Sex Ed(itorial): The Complicated History of the IUD

This Little Contraceptive Has a Big Story

Today, the intrauterine device is an innocuous device made of either copper or plastic.

However it has a salacious history, one that is rooted in the differences between the global North and South.

While the IUD is a form of birth control intended to fit into a uterus, it has been used to further the political agendas of many people who do not personally possess a uterus, but believe they know what is best for uteri everywhere.

The IUD itself is an innocent piece of technology but has been used for nefarious, racist, and neo-colonialist purposes. In the western world, during the sexual revolution it was painted as the super empowered feminist alternative to the birth control pill until a version called the Dalkon Shield ended up causing great physical harm to its users.

These teeny T-shaped devices are inserted by a doctor through the cervix into the uterus and it remains there. It’s one of the most effective forms of birth control ever invented.

There are two types: Hormonal or non-hormonal. Each functions differently but both ultimately create an inhospitable environment for sperm to exist in. This prevents pregnancy but not STIs.

According to public health expert Dr. Anne Burke, both types of IUDs are, “very effective in preventing pregnancy,” and that choosing between the two comes down to the individual’s preference. Burke is on the medical advisory committee of a campaign to prevent unintended pregnancies, Power to Decide. Their website, Bedsider.org, aims to provide women with information about various birth control options that are available.

The non-hormonal IUD is made of plastic and wrapped in copper wiring. Once it interacts with the uterus’ chemistry, it makes it impossible for the sperm to effectively fertilize the egg.

Some of its side effects are a heavier period and heightened cramps. It’s also cheaper than its hormonal cousin which can be an added bonus for those hoping to avoid introducing synthetic hormones into their body. The copper IUD can be inserted for up to 10 years, according to Burke.

The hormonal IUD releases the synthetic hormone progestin which prevents sperm from reaching the egg by thickening the cervical mucus. Its side effects can include stopping or decreasing menstruation, and can be inserted for a period of three to five years, said Burke.

One of the IUD’s potential negative side effects is expulsion, which means an ejection from its intended place within the cervix. The first year after insertion, 2 to 10 per cent of women will experience their IUDs expelling.

This is, of course, dangerous and can be painful. There is also a risk of pregnancy if the person doesn’t notice their IUD has expelled, as sometimes the expulsion is only partial, but still leads to the same loss of protection.

Some people are more likely to expel their IUDs than others: people under 20 years old, who’ve never been pregnant, have a history of heavy or painful periods, or who’ve had the IUD inserted right after pregnancy are at a higher risk.

An estimated 5 per cent of Canadian women use IUDs. Globally, 14.3 per cent of reproductive-aged women use them.

The pill is the most common contraceptive in Canada, though it is 90 per cent effective, while the IUD is 99 per cent effective. However, the pill needs to be taken at the exact same time every day in order to be most effective, which is difficult for some people.

Once inserted, there isn’t much to worry about with an IUD. There are thin strings that will dangle out of your cervix that you likely won’t feel, but they make removal easy for a doctor when the time comes. At-home IUD removal is never a good idea.

In an email, Burke explained that some possible reasons for the IUD’s relative unpopularity in North America are that some healthcare providers do not regularly offer it as an option to their patients, or that they’re not even familiar with the device at all.

The first documented instance of an IUD being developed was in Germany in 1909 by Dr. Richard Richter, who inserted a ring made of silkworm gut into the uterus.

The next important development to the modern IUD was in the 1920s with the Graefenburg Ring.

Developed by Ernest Graefenberg in Berlin, this IUD differed from its predecessor by replacing the silkworm gut with a spiral of copper, nickel, and zinc.”

It was used widely in England and all British colonies (including Canada and Australia) but not in continental Europe or the United States.

IUDs in their current plastic form have been sold in US markets since the 1960s.

According to Chikako Takeshita, Women’s Studies professor at the University of California and author of The Global Biopolitics of the IUD, they gained popularity as a method of birth control after health concerns emerged around the pill during the 1960s.

The flexibility of plastic emboldened researchers to test out various shapes and forms in the hopes of finding the perfect IUD—one that would prevent pregnancy, expulsion, pain, and excessive bleeding.

The IUD has been the subject of much debate and misinformation, some of it stemming from events in the 1970s involving one particular version of the IUD: The Dalkon Shield.

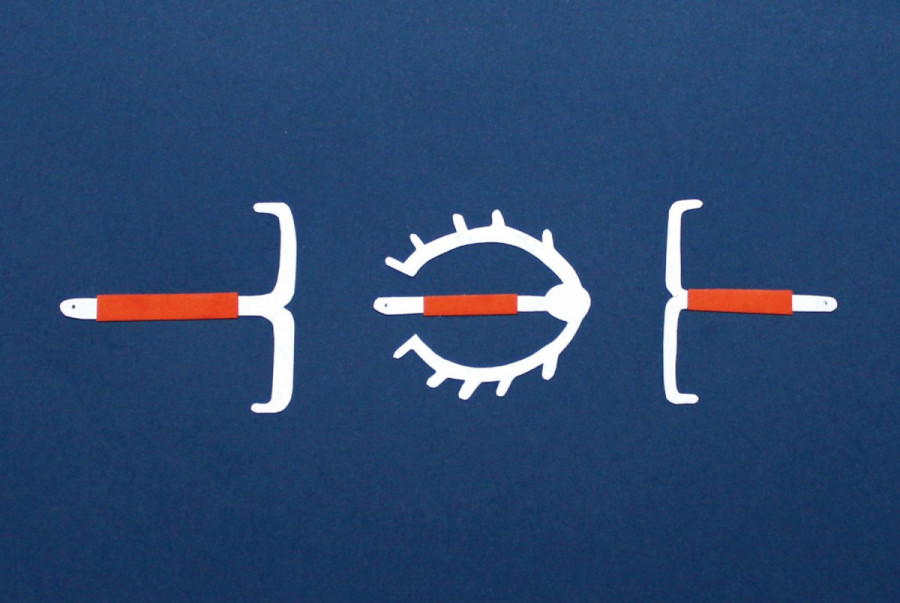

The Dalkon Shield was developed by Dr. Hugh Davis and Irwin Lerner in 1968. It was a little plastic device that looked like a bug, with serrated edges on each side of a rounded body.

It was poorly designed and proved difficult to insert, leading to pregnancy, pain, and an increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease.

Up to 15 women died after miscarriages because they continued to wear their Dalkon Shields; their doctors did not know the devices should have been removed during pregnancy. It left other women permanently infertile.

By 1974, its manufacturer A.H. Robins Co. was hit with multiple lawsuits and voluntarily stopped producing it. By 1986, IUDs were rarely found in the US. But around the early 90s the hormonal IUD Mirena had begun to grow in popularity in Europe, where it was created. The Mirena has since grown in popularity throughout North America.

The danger of the Dalkon Shield was not a misconception, but it led to a cultural distrust of the IUD. Perhaps accounting for its low rate of use in North America in comparison to the 23 per cent of French, 27 per cent of Norwegian, and 41 per cent of Chinese women who use IUDs as birth control.

“I think [the IUD] becomes empowering for women to have, when all kinds of options are available for women and couples including men’s contraceptives, and access to abortion.” Chikako Takeshita

Politics of Birth Control

Takeshita’s book explores the IUD’s differing uses and the opinions surrounding it in the global South and North. She advances the theory that the IUD was used as a tool of population control in the perceived unruly, overly fertile South in the 1960s, and presented as a tool of empowerment for liberated western women constructed as individuals.

Her research outlines the dichotomy of the IUD: Presented and used as a tool of women’s empowerment (but only for the right women, the acceptable ones) while also being used as an oppressive agent of the state and of racist, neo-colonial impulses.

The IUD’s varying uses, both political and practical, can be compared to how a single source of light diffracts into many through a prism, explained Takeshita.

“They’re not separate chapters. I wanted to argue that it was history that is entangled with each other and hides behind this one product or device,” she said.

The metaphor represents how IUDs were used to further varying political agendas, how it has varying uses, and how women at varying intersections of class, race, North/South polarities, and marital status are either empowered or disempowered by their use of the device.

The IUD on its own is simply a physical form of birth control, but according to Takeshita it has been employed as a tool of colonial science.

“Science and tech were used to legitimize the superiority of the colonizing party over the colonized,” she added.

She describes colonial science by explaining how modern science was developed alongside the European colonial fever in the 18th and 19th centuries, benefitting from studying exotic flora and fauna as well as conducting experiments on the colonized people.

“Occupation went hand in hand with the development of science, and science justified colonization by giving medical treatments to the colonized people,” she said.

“The argument that I made was that the development of the IUD was an extension of colonial science.”

“Though it’s no longer officially colonial times, we are still talking about […] the people living in the colonies,” Takeshita continued. “Using scientific methods to control previous colonial land and populations mirrors what colonial science was doing.”

Takeshita notes that before Roe v. Wade assured access to abortion for American women, anything they could do to prevent pregnancy was important to them. This partly explains the construction of the IUD as liberating.

“[The IUD] was received as an empowering tool, but in practice it did create problems for individuals who received harm from it,” said Takeshita.

During her research she encountered women who had a variety of experiences, ranging from positive and innocuous to a woman who had the Dalkon Shield cut out of her uterus, leaving her infertile.

She noted that recently the IUD has been in the news cycle because of Donald Trump and his threats towards the Affordable Care Act. Because the IUD can be inserted and left alone for a relatively long period of time, there was a rush of women hoping to get one inserted.

According to Takeshita, every country has a unique history when it comes to the IUD—especially when it comes to underdeveloped nations where politics lead to NGOs pushing certain kinds of birth control over others. For example, China developed its own IUDs as a form of population control.

Ultimately, Takeshita does not believe in making blanket statements when it comes to the IUD and its uses.Not all underdeveloped countries employ it as population control, and it is not empowering to all North American women.

“I think [the IUD] becomes empowering for women to have, when all kinds of options are available for women and couples including men’s contraceptives, and access to abortion.”

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)