From The River to the Sea returns after being censored

La Sala Rossa hosts the reprogramming of Jocelyne Saab’s films

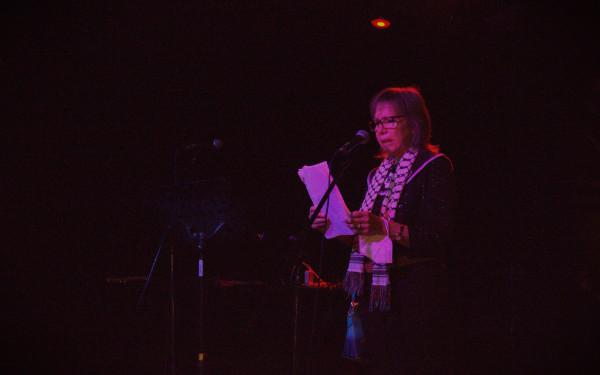

On Jan.17, La Sala Rossa welcomed the reprogramming of projections organized by the fundraiser screening series From the River to the Sea with open arms.

Comprising Regards Palestiniens, the coalition presenting the series also included Hors champ, Dhakira Collective, Feminist Media Studio, Zoom out, Le Sémaphore, Cinema Politica, Main Film, Cinéma public, and Palestiniens et juifs unis.

Instead of a ticket, the fundraising event requested proof of donation—minimum $15—to one of the following organizations: Medical Aid for Palestinians, Palestine Children Relief Society, or Palestinian Medical Relief Society.

Presented by Hors Champ and Regards Palestiniens, hundreds of people gathered, some sitting on stacked black folding chairs, some standing by the bar behind. With a warm and antique decor, la Sala Rossa is a beautiful room part of a historic building built by members of Montreal’s left-wing of the Jewish community in 1932.

La Sala Rossa gladly reprogrammed films censored by Cinéma Du Parc as they were supposed to take place in their venue on Nov. 6. According to a member of Regards Palestiniens, Cinéma Du Parc canceled the screening and engaged in censorship due to unfounded claims of security concerns based on racial prejudice and stereotyping.

“It's with complete shock and horror that we find ourselves having to waste our energy over conversations about slogans and semantics, where we've been witnessing and grieving indiscriminate and violent mass execution and maiming and the injuring of Palestinian men, women, and children,” said one member who wished to remain anonymous.

The long history of cultural organizations trying to silence solidarity with Palestine was cited in the presentation of documentary films produced by Jocelyne Saab. The event projected four of her works: “Palestinian Women,” “The Front of Refusal,” “The Boat of Exile,” and “Beirut, My City.”

After the screenings, a discussion was conducted. The moderators were Claudia Polledri, a history and cinematography studies lecturer as well as a specialist in Lebanese cinema and photography, as well as filmmaker Muhammad Nour ElKhairy. Polledri gave the audience broader context on Saab’s life journey, and background as a filmmaker, highlighting journalist Mathilde Rouxel’s crucial role in preserving and restoring Saab's films. Rouxel is the first writer to conduct a monographic study dedicated to Saab and her works from 1970 to 2015.

Saab, born in 1948, was a Franco-Lebanese journalist, documentarist, filmmaker, and a strong activist to the Palestinian community. Her exploration of the Palestinian cause began during visits to Palestinian camps in Lebanon with colleague Elias Sanbar.

“Archives are the most reliable piece of information that people could use to get educated on the subject because the media won’t talk about it.” — Annette Diallo

Between 1975 and 1982, Saab's films, subject to censorship, depicted theft, dispossession, apartheid, and violence during the Lebanese civil war. These documentaries focused on Palestinian women, exploring challenges in refugee life, adaptation, and classism. The films also showcased archives of resistance, featuring figures like Yasser Arafat and the Fédayins, highlighting the struggle against occupation and debunking false political analyses.

Saab previously covered events ranging from Libya, the October War of 1973 and the Iraq War of 1974. Her engaged work led her to report on civil society, as well as political and social issues as seen in the films screened that evening.

“In '74, she made the first film ‘Palestinian Women’ which was supposed to be shown on Antennes 2 television in France, but the film was censored, so never shown,” voiced Polledri. “This film was immediately deposited in the film archives in France; so it was recovered quite recently and restored by the work of the association.”

Polledri said that no one knows the reasons that led to the censorship of this film. She added that in an interview, Saab said that it was probably the committed role of these women who were active in the Palestinian resistance shown in these films that was viewed as disturbing.

Saab’s coming-of-age journey was broadcasted by powerful images of Palestinian victims in refugee camps of the Civil War.

“Despite being from a Christian-Maronite bourgeois family, she immediately engaged with the Lebanese left and the Palestinian cause,” stated Polledri. “In an interview, she expressed that staying in West Beirut during the siege was the most beautiful moment of her life. She appreciated the strong commitment, community, and close relationships among the people who, despite the siege and bombings, chose to continue living in the city. The film vividly captures the efforts to identify the traces of life and gestures of the Lebanese who remained determined to inhabit the city.”

ElKhairy emphasized the power of image and the enduring relevance of the films due to political parallels that persist to this day. He stressed the significance of addressing censorship not only of these films but also of Palestinian perspectives and voices, particularly those associated with Palestinian resistance. ElKhairy notes that there is a predetermined image of what is deemed "acceptably Palestinian," and these films challenge that perception.

“The films are overwhelming in their portrayal of enduring messaging and language used for over 75 years, including the bombardment of Lebanon and the Palestinian people,” said ElKhairy. “The resistance and its consistent messaging, still relevant today, are crucial to highlight, especially in connection to the ongoing genocide in our current moment.”

Razan AlSalah, Palestinian artist and teacher in the communication studies department at Concordia University noted the juxtaposition within Saab's work, such as depicting a freedom fighter belly dancing and later being trained as a Fidai on the front line, creating a space between images that challenge conventional norms.

This, according to Alsalah, contributes to Saab's ability to showcase images of care amid horror, achieving a utopian quality in her formal approach. Alsalah also added historical context, mentioning Lebanon's link to Palestine during a period when the Christian right wing in Lebanon sought to mirror Israel's ethnostate.

“We can imagine that European connection and how that's kind of a European project as well. And they think of themselves as more European than Arabs,” said Alsalah. “And so this was kind of a mirror of Israel and West Beirut was the opposite of that, like the space where that utopia that she was talking about the kind of flourished and I just wanted to reflect on Saab’s formal approach and how that was reflected in her ability to show us militancy and feminist when I don't know if that I've ever seen that in any other films”.

Annette Diallo, an attendee of the screening, believes that the censorship incident with Cinéma Du Parc reflects Western handling of freedom of expression. She questions true freedom when expressing dissenting opinions, citing concerns about mainstream media ethics and referencing examples like caricatures mocking Muslim prophets in France and the ban on Palestine protests.

“When artists were making those caricatures that were mockingly offensive to Muslim people, they would throw in people’s faces ‘freedom of speech,’” said Diallo. “I find censorship completely absurd and it furthers our distrust of the media, they don't tell the full story, they choose one side, we don't get the full picture. And these are archives, videos of what happened in previous years. You would hope that people would get a chance to see it. “Archives are the most reliable piece of information that people could use to get educated on the subject because the media won't talk about it.”

“We're a cultural organization, we try to do what we can, but ultimately, there's a lot of political work that needs to be done. Canada is complicit [in] that all of your tax money is going to pay for these genocides,” added ElKhairy. “There's so much that needs to be done and there are a lot of brilliant organizations that are doing the work, everything from the postcards that we have—that you can send to your representatives or send to the Prime Minister, or, you know, the protests, the marches—donations are great and the cultural work that we're trying to do.”

To keep track of their further community engagement, the coalition can be reached on Instagram or on their website.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 9, published January 30, 2024.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)