My Big Fat Catholic Family

What I Learned About Family Size and Catholicism in Quebec

Grampy—my grandfather—used to hate dogs beyond all human understanding, my mother and grandmother would tell me.

He’s a fascinating man. I know everyone says this about their grandparents, but we are all entitled to our own family intrigues.

Being curious, I dug for the reason behind his canine contempt, and this became a Pandora’s box of questions I would carry with me throughout my childhood and to this very moment.

Grampy had 15 siblings, and the portrait of his family haunted me for the sheer size of it.

I was able to narrow down a few things. Culture and location play a large role in why they had a big family—but I missed the influence of Catholicism on the size and traditions of Quebec families.

It was said that no one knew when Grampy’s mom, Grand-Maman Tardif, was pregnant; babies would just appear in the house, and an older sibling would volunteer to look after it to give Grand-Maman the ability to continue being the homemaker.

She was always revered by Grampy, who was endlessly fascinated by her ability to cook for 18 people, multiple meals daily, in good times and bad. Her inexpensive soup recipe is a family fixture to this day.

She sewed clothes, hosted visitors, kept her philandering husband in check, and birthed and nurtured an endless stream of babies—16 of which survived.

Like many elders, he recounts a trek to school that resembles the plot of an entire film, a journey lasting multiple kilometres that begins at the family farm.

Many Quebecers in rural areas, Grampy’s family included, raised pigs and other farm animals and did a variety of odd jobs around the farm to help their parents. It goes without saying, however, that reeking of agriculture might prove traumatic to many kids attending school with non-farming peers.

Another issue was the siblings having so few pairs of shoes between them, sharing one or two pairs to wear to school. The day his mother’s dog ate one of their only pairs was the day his hate for dogs was carved in stone, relatives explained. Mom said pets in general were nonexistent in his house, despite his later successes as a contractor and as many shoes as he wanted.

While the woman is clearly as close as it gets to a saint in my eyes, why on earth would anyone have that many children?

“The curé would come by and ask indirectly why we weren’t having a baby that year.” —_Grampy_

Some of her children went on to have as many as 10 of their own, and the family is so big I don’t even know everyone in it. I’m acquainted with three or four distant cousins at most, about four of Grampy’s siblings, and a handful of other relatives I ran into on some occasions as a child.

I assumed it might have been the region, lack of birth control, lack of sex education, or pure need for farm labour that made for such big families.

Grampy would discuss the church at times, but always with a tinge of bitterness. He later became an evangelical Christian, but it never gave him much sympathy or feelings of common ground with Catholicism.

“The curé would come by and ask indirectly why we weren’t having a baby that year,” he would say bitterly of the priests that would visit them. God forbid Grand-Maman take a break from birthing.

The above was corroborated by other relatives, who all seem to have great reverence for the matriarch. At a time when women couldn’t even open a bank account without their husband’s signature, and just around the time where women began to have the right to vote, a woman like Grand-Maman commanded respect by meeting and exceeding the standards of her time and place—fertility, cooking, and managing a household.

The thought of this gives me dismay. This was at a time under Premier Maurice Duplessis when the church was at the height of its influence in Quebec.

In another era, she could have been me, studying what delights her, being told the sky’s the limit, facing some barriers due to gender that have, at least, improved somewhat and can feasibly be fought. At my age, 25, she was probably already married and with multiple children. At my age, my own grandmother was married with kids. My mother was married by 23 with two children.

I am, thankfully, unmarried, childless, and allowed to plan for the future and career I dream of. This is thanks to the hard work and sacrifice of so many women before me, and despite the men that would have sat by and allowed the status quo to prevail.

Perhaps our family size waned over generations with the decreasing influence of the church and religion in general; birth control and feminism becoming more mainstream may also have played a large part.

Over time women asserted that they can be more and do more than just have babies. Whether that translated to us just ending up doing more is still up for debate.

Many argue the allocation of domestic duties is still not split equitably between men and women, and women are expected to be mothers, career women, and pin-up girls all at once. The pressure we feel today is monumental, but I’ll argue it’s so much better than managing a household of 16 children and their children. The church under Duplessis dominated radio, schools, and hospitals. Women who were pregnant out of wedlock went to the nuns, who would take the children into orphanages. Many such “illegitimate children” were given or even sold to unsuspecting Jewish families who were unable to conceive. Others languished in miserable underfunded orphanages and were indoctrinated.

This does not even begin to describe the horrors Indigenous people suffered at the hands of the Catholic Church.

One could argue that censorship, the use of religion for control, and rigourous traditional standards imposed on women, especially on birth, sounds like fascism. I wouldn’t disagree.

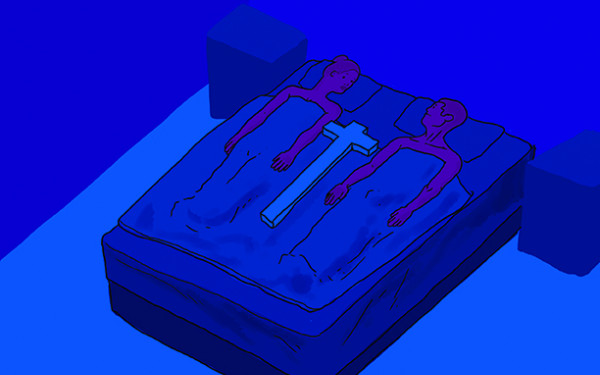

In what many argue is a post-Catholic society, we still see churches and crosses everywhere, remnants of a brutal past that kept the everyman under control and the everywoman his property.

When I see Quebecers today insisting a woman remove pieces of clothing intended to cover her for her own liberation, the irony is not lost on me.

Every day, I am far more offended by Catholic symbols in hospitals in rural Quebec, where they represent the realest oppression Quebecers have fought against, than women choosing to cover their head in a state where they have civil rights and freedom of choice.

Every day, I strive to live a life that makes my Grampy proud and Duplessis turn in his grave.