Journalism, the mouthpiece of the elite

Barriers for non-upper class journalists may spell the end of an already declining industry

Each year, The Canadian Association of Journalists releases a diversity survey. This survey lists demographic data of various Canadian newsrooms. Absent from this report, however, is one of the most underrepresented groups in modern journalism: the working class.

Class is also not listed in the Review of Journalism’s 2023 diversity report. In fact, class in Canadian newsrooms is so understudied that relevant data for this article was difficult to find. This, in itself, is an issue.

But class is recorded in the United Kingdom’s journalism diversity report. According to the report commissioned by the National Council for the Training of Journalists, 72 per cent of U.K. journalists had at least one parent in one of the three highest occupational groups. Among the broader British workforce, the number is only 44 per cent. This means U.K. journalists are twice as likely to be from higher-class backgrounds.

This is also an issue in the United States, some argue. Batya Ungar-Sargon’s Bad News calls out the American media for being elitist. And Nikki Usher’s News for the Rich, White, and Blue: How Place and Power Distort American Journalism argues that modern media is produced, consumed, and catered to the rich and the white.

There is little reason to believe Canada is much better, but as there are few surveys that study class in Canadian journalism, it is difficult to know just how pervasive this issue is.

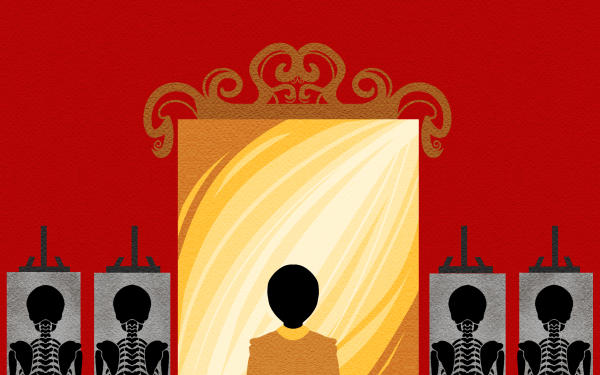

The elitism starts at the barred gate blocking the entrance to the industry. Journalism is built on connections and networking; breaking in as a newcomer is a difficult task. The decline of print media—and the rise of social media—has made this entrance even harder, as ad revenue has taken a nosedive, resulting in smaller newsrooms and fewer jobs. Just this year, the Canadian journalism industry has seen hundreds of layoffs at mainstream outlets, such as the National Post and Groupe TVA. Corporations’ responses to Bill C-18 have also resulted in media being ousted from major social media platforms.

For many, journalism school is one of the only doors into this declining industry. However, j-school is expensive and time-consuming. Canadian j-school tuition rates range from $5,000 per year to tens of thousands per year. As with most higher education, those who attend tend to be those who are fortunate enough to have parental support, or those who can afford the tuition and lost wages from time not working. To top it off, internships, which are the foot in the door for many, are often unpaid.

A career in journalism is not often lucrative, either, which makes it difficult to repay student debt. According to Statistics Canada, the median hourly rate for journalists in Quebec was $32 per hour last year. Glassdoor Jobs places the average income for Canadian journalists at $57,605. Coupled with the rising cost of living, the housing crisis, as well as the inconsistent hours and the lack of benefits for new and freelance journalists, a career in journalism is near impossible to pursue without money.

From the start, journalism has a filter which makes it easier for those of higher class to succeed. They can better afford j-school. They’re also more likely to have connections within the industry, as they’re more likely to be from a similar social class. This is an issue that needs addressing for a number of reasons. Most prominent for journalism, however, is that the under-representation of people of different backgrounds results in an echo chamber, and a breeding ground for nepotism.

Journalism is a public service. Its purpose is to inform the public, unbiasedly and without agenda, and to shed light on issues, people and events of public interest. It cannot perform this function well if it actively disadvantages a section of the population it purports to serve. It is, of course, impossible for journalism to be completely unbiased. However, diversity of thought and experience are essential to providing coverage that is as well-rounded as possible. Without it, the industry only serves as an elitist mouthpiece, detached from the public they’re writing for.

The result: the public stops reading. Journalism becomes written by the elite, read by the elite, and eventually, written for the elite. And the industry, without broader public engagement, continues to decline.

Some might say this argument is insider-baseball; that all industries which require higher education are less accessible to those of lower socioeconomic status. This is true. Those with more money have more options in most circumstances. However, classism in journalism is a uniquely pressing issue, as it directly impacts the function of the newsroom and has the potential to become detrimental to it.

Public trust in the media is already trending down. According to Reuters Institute’s 2022 Digital Report, only 42 per cent of Canadian respondents regularly trust their news, with younger Canadians being less trusting than older Canadians. That’s less than half of the population, and that number is not likely to be re-established without systemic change.

So, what can be done to fix the problem? Well, for starters, the industry needs to scrutinize the recruitment process, all the way down to j-school admissions. Journalism needs to ground itself in the people it serves—including working class people. And that starts with hiring them.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 8, published January 16, 2024.

_600_375_s_c1.png)