MCL, and my meniscus.

The average timeframe for recovering from ACL surgery ranges from eight to 12 months, so you could imagine my excitement when I was cleared to return to the pitch after six. I was ready to go by September 2015. With both the winter soccer and hockey seasons around the corner, it was almost as if I had never left.

However, life is rarely so simple. Not even a month into my return, I was forced back to square one. While playing flag football in gym class, my foot slipped and I dislocated my right knee cap. When it popped back into place, it sliced through my ACL, my MCL, my meniscus, and my patellar tendon.

Four deafening pops—like when knuckles crack—echoed across the field.

“Please, God. Let this be a broken leg.”

What is What?

ACL: The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the key ligaments that help stabilize your knee joint. The ACL connects your thigh bone (femur) to your shinbone (tibia).

MCL: The medial collateral ligament’s (MCL) main function is to prevent the leg from extending too far inward, but it also helps keep the knee stable and allows it to rotate.

Meniscus: The meniscus is a piece of cartilage that provides a cushion between your thighbone (femur) and shinbone (tibia).

Patellar Tendon: The patellar ligament not only helps keep the kneecap in its proper position but also assists in the bending of the leg at the knee. It is essentially responsible for the motion of a leg extension.

That was the only thought going through my head, along with the dread of knowing how familiar the pain felt. A broken leg heals, but a knee injury meant at least another year before getting back to normal. The complexity of the four separate tears meant I would need not one, but two surgeries and at least another year and a half of physiotherapy. Something I was not willing, or mentally capable of doing.

After my surgery the first time around, I couldn’t wait to get back. I watched what I ate, did the exercises prescribed by my physiotherapists, and was able to start running after less than two months—way ahead of schedule. I was in a great headspace and couldn’t wait to get back to the action.

However, the situation with my right knee was a lot more complicated. It took my physiotherapist less than five minutes to realize this injury was much worse than my first. It was too swollen to do any accurate tests, but he could tell there were at least four different things wrong. After I got the news that I would need two surgeries to keep playing soccer or even high-level hockey, I essentially gave up.

Patellar reconstruction patients are a high priority, meaning I was on the operating table within the week. But this time the recovery process felt different. I felt cheated and gave in to the idea of giving up soccer. I felt cheated out of playing the sport I love and—through no fault of my own—would have to once again endure the most emotionally and physically gruelling challenge I’ve ever taken on.

I was sick and tired and I just wanted to give up.

So that’s exactly what I did.

I was going to be off my feet for six weeks as opposed to the two week period my first surgery demanded, and I dove head-first into a lengthy depressive episode. I didn’t care about what I ate, I cut myself off from my friends, I neglected my recovery, and my grades fell off a cliff. I still feel those repercussions today with a right leg that is significantly weaker than my left. The muscles in my thigh atrophied and I didn’t have the will or the confidence to do anything about it.

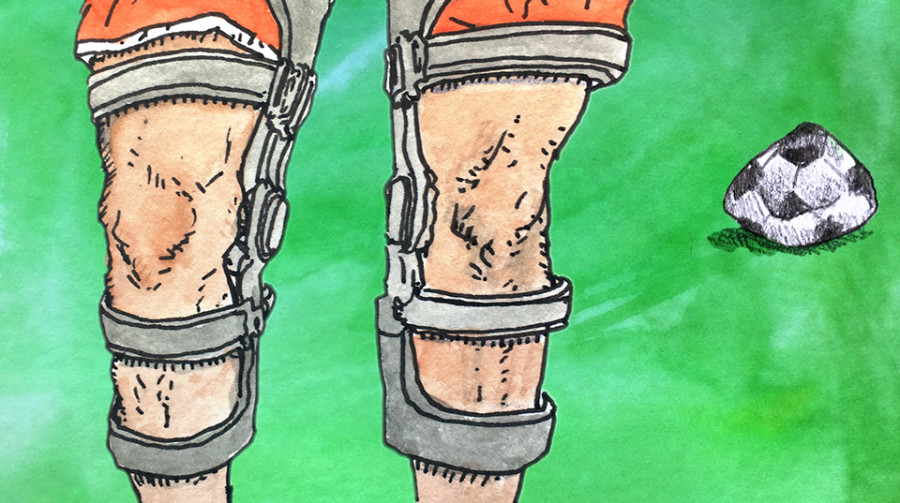

There was a brief overlap where I had to wear two knee braces at the same time and—while there were a couple funny “bionic man” jokes from those around me—I felt utterly useless. There was an overwhelming feeling that I was a charity case. I was still invited to events with both my soccer and hockey teams but they felt at times like pity invites. I had missed out on almost two years-worth of bonding, inside jokes, and shared memories because of this injury and was never able to get that back.

Truth be told, it’s an extremely isolating feeling. Being in my physiotherapists’ office is normally a very supportive environment where a lot of people are going through the same struggle as you. That felt very comforting for the recovery from my first surgery.

But it was harder to find the motivation for the second one when you have the worst injury in the room by a country mile. You become accustomed to more bad news than good and, regardless of how good my physiotherapists were—Tom and Guillaume, I love you with all my heart—it’s tough if not impossible to get down.

I can no longer play soccer at any level. Forget competitive, forget returning to a regional level—let alone provincial. I need another surgery if I want to do anything other than kick a ball around with some friends. I still get to play hockey with some of my oldest friends but the hole this string of injuries left cannot be filled by only that.

This is normally the part where I go “it was a rough few months, but I’m better now.” While that may technically be the case and I’m not as low as I was after my second operation, long-term injury—especially career-ending ones—is not something one just magically gets over. This is not a story about how I conquered all this shit and rose above it.

This is a story about how something very dear to me was taken. And how the recovery process will last so much longer than any physiotherapy—it’s still ongoing almost five years later.

4_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

2web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)