What is Fascism, Anyway?

We Spoke to Scholars to Define the Contentious Term

Words, and their meanings, are important.

Language is the principle way that we interact with each other. It’s our main form of symbolic communication and the tool that we use to understand the world around us. So for social movements, language holds a particular importance—building a common understanding of words and the things they represent is foundational.

For the anti-fascist movement, defining terms can be tricky. This difficulty stems specifically from the word “fascism” itself. The dictionary definition focuses on fascism as a form of authoritarian right-wing government, but fails to describe what fascism is before it actually takes power.

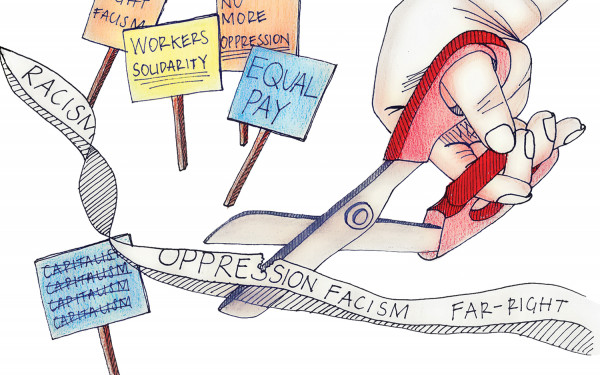

“It’s notoriously difficult to define fascism,” explained Mark Bray, author of Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, in an interview with The Link. The first wave of fascists in the 1920s and 30s, he said, “adopted and discarded ideas at will.” They stole symbols and language from the left-wing workers’ movement, but redirected it towards wildly different goals.

The confusion in defining fascism, Bray said is “especially true in the postwar period, where fascists and far-right groups have adopted from Maoist and Trotskyist and anarchist ideas in a bizarre confluence of perspectives.”

For Alexander Reid Ross, author of the sweeping history of post-World War II fascism Against the Fascist Creep, this difficulty in forming a definition is built into fascism itself. In an interview, he described fascism as “syncretic,” taking elements from both the political left and right, but always striving towards greater levels of social hierarchy and domination.

That, for Reid Ross, is one of the foundational aspects of what makes fascism a distinct political tendency. The cornerstone of fascism is a drive towards greater distinctions between groups—class, race, gender or otherwise. These hierarchies are viewed as “natural and organic,” based on an “irrational understanding of might makes right,” he said.

“Fascism emerged as a rejection of the rationalism of the Enlightenment,” Bray explained. “It was really founded on an emotional appeal towards power and domination.”

“Fascism emerged as a rejection of the rationalism of the Enlightenment. It was really founded on an emotional appeal towards power and domination.”

—Mark Bray

The ultimate goals for fascists, Reid Ross explained, is a “confederation of ethno-states,” where each so-called racial group would have a their own state. Another way to describe this, Reid Ross pointed out, is “apartheid states where cultural minorities do not exist.”

By framing their goals as racial separation, fascists turn the language of diversity upside down. Using this logic, the desired apartheid states are framed as being anti-racist—because they guard against the supposedly homogenizing force of multiculturalism, which is framed as the real racism. This is the logic behind the white supremacist slogan that “diversity is white genocide.” Using this trick of language, the fascist movement hides its own intentions of genocide and ethnic cleansing.

The entirety of the far-right cannot be accurately called fascist, though. In his book, Reid Ross differentiated between fascists and a broader category which he referred to as the radical right. The two groups share many of the same views, but the radical right tends to be more open to working within democratic parliamentary systems.

Reid Ross was quick to point out that, in practice, the lines separating fascists and the radical right are very blurred. “The divisions are there, but they’re frequently flouted by the participants,” he said. “You have people serving as conduits or bridges between movements.”

Milo Yiannopoulos, for example, “described himself as a classical liberal but actively and with intent worked to bring messaging from white nationalists to mainstream conservatives,” Reid Ross continued. “The issue with the radical right in general is that this is often their function.”

Explicitly fascist organizations may be small, but they pose an outsized threat beyond what their numbers alone would reveal. Unnoticed fascism tends to fester and become dangerous in three main ways, Bray explained.

“The most obvious is that they’re violent and murderous,” he said, referencing the growing number of murders and terror tied to far right groups in the United States. That same danger presented itself in Quebec City on January 29, 2017, when a racist murdered six people in a mosque. The alleged shooter had previously described how he only wanted white immigration in Quebec, a mirror of common white nationalist talking points.

“Secondly,” Bray explained, “they influence public discourses around issues like immigration, affirmative action, questions of race and national identity, to a degree that’s beyond the proportion of their numbers.” Here in Quebec, the past year has seen mainstream political parties pandering to far-right sensibilities by passing legislation such as Bill 62, which would restrict niqab-wearing Muslim women from accessing public services.

Lastly, Bray says, “Mussolini started out with 100 people, and Hitler started out with 54. You never know where a small white supremacist or fascist group can go. So when anti-fascists argue for stopping them before they take the first step forward, that’s an argument about the potential for these groups to grow.”

“It’s unlikely, but it’s possible, and I think that needs to be taken into account as well.”