The reality of learning French in six months

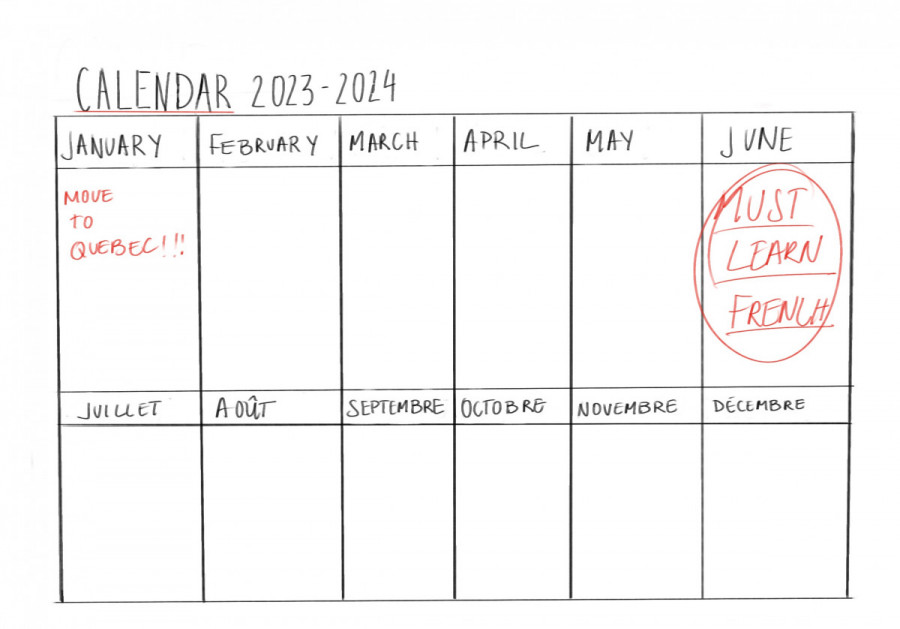

In the aftermath of Bill 96, how are people coping to meet Quebec’s tight deadline?

As a pastry cook in the Mile-End, French is part of Louisa Sollohub’s daily life. Her neighbours and coworkers are francophone, and her vocabulary including “derrière” and “chaud” has helped her get by at the restaurant.

However, working in kitchens is not Sollohub’s end goal.

Back-of-house jobs are coveted by Montreal anglophones and allophones who can’t find other work, and Sollohub is among them. She feels her current intermediate level of French is not enough to pursue her ambitions in the film industry or marketing, let alone to obtain permanent residency.

Sollohub lives in Montreal as an American on a post-graduation work permit with hopes to immigrate to Canada.

To improve her French, she took publicly funded French classes through Francisation Québec last winter.

For four months she juggled two day jobs while taking French night school, but was overwhelmed by the amount of work it became.

To support non-francophones, the Quebec government offers free French language classes through the Ministère de francisation et de l’immigration (MIFI). These French classes are full-time, running Monday through Friday for 25 to 30 hours over a ten-week session. Students can receive up to $230 per week for taking the classes under the condition that they maintain perfect attendance.

“I got burned out after maybe two sessions [of French classes],” said Sollohub. She asked the school to take a break from the classes with the intention of returning after around a month, and they promised to save her spot. However, when she tried to return to the class less than one month later, Sollohub discovered it was not possible.

Quebec implemented Bill 96 in June 2022, placing strict measures on the use of English as well as implementing changes to their public French education program. Enrollment at the public French schools is now controlled by the provincial government through a centralized online portal, Francisation Québec, and out of the hands of the individual schools. In the past, admissions were managed by each French language school.

With the new enrollment process, Sollohub had lost her spot in the class and was put on a centralized waitlist. She was told by the MIFI that the average wait time to get a spot in the classes was three months. Being put on the waitlist eats halfway through the six-month grace period immigrants now have to access government services in English.

The pressure for immigrants to learn French in Quebec long predates the bill, but since Bill 96 was introduced 18 months ago, new arrivals to the province now have a deadline. After six months of living in Quebec, they cannot receive any government services—including healthcare, educational services, and housing and tax ministries— in English. At a hospital, for example, doctors and nurses are meant to refuse to speak English to their patient, unless the patient provides proof that they have lived in Quebec for under six months.

For many non-French speaking immigrants, Quebec’s imposed six-month timeline to learn French is not realistic.

According to a 2018 Cambridge study, it takes about 500 hours of guided learning to achieve basic fluency in a language, equivalent to four or five months of full-time Francisation Quebec classes. However, for many immigrants, especially those supporting families, the $230 weekly income is not enough. Sollohub, and others working multiple jobs, say the full-time class schedule is not feasible alongside full-time work.

Maya Tanatwi, an international civil engineering student at Concordia from Qatar, was also told by the MIFI that she would have to wait three months to take French classes. Upon receiving the news, Tanatwi was somewhat relieved. She said she feels overwhelmed taking full-time French classes alongside her full-time Engineering studies. “I’m pushing it, but I think it’s hopefully doable.”

It does not seem like the waitlists will shorten anytime soon. Gabriel Bélanger, the media relations director at the MIFI, confirmed in an email that “there have been no changes to the funding arrangements for French-language learning services for school service centers and school boards in 2023-2024.” He wrote that 41,438 people took Francisation Québec courses from April 1 to Sept. 30 in 2023. Bélanger did not comment on the length of the waitlist.

Stewart, who did not wish to provide his last name for privacy reasons, is the academic coordinator with the Excellence through Quality Improvement Project (E-QIP), a private language school in downtown Montreal. He said he has noticed the stress of his students rise over the last 18 months.

“Some of the [immigrant students] are with families. Some of them have made quite large sacrifices to come,” he said. “It takes a lot of time and energy to move to another country and take up a position. And then they’re kind of threatened with the prospect of not being able to stay.”

Stewart said that in the past, what drove his students to take French classes was self-motivation. Now he believes, “it’s more of a push, not a pull.”

The high workload and new immigration rules are not the only stressors of learning French amid Bill 96. The bill has also come with a set of bureaucratic barriers.

For Sollohub, the enrollment process for the classes has been “unnecessarily difficult.” She noted that the website has been hard to navigate because ”it’s all in French,” and she still doesn't know French well enough to understand “specific government details.”

Tantawi has struggled with this same issue. “Every type of communication you want to have with the [MIFI], it’s all in French,” she said. “So if you don’t understand French, it’s almost impossible for you to know what they’re saying.”

Sollohub additionally faced issues with submitting her paperwork required to enrol. She received a confirmation email when she signed up for the classes online but didn’t hear back for several months.

According to Solluhub, the process to enrol is “supposed to take a long time, so I thought it was normal.” At the three-month mark she called the MIFI. She was told her documents weren’t accepted because they were submitted virtually rather than through the mail. “It was very not clear that you’re supposed to do it through the mail because they had an option to submit it virtually,” Sollohub said.

Sollohub now has to wait another three months to take the classes.

Bélanger from the MIFI wrote in an email that the new Francisation Québec system “makes it possible to consolidate requests in a single location,” which in turn will “enable better course planning.”

If someone can’t get into the public French courses, it is likely they will have to turn to private lessons, which might not be a feasible option for everybody. The private group classes at the language school E-QIP cost $60 to $75 per person for one 45-minute lesson. For Tantawi, the zero dollar price tag for the Francisation Québec course made it the clear option. She believes, to achieve fluency by taking the private lessons, one ends up paying half of their income. “I wasn’t willing to pay that,” Tantawi said.

The types of students E-QIP attracts has changed, according to Stewart. Since Bill 96, E-QIP has drawn in many business executives and professionals from private companies. Stewart said the students “need to meet the French requirements [to immigrate] and the resources available to them for free are not enough. It won’t get them over the hump in the amount of time they need [to pass the French test for permanent residency].”

Stewart said they receive many students at E-QIP who are dissatisfied with the public system. He said it is challenging to learn a language with more than eight people in a room, “because you’re just not getting the attention you need.”

With regard to the new language laws, Tantawi said she will leave Quebec if “that’s how they feel about us.”

“If I’m going to get paid almost the same thing in other places, why would I stay here?”

Despite the barriers with the French language, Tantawi has appreciated the quality of education she has received at Concordia. “We get very good education,” and “we are treated fairly in Canada education-wise.”

For Sollohub, Montreal is home.

“I have so much motivation to take classes and learn French,” said Sollohub. “I want to have a job where I’m speaking French and be part of [Montreal’s] culture.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 9, published January 30, 2024.