A farmer’s odyssey: How I spent my summer living on organic farms in Greece

The lessons I learned travelling in Greece with little money and a whole lot of farming

After graduating from Liberal Arts at Concordia in the spring, tired of spending my days sitting at a desk, I decided it was time to experience life hands-on. I packed a big suitcase which I later regretted, ditched, and replaced with a small one and left Montreal for a three-month trip to Greece; the motherland.

As a third-generation Greek with roots spread in various regions, including the Peloponnese, Pontus and the Cyclades, I was lucky to have visited many places in the country before. However, this time, instead of being the typical tourist, I wanted to live amongst locals by volunteering at farms.

Having roots on my father’s side in Paros, a small island in the Aegean sea, separating Greece from western Turkey, I made this my first stop. I found an opportunity at a family-run farm named Petra (rock) for the stony Cycladic landscape- overlooking Kolymbithres beach. I discovered Petra by browsing the website of a well-known organization called World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF). I paid a small sum of approximately 40 euros ($58 CAD) to access over one hundred farms in Greece, specializing in various farming practices, such as olive oil production or sheep farms. In exchange for about 25 hours of work a week, I would receive accommodations and delicious food to feed me all week (including my days off) with ingredients from the farm—my favourite Greek dishes such as yemista—and generous outings to local tavernas. Petra Farm seemed to have it all: a good balance between animal life, such as chickens and goats, and an array of vegetables and herbs.

On my first day working on this idyllic property, I was given a plastic basin and directed to the caper bushes. With two other volunteers from Ireland, I spent most of my time harvesting this fragile bush, intricately clasping the small caper between my index and middle finger in a backward gesture. I was searching for both texture and size with every singular caper. Once I had found the perfect one, I tossed it into the bin, making a sound that became funnily mundane, like the sound of a corn kernel popping in the microwave. Before that moment, I had never considered how much precision and time was behind the capers on my Montreal bagel.

By the end of my three-week journey, I had become a pro at caper picking, filling my basin ten times faster than on my first day. Most importantly, however, this experience made me realize the labour behind the food we eat, a process I will now never take for granted.

My time at Petra passed quickly, with salty soaks in the sea and an active social community of volunteers and family. Petra was home to the loveliest people, with the vision of ensuring the continuity of Greek delicacies such as dried oregano, mountain tea and fresh fig jam.

My next stop was the mystical mountain of Pelion. I arrived with the intention to work at a farm that fed yoga retreat visitors, where I planned to spend the next six weeks. The garden was colourful and promising, but the hosts were not committed to taking care of their volunteers, a reality, though infrequent, to consider when WWOOFing. Although disappointed and discouraged at the prospect of having a limited number of farms that would accept me with such short notice, I swiftly realized I had dodged a bullet.

It was bittersweet leaving the beauty of Pelion only after a few days, but I had a feeling something better was waiting for me.

After departing the farm, I found a nearby hotel to rest and consider my next plans. I luckily had relatives in Nafpaktos, a four-hour bus ride away, and I took this opportunity to meet them while buying myself extra time. This transition made me regret my heavy suitcase, which encumbered all my movements, especially in the 40-degree weather. I decided to slowly leave behind my possessions, like a monk in the desert. My cousins took some of my clothes, and I bought smaller luggage. Being with family destabilized the vision of my trip, but it taught me to be adaptable because, in life, things don’t always go exactly as expected. However, every experience, whether positive or negative, offers the gift of growth. While in Nafpaktos, I had plenty of time to consult the WWOOF website and organize my final adventure.

That is when I connected with a woman called Géraldine, who lives on the island of Tzia with her husband George, a third-generation beekeeper in Spathi. Together, they own a picturesque BnB and farm called La Maison Vert Amande. She happened to have free space, and I hastily accepted the opportunity. I arrived at the farm in pitch dark, except for a lantern dimly illuminating the faces of the people I would be spending the following four weeks with. I was warmly welcomed at the table by the hosts and a few guests from Athens. When I sat down, Géraldine placed a big piece of moussaka on my plate, even after telling her I had already eaten. At that moment, with that gesture, I knew I had found a good place.

I spent the next month taking care of various farm animals. Early in the morning and evening, I would feed the chickens, turkeys, rabbits, a majestic donkey named Calliope and two Australian emus allegedly present for “decor.” Most importantly, given the extreme heat present in the summer months, I always kept an eye on their water. The animals naturally became my friends, and I often found myself visiting them during my breaks. Being around them gave me an unexpected purpose, as I knew their life depended on my care. Whenever I approached their coop, they would run to the gate with excitement, a comical sight, especially the wobble of the long-legged turkeys. However, not all the birds were as friendly as their comrades. An emu named Flac—part of a trio-Flic, Flac, Floc—truly gave me a hard time. Our relationship was complex, beginning on a note of fear on my end, which triggered a hostile response from Flac. Whenever I entered her space, with much hesitation, she would run after me in a successful effort to scare me. It took a lot of courage to overcome my fear, but when I eventually learned to stand my ground, she seldom would challenge me. I had never realized asserting your space with animals is curiously similar to standing your ground with humans, an encounter that gave me more self-confidence.

My time in Tzia also made me witness first-hand the effects of climate change on farmers. The island had not seen rain since February, and the land had become extremely dry and desert-like. Strangely, my hosts recounted an ancient myth about how a monstrous lion came to Tzia and drove away the nymphs who tended the spring, bringing a damaging drought. I wonder if the ancients knew how dry the island would one day become.

The water I would use to shower had gone salty, as the water source was drawing from the sea. Géraldine and George were concerned about the increasing heat and dryness, thinking about what their future on the island will look like, with estimates that the climate would “parallel that of Sudan in just a few years,” they feared. I noticed the seasonal harvests, such as tomatoes and grapes, were imperilled. Fruits contain 80 per cent water, but with the earth being desiccated, the harvest was spoiled. The bees, who primarily feed off the island’s thyme flowers, were especially affected. George was worried they would not have enough honey this year to sell to their clients on the island, a considerable source of income to sustain the farm.

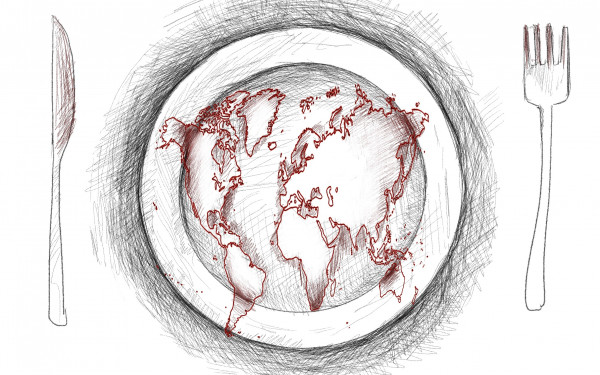

Drought is a serious concern for the island's future and alerted me to the necessity of living simpler lives in which we do not spoil the environment because of individual greediness.

I left Tzia with a clearer image of what was important to me, and living a simpler, more conscious life was just one part of it. I realized how much better I felt mentally, physically and psychologically when I was living in harmony with nature.

I slept in a caravan surrounded by olive trees, and my feet were usually sandy. Life was peaceful, and my habit of ruminating subsided.

Something that marked me forever was when Géraldine expressed that she would “miss the tomatoes once they were done.” I asked her what she meant by this, given that tomatoes were easy to find in Greece. She responded that she only eats what the garden offers, and thus, she would not eat tomatoes again until the following summer, allowing her to appreciate them so much more. Her sharing surprised me, as buying out-of-season fruits and vegetables is common practice back home. But what if we also tried to eat as seasonally as possible? These minor inconveniences are exactly how our ancestors lived before us. If they can do it and thrive, so can we.

For anyone who has ever considered WWOOFing or connecting with your ancestral roots, I believe such experiences are irreplaceable. With a little courage and small luggage, I hope you can discover parts of yourself you did not know existed.

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)