The Controversial Topic of Free Education

Weighing Both Sides of the Spectrum of How Free Education Can Be Obtainable

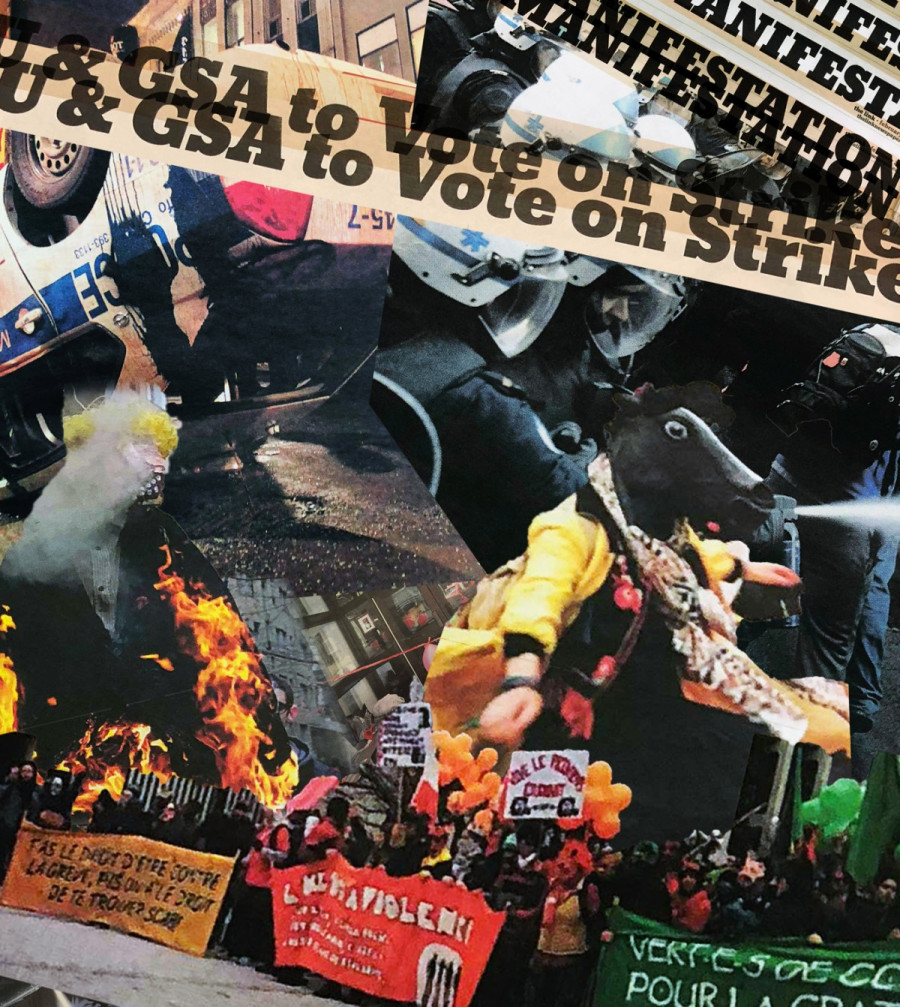

Red squares, protest signs and chanting filled the Montreal streets for many spring and summer nights in 2012, as thousands upon thousands filled the streets to protest the projected tuition hikes.

The Liberal government, at the time led by Jean Charest, imposed tuition hikes of $1,625 over five years for university students. This initiated a series of protests, some nights drawing in crowds of thousands, with the peak of the protest in March of 2012 drawing in 200,000 people to protest within one day. By the end of May, the Quebec justice system was overwhelmed with arrests, more than 2,500 students having been arrested. Many more were arrested later that season.

The fire of inspiration that drove many to the streets is still alive today for some, as free education is still an important topic, addressed when the government suggests or imposes tuition hikes. There hasn’t been a movement as influential since 2012, however, activism has remained strong at Concordia, as 16 students underwent a tribunal process for tuition hikes for protesting in 2015. This drew a campaign hosted by the Concordia Student Union to dispute these charges in 2016.

The topic of free education in Quebec has recently been brought to light again during the provincial elections. In the debate on student issues held at Concordia on Sept. 21, inviting one party member from six provincial parties in the running for leadership to discuss issues related to students, the Coalition Avenir Québec representative in the Sainte Rose district, Christopher Skeete said the CAQ does not endorse free tuition, however, he said their party will not impose tuition hikes.

The CAQ and Skeete did not respond for further comment before the deadline of this article.

Free education may not be a reality under the ruling of the CAQ, but Québec Solidaire, a democratic, socialist and sovereigntist party, is still fighting for free education.

Co-spokesperson of Québec Solidaire Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois is a former spokesperson for Coalition large de l’Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante, a now defunct coalition of students opposed to the tuition hike. In 2012, Nadeau-Dubois fought alongside with thousands and thousands of both students and community members to oppose and resist the tuition hike.

CLASSE intended to fight for free tuition to be available within the province of Quebec by 2016. While their hopes of free education did not succeed, Nadeau-Dubois continues the fight further than the borders of Montreal, but within the realm of Quebec provincial politics.

Coverage of Maple Spring student protests:CLASSE’s aspirations didn’t come true, but this large mobilization was inspiring for some, including Concordia Student Union Finance Coordinator John Hutton, who attended Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia at the time. Hutton said this is where he saw anti-austerity activism happening in Quebec. “In that case [of the Maple Spring protests] Quebec [was] showing some national leadership, and we should certainly keep pushing further,” said Hutton.

“Education is not something that is a privilege, it is a right for everybody, education is something that gives you the tools to understand the world around you,” said Hutton. “It’s not just something that individually benefits me, everyone around me benefits—someone else getting a medicine degree benefits me.”

Everyone should have access to it, Hutton continued, because it not only empowers people, but the current average student debt in Canada is approximately $30,000 upon graduation. Recent data provided by Statistics Canada in 2017 show that the average debt of Canadian graduates is $26,000.

More than 70 per cent of all jobs require some form of post-secondary education, according to Universities Canada. “It’s not just something that empowers individuals, it’s something that people need just to meet the basic requirements to feed yourself and survive in society,” said Hutton.

CSU External Affairs and Mobilization Coordinator Camille Thompson said her opinion on education changed when she was told in 2012 that education is a way for people to climb the social ladder. “The more you increase the price of it, the more you make sure that people who do not have the revenue cannot access those higher social ladders,” Thompson said. She said the cost of tuition and hiking these prices is increasing the division between the rich and the poor.

CSU supports free education for all, as stated so within their official positions book. The student union has had a history of mobilizing. Notable events in recent years are the CSU voting to strike during the Maple Spring protests in 2012, and CSU hosting multiple anti-austerity campaigns—including Concordia Against Tribunals—in support of students undergoing tribunals and facing sanctions, as a result of protesting professors hosting classes within a department that voted to go on strike.

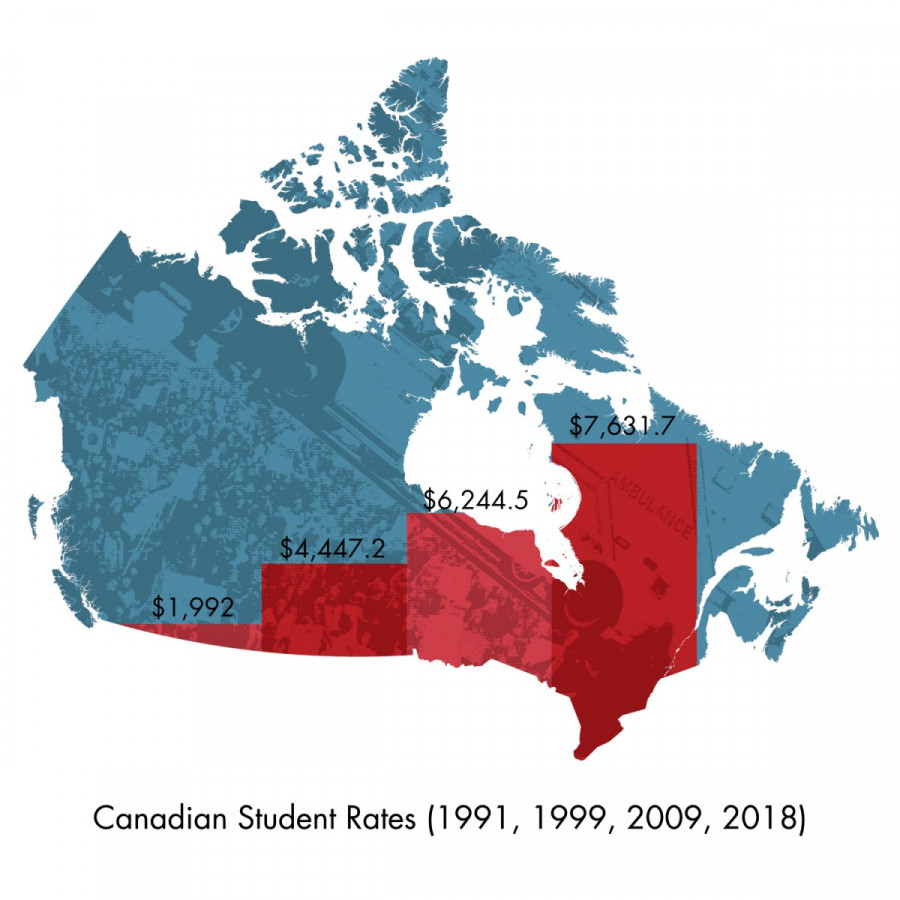

Hutton said tuition has risen for all of Canada, since the federal government, under the leadership of Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien and finance minister Paul Martin decided to make $12 billion in cuts towards university education and health transfers between 1994 and 1998.

“It used to be that [provinces] had a lot of federal funding, but now you have this idea that education is a provincial responsibility only,” said Hutton. He said once the federal government made cuts, all of the financial burden was placed on provincial governments. “They couldn’t take on that load, so they put it onto students,” said Hutton. “That’s when you start to see tuition fees soaring in Canada, that’s when you start to see student debt rising in Canada.”

Instead of Quebec raising fees, Hutton said, we should be seeing the federal government re-invest in education. “We need to have something like the Canada Health Act, where federal transfers are provided to the provinces for education.”

Nadeau-Dubois told The Link education should not be about how much you or your parents have, but education should be accessible for everyone and the revenue you have should not be the determining factor of who should go or not to university.

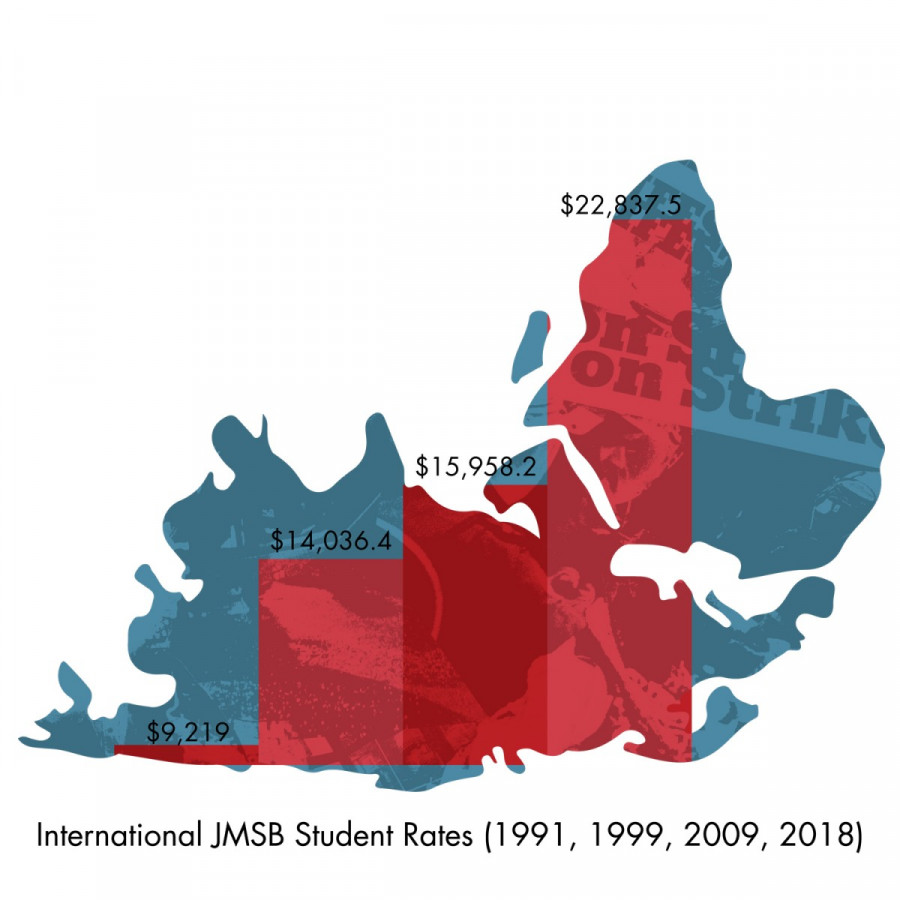

Québec Solidaire’s platform for free education intends to fund schooling for all—from preschool to the PhD level. Out of all Canadian provinces, Quebec has the lowest tuition with prices ranging depending on chosen study. Tuition for Quebec residents ranges from $3,775, with out-of-province students paying $8,675 and $19,802 for international students. These statistics are based on Concordia’s rates, which include health and compulsory fees, and account for 15 credits taken for both fall and winter semester, excluding summer.

“Education is not something that is a privilege, it is a right for everybody, education is something that gives you the tools to understand the world around you.”

— John Hutton, Concordia Student Union Finance Coordinator

Moshe Lander, lecturer in the economics department at Concordia, is not in favour for free education and doesn’t think it’s a beneficial idea. He believes that only some programs should be free, ones that he says are beneficial to all, such as positions in the medical industry.

He said when he worked in Alberta he often heard on the radio the need for nurses. Lander said in a case like this, free education should be given to nurses to motivate people to work in this field. As for who he thinks should pay for a nursing degree, Lander said it should be the institution benefitting from nurses, which are hospitals.

“Hospitals should be willing to put up thousands of dollars in essentially scholarships to anybody who wants to go study, because they’ll be the benefit of it when you come out on the other side with a nursing degree, [the hospital] can immediately hire you,” said Lander.

Nadeau-Dubois said Québec Solidaire has a similar intention, but towards all programs. The party proposes to collect revenue to put towards free education by taxing large corporations, not small businesses, but large companies with more than 500 employees. “Those are companies that can pay their fair share of taxes,” said Nadeau-Dubois.

Similar to Lander’s proposal for free education for nurses, Nadeau-Dubois said these corporations will benefit from having an educated workforce.

“In the last years, governments in Quebec have systematically lowered the taxes on big corporations,” said Nadeau-Dubois. He said that’s less than what most Quebecers pay.

If elected in the future, the party intends to raise taxes on these corporations from 11.9 per cent to 14.5 per cent. Nadeau-Dubois said this proposal is not even half of what it was in the early 2000s, so they are not asking for so much. He said the taxing of corporations will result in $2 billion of revenue to put towards education. The cost of higher education for Quebec residents, out of province and international students would cost $1.3 billion, according to independent think tank Montreal Economic Institute.

Lander fears if taxes are raised on corporations, they will leave to other provinces and cities and feels this will impact the economy by pushing large businesses away. “How much of that big business is going to resent having to pay taxes, that they say we’re going to relocate […] we’re out of here,” said Lander. “You need to have a better economic plan than just the politics of rail against the rich and speak for the poor,” said Lander.

However, Nadeau-Dubois said he doesn’t understand that hypothesis. “I think the facts contradict that argument, when you look at the countries where education is free […] those countries have one of the most prosperous economies,” he said.

Nadeau-Dubois said the argument seems short sighted, as “employers and corporations, they take advantage a lot of the fact that they do business in a educated society and that they can have an educated workforce.”

“When you look at places like the United States, where the tuition fees are the highest in the world, it does not make the United States a model in terms of having a stable and strong job market,” he continued.

Lander proposed instead of free education, certain industries could fund programs within the field of their business, or follow a similar model to Australia, where students can receive loans and pay their tuition back if they make over a certain annual salary.

James McIntosh, a professor within Concordia’s economics department, echoed a similar sentiment as Lander. He believes more money should be put into bursaries, or that students should be able to take out loans for tuition and pay them back if they make over a certain salary. He said that the government has enough money to pay for education.

On average in Quebec, those with a high school diploma will have payed about $200 thousand in taxes over 45 years, and those with a university degree will have payed $400 thousand within the same timeframe, said MacIntosh.

“The state gets $2 thousand in tax revenue for every university degree that produces, to say that we can’t have free education because it’s so costly—the state’s actually doing very well tax revenue wise for having a university system,” he said.

“That is something that we would not accept in healthcare or for high school, why does that work for [post-secondary] education?” argued Hutton. “We already have a system where people who make higher incomes fund education, it’s called the income tax system.”

Hutton added this ensures there’s redistribution from the rich to the poor, so everybody can access public services. “You don’t need to create strange bureaucratic schemes where the government measures your income after graduation,” said Hutton. “The income tax system is a much more effective way of doing that, we can have free tuition under it too.”

However, McIntosh believes that low fees tend to encourage those to go to university who shouldn’t be in university, who are not as committed and don’t work as hard. “That’s expensive, because the state has to provide places for them in university and the state pays the university on a per capita basis, so the more students a university has the more money the university gets,” said McIntosh. “You want everybody to go to university if they deserve academically to go to university.”

Nadeau-Dubois said he noticed irony within the Liberal’s campaign during the recent provincial election with the Liberal’s stating they would abolish tuition fees for CEGEP programs that had a lack of employees in the workforce the diploma prepared them for, in order to support more enrolment. “It was a very interesting announcement because it really reveals […] that free tuition is a good way to encourage people to go and educate themselves,” Nadeau-Dubois said.

He added that it’s ironic to see a government that, only a few years ago, said tuition fees have no impact on post-secondary enrolment are now saying they will provide free tuition for certain diplomas to encourage students to apply. “It really shows that we were right when we were saying all along that the price of education actually has a real impact on the decision to go and study or not,” he said.

McIntosh believes that those with financial burdens due to economic or income disadvantage should utilize bursary programs and other methods of financial support.

Dipjyoti Majumdar, an associate professor in Concordia’s economics department, had similar feelings to Nadeau-Dubois. Majumdar not only thinks free education is beneficial for students, but it is beneficial to the overall society at large. He said in countries like Germany—where education is free—the quality of life is better, considering the average lifespan, level of wealth, access to food, in comparison to Quebec.

Majumdar agrees with McIntosh, and believes there needs to be a merit-based system. “If education is free here there will need to be a selection procedure to get students into different streams [of study],” said Majumdar.

Mikayla Harris, the research and pedagogy coordinator for Association pour la voix étudiante au Québec, a student association which operates on the provincial level, said protest is the strongest form of resisting tuition hikes and fighting for free education, to make our voices heard at the governmental level. Harris said obtaining free tuition and opposing hikes is most beneficial when protests are hosted through student unions. Harris said action must be taken through student organizations, because they can stand united as a voice to put pressure on the schools deans and directors, who will then put pressure on the government.

Hutton feels free education can be obtained. She said this issue is moving into the mainstream, such as one of the three largest parties, the New Democratic Party of Canada, being in favour of free education.

“When I first got involved in my undergraduate, making the pitch to students that we can reduce tuition fees, by even 10 per cent, I was [titled] as a radical,” Hutton said. “Now we’re seeing in places like the United States, the U.K., huge movements are arising around free tuition—we’re seeing it in Canada too.”

Thompson is not as hopeful as Hutton, considering the political climate, “but I think that each fight counts,” said Thompson. “I’m hoping that one day education will be accessible to all,” she said.

Despite the argument varying from both sides, the fight for free tuition will last as long as the mobilization within student bodies remains strong and parties like Québec Solidaire continue to fight at the provincial level.

_600_375_90_s_c1.JPG)