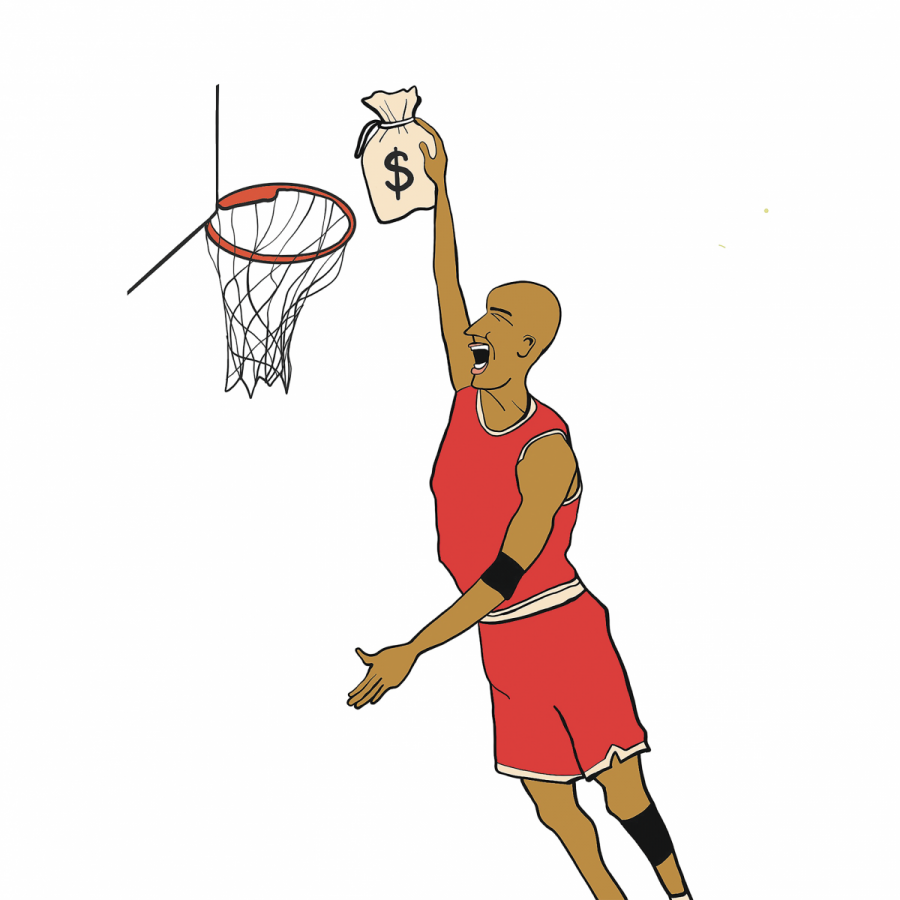

California Ruling Makes Way for Student-Athletes to Get Paid

Students to be Paid for Use of Their Names and Images as of 2023

In late September, the State of California ruled that student-athletes in the National Collegiate Athletic Association should be paid for the use of their names, images, and likeness.

According to the report Madness Inc., by Senator Chris Murphy, only $936 million U.S. was spent on student aid, with $1.2 billion U.S. spent on coaches’ salaries. The revenue for U.S. College sports programs? $14.1 billion U.S. for the 2017 season.

So, why are so many people against paying students for their work?

“Student-athletes are not employees” is the argument used most often by people like Donald Remy, the NCAA chief legal officer. But they are chosen for their skill, much like employees are. These young men and women are expected to be at the top of their game at all times and not have off days.

Over the last few years, there have been instances of players, like University of Connecticut basketball player Shabazz Napier who said in a 2014 locker room interview “there’s hungry nights and I’m not able to eat.”

Others, like Richard Sherman, who at a pre-Super Bowl press conference in 2015, discussed how he barely had time to go to class or do classwork.

“Show me how you would schedule your classes when you can’t schedule classes from 2-to-6 o’clock on any given day,” he said. Show me how you’re going to get all your work done when after you get out at 7:30 or so, you’ve got a test the next day, you’re dead tired from practice and you still have to study just as hard as everybody else every day and get all the same work done.”

On top of that, students sign a rule book of 428 pages that tells them everything they can and cannot do.

Mark Emmert, the current NCAA president, said students are compensated through education in a 2011 interview with the PBS show ‘Frontline’.

The NCAA themselves state on their recruiting fact sheet that less than two percent of students make it to the professional level. Some get injured and can no longer play, while others don’t make it in the pros. Meanwhile, the NCAA has made millions off of sponsorships and brand deals on the backs of these students.

So, to have the state of California say that the students should be able to be compensated for the use of their names and likenesses being used is a great place to start, though I’m not sure if it goes far enough.

While these players could potentially make millions off of deals with brands and companies, the NCAA would still make billions of dollars annually. Coaches themselves would still be able to pursue endorsement with various companies, and the players who arguably do the work could not—until now.

Many people see this as students getting what’s owed to them for being used to promote products. The rules need to allow for students not only to be paid but to be protected if they get injured and to allow them to continue to study if the injury means they can no longer play, at the very least.

Education should be emphasized, but that also means students should have time to take care of themselves. They should have time to attend class and study and have the resources to help them balance their school and work life. Students should be able to balance their sports and social life without having to worry about being dropped from a team.

There are many concerned about reckless spending and that because they’re young, they won’t know how to spend all this money and will end up in trouble somehow. Yet that worry seems to disappear for those who do make it to the professional level.

If student-athletes start getting paid, that could mean that they’re better able to care for themselves and their families. If someone is benefiting from the skills of a student, why can’t the student benefit too?

The bill is set to take effect in 2023 and is bound to be full of controversy until then.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)