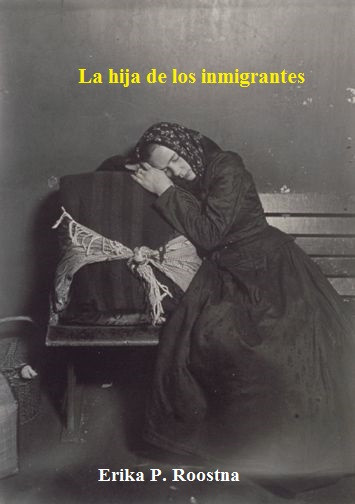

“The Immigrants’ Daughter” Recalls Her Experience

Erika Roostna Reflects on Immigration from Venezuela to Canada in Upcoming Book

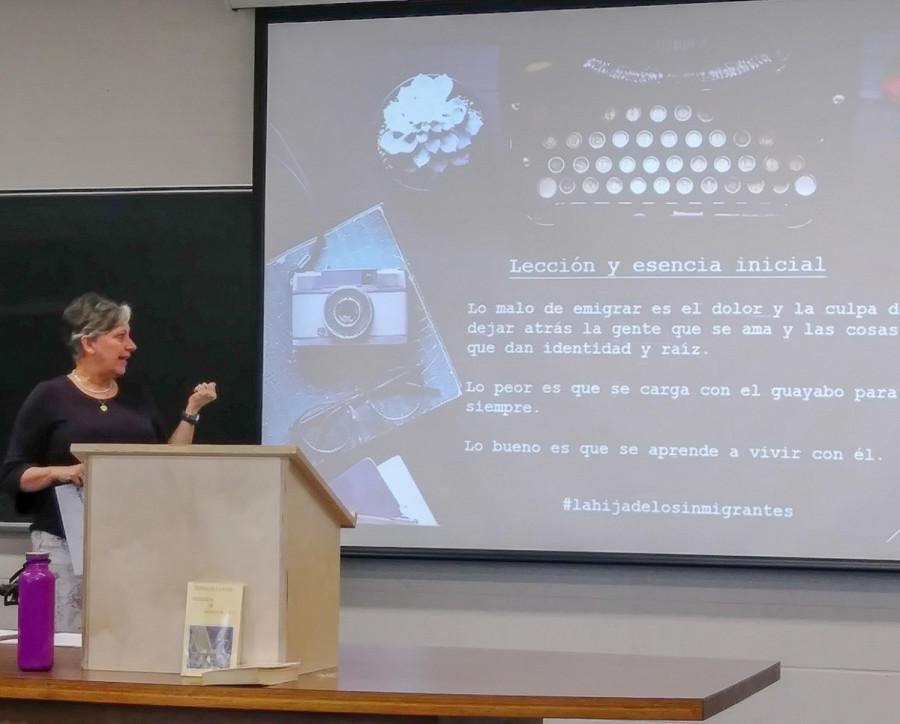

Erika Roostna touched the hearts of a number of Concordia students, with a preview of her upcoming book, La Hija de Los Inmigrantes (The Immigrants’ Daughter).

Detailed and nostalgic, the book is a collection of memoirs, about her personal experience as an immigrant, transitioning from a Venezuelan fugitive, to an at-peace Canadian citizen.

The conference was hosted in the Hall building on Feb. 28 by Concordia’s Linguistics professor Lady Rojas Benavente. Students were encouraged to listen to Roostna speak of her personal experience as an immigrant.

Benavente hoped that her students would be inspired enough to one day write about their own experiences, and how their own parents felt towards the changes in their lives.

Roostna is not a writer by profession—she is an engineer. However, she has recently taken an interest in writing her deepest thoughts, and boastfully sharing her roots as a Venezuelan immigrant in Canada.

Although born in Venezuela, Roostna is of European descent. She calls herself a “daughter of immigrants” because both of her parents found solace in a country that wasn’t their own.

“My father, Arne Roostna, is Estonian, and my mother, Elizabeth Javornik, is Slovenian,” Roostna said. Between 1945 and 1950, her parents lived as war refugees in Austria, before settling in Venezuela.

While Venezuela seemed like a safe choice at the time, it soon became a hostile environment for Roostna, forcing her to seek refuge elsewhere.

“For us, at the time, it was not economical, we lived a perfect life,” Roostna said. “But we were seeing things that happened with my parents during the war. There were a lot of similarities with what they had lived, and what we were starting to live.”

The political instability in Venezuela began to frighten Roostna, as she realized the danger her family was put in just by walking down the streets. “We didn’t have a declared war in Venezuela, but there was a lot of insecurity,” she explained.

Before Nicolas Maduro, Hugo Chavez was the president from 1999 until his death in 2013. Venezuela had been dabbling with a socialist government for a while and Chavez’s handling of the national oil company. Riots have since taken place, and Roostna has participated in a number of them.

“I’ve had my share of tear-gas,” she chuckled. “Without my kids, though, it was my husband and I.”

Two years prior to her immigration to Canada, a landmark incident took place in Caracas in April 2002, called “Puente de Llaguno,” otherwise known as the Llaguno overpass. When the Confederación de Trabajadores de Venezuela (a national federation of trade unions) called for a coup-d’etat, a million Venezuelans marched against Hugo Chavez on April 11, 2002.

In response to the strike, gunmen stood atop of the Llaguno bridge and began shooting the rioters. Luckily, Roostna was not present at the riots that day, but the massacre had still made its mark.

It is as Celia Rojas Viger; PhD in Anthropology poetically said, “Poverty, and war are the two main reasons for immigration.” And war was Roostna’s ultimate push.

“It’s the tyranny,” she said. “Those regimes that stomp on people, on human rights, that’s what needs to change. And hopefully it will soon.”

Roostna regretfully stated that she has not gone back to Venezuela since. She does not own a Venezuelan passport, and cannot enter the country without one.

“The Venezuelan authorities are not giving you a passport as a punishment,” she says. “The borders are not closed, but they are. Because they’re [not giving people passports] as a way of closing the borders.”

When it comes to the publicity surrounding the Venezuelan crisis, Roostna believes that social media does a good job at raising awareness. Despite that, it’s still not enough.

“Us human beings are so overwhelmed with everything going on in the world that we tend to ignore or run away from certain things,” she stated. “You go on Facebook, you watch a sad video, you react in a sad way, and then you move on.”

Since 2004, Roostna has settled in a quiet neighborhood in Bolton, Toronto with her husband, Noel, and her two children, Sabine and Noel Arne.

When asked if she ever felt like a stranger in North America, she happily shook her head.

“Canada is my home. As I said, the process of dreaming of Canada has made me comfortable here,” she stated. “No country is perfect. Some things here still bug me, but compared to what we were living in Venezuela, when I first came here, this was like, heaven.”

Her family, however, did not share her enthusiasm at first.

“My daughter hated me,” Roostna confessed. “When we left, we were in the process of the Quinceañera, so she had to leave her life and all of her friends behind. And I did not know how to explain to her that this was the only way.”

Erika Roostna’s book, La Hija de Los Inmigrantes, will be published in May. It’ll be published first in Spanish, but Roostna is not averse to translating her work.

“Living in a place like Canada, and having friends that do translations, I’ll hopefully have it in other languages,” she said.