Trials and Triumphs of Black Canadians

A People’s History of Canada Column

For Black Canadians, racial prejudice has always been a complex issue.

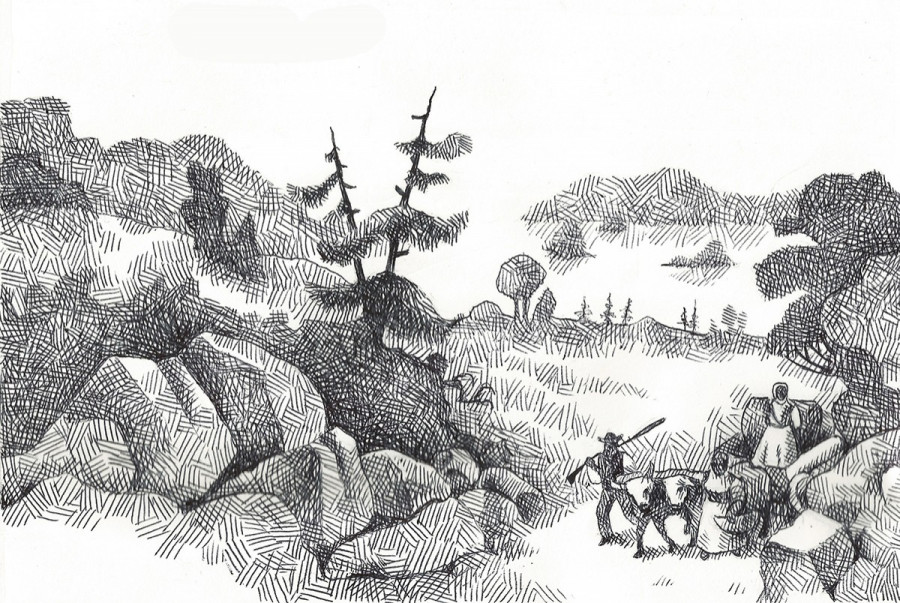

Before the American civil war, Canada represented—even if only on the surface—a safe haven for Blacks fleeing the bitter realities of slave life. However, while the shelter of the Canadian flag afforded legal protection, Blacks would soon find that “going north” did not mean leaving racial oppression behind in the slave labor camps of the Deep South. Rather, like a shadow, it would follow them right across the border.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Black population in Canada was less than 18,000. However, this marked the first time that white Canadians began to become aware—and fearful—of the fact that there was a growing and increasingly visible minority of Blacks in Canada. White Canadians who were at first tolerant or indifferent to migrants became progressively hostile.

Shortly after slavery became illegal in the U.S., Blacks looking to carve out a life in the Canadian West had to contend with the pseudo-anthropology and pseudo-science of racial theories of Black inferiority that comprised mainstream academic, cultural, and social thought. Having already gripped the imagination of whites in Europe, Britain, and the United States, it was now spilling over into Canada.

Post-civil war “theatre” productions known as minstrel shows involved skits in which men—often white—painted in blackface portrayed Blacks as dim-witted, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky characters. It quickly became a popular Canadian cultural form.

In Halifax in 1884, Academy Hall boasted a full house to see Callender’s Colored Minstrel. A well-known cartoonist, Henri Julien, was praised for his charming piece “By-Town Coons” in which well-known Canadian politicians were painted in blackface.

“It is a well-known fact”, read one Ontario publication, “that every different race of people emits a different smell, it being an especial characteristic of the Negro.”

In Nova Scotia, The Windsor Mail concluded that Black “peculiarities… [are] so abnormal that… he sinks to the level of the animal,” due to their supposed proclivity for gin, fried liver, outlandish religion, witchcraft, sex, and song.

Unfortunately, as far as racial discrimination goes, we are not short on examples. Not only language, literature, and theatre but also science and history were deployed to conjure powerful mythologies of that pleasure-loving, lustful, unreliable, foul-smelling, and primitive character within the Canadian imagination known as “the Negro.”

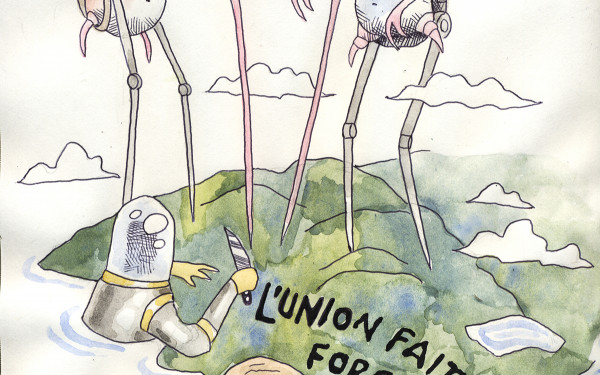

Though facing stiff opposition from Canadian society, many Black migrants were not deterred. In March 1911, a party of two hundred Blacks came to the border station at Emerson, Manitoba hoping to be reunited with their relatives who had already made it across the border. Though they were unfairly subjected to harsh examinations, the border officials found that none of them could be legally prevented from gaining admission. They all had three times more than the required $100 amount, impeccable health, the required documentation, and written attestation of their character.

Fearing the potential of even more qualified Black migrants, the Secretary of the Edmonton Board, in a swift act of legislation, barred entry to all Blacks and a head tax on all Negroes was proposed. The Winnipeg Board of Trade, having seen eye to eye with the Edmonton Board, endorsed the head tax, and concluded—dishonestly—that those Blacks had “not proved themselves satisfactory as farmers, thrifty as settlers, or desirable [as] neighbors” despite the obvious fact that they had not been given the chance to harvest a single crop. In spite of their resilience, the obstacles for hopeful Black migrants were proving to be many.

During an investigation shortly after, the American Consul-General at Winnipeg learned that the Commissioner of Immigration for Western Canada had been bribing the medical inspector at Emerson with a sum for every failed physical examination of a Black person.

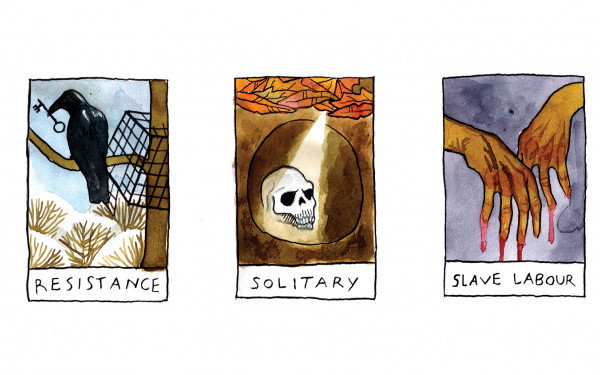

The same year, the Great Northern Railway informed all its employees that Blacks would not be allowed into Canada. When WWI broke out, Blacks faced similar opposition enlisting in the army. The commander of the 10th Overseas Battalion wrote to the Minister of Militia and Defense, Colonel Sam Hughes, that, having turned away nineteen Blacks in Saint John: “I have been fortunate to have secured a very fine class of recruits, and I did not think it was fair to these men that they should have to mingle with negroes.”

Getting across the border was not the only feat. Integration into Canadian social life also had its challenges. In 1924, the Edmonton City Commissioner closed public swimming pools and parks to Blacks. In Colchester, Ontario, police kept strict patrols to prevent Blacks from frequenting beaches or parks. In 1915 in Saint John, Black residents were forbidden from going to any restaurants or theatres. The list goes on.

“In spite of their resilience, the obstacles for hopeful Black migrants were proving to be many.”

Nevertheless, many Blacks managed to rise above pervasive economic and social exclusion. Some Blacks arriving in Toronto in the 19th century such as Wilson Ruffin Abbott became successful businessmen and active members of political life.

Born to a free mother in Richmond, Virginia, Abbott left home at 15 in search for work. Though initially apprenticed as a carpenter, he moved to Mobile, Alabama to open a grocery store with his young wife, Ellen Toyer, whom he met during his travels. Having been driven from town by whites who pillaged their store, they moved to Toronto where Abbott became an up-and-coming real estate broker.

In 1871, Abbott, having spent 36 years in Canada, owned forty-two houses, five vacant lots, and a warehouse. His financial success allowed him to purchase the freedom of fugitive slaves, to keep his wife’s sister as a housekeeper, and to remain actively engaged in community life. He helped found the Colored Wesleyan Methodist Church of Toronto, hoping that it would create a sense of community and solidarity among Canadian Blacks. Having been elected to the Toronto City Council, he also served on the Reform Central Committee. In addition, his wife also organized the Queen Victoria Benevolent Society in 1840 to help poor Black women.

Five years before Abbott died in 1876, he saw his son, Anderson Ruffin, graduate from the University of Toronto and become the first Canadian-born black to receive a license in medicine. Two years later, Ruffin was appointed a surgeon in the Northern army. When the war ended, he opened his own practice in Chatham, Ontario, and became president of the Wilberforce Educational Institute from 1873 until 1880.

Writing for various local papers, he spoke out against the Canadian segregated school system. A man with a towering intellect, he composed a great variety of manuscripts—some eventually becoming public lectures. His writing spanned numerous areas of study, exploring topics like medicine, history, Darwinism, poetry, and education. Ruffin, like his father before him, was committed to life in Canada.

Upon the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, he composed the poem “Neath the Crown and Maple Leaf, an Afro-Canadian Elegy” which was published in The Colored American Magazine. It captured the pride Ruffin felt for being Black and Canadian.

His ardent belief that Canadian Blacks could succeed in a hostile Canadian social climate motivated him to condemn the creation of a new all-negro school in Saint John, support armed resistance of Blacks in the south, and begin his project of mapping out a broad history of negro activity in Canada in an attempt to arouse greater racial pride. His historic project pointed to other Black Canadian trailblazers who embodied the kind of character and perseverance that Ruffin and his father epitomized.

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)