Tuberculosis: The Airborne Disease Displacing Many Inuit

Limited Health Resources in Nunavut Push Those Fighting TB to Migrate South for Treatment

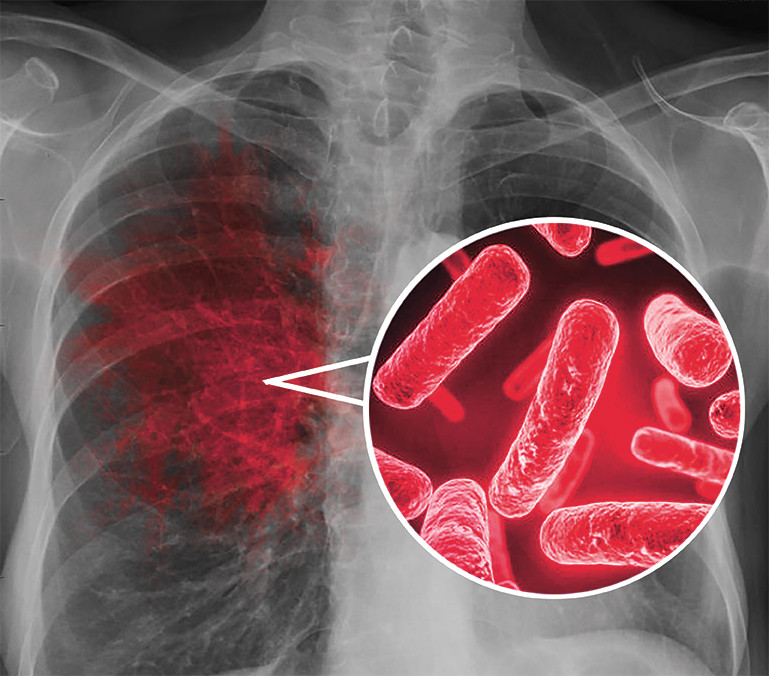

Coughing up blood, aching all over, chills and fatigue, all while fighting a fever—these are the symptoms of the airborne disease tuberculosis.

Now imagine fighting these symptoms while resting in a poorly insulated and overcrowded house, shared with other people, some of whom are also fighting TB. If you want treatment, the best option is trekking hundreds of kilometres south, leaving behind your community for an unforeseeable amount of time.

This is the reality for many Inuit living in Nunavut. Nunavut is home to one main hospital, located in the capital Iqaluit; the hospital has 35 beds available, and provides aid to approximately 16,000 people in the Qikiqtani (Baffin) Region—home to 12 communities. There are other healthcare centres scattered across Nunavut, however as tuberculosis is affecting such a large number of those within the community, there is not enough adequate services to address such large rates of TB.

Living in a country with a high quality of life, it may seem like a treatable illness. But for Inuit living in this region, the chances of contracting TB is 290 times higher than a Canadian-born non-Indigenous person.

Tuberculosis is an airborne illness which most often infects the lungs. It’s the deadliest infectious disease in the world. In 2017, it infected 10 million new people and killed 1.3 million.

TB is a disease of poverty. This is due largely to the fact that it spreads easily in places which lack basic health services, proper nutrition, and adequate living conditions. Hence why more than 90 per cent of TB cases and deaths occur in developing countries.

TB rates among Canadian Inuit have been on the rise since 1997, and are now at a crisis level. How has a country ranked twelfth in human development allowed a curable and treatable disease to contaminate a community for so long? Well, the answer is not simple, given it requires an understanding of the past, an awareness of the present, and a genuine concern for the future.

A Look Into Tuberculosis’ Past

Like most developed countries, Canada has seen its TB rates diminish over the years due to an improvement in diet, sanitation and overall living conditions. Before the Second World War, there were 14,000 new cases of TB reported each year in Canada. We have experienced a sharp decline in rates since then.

Health Canada has estimated that around 1,600 new cases are reported every year. Compared to other countries, Canada is considered to have a low TB rate. Even though this may be true for most Canadians, there is one group for which this is not.

Indigenous peoples as a whole suffer from TB at a rate 32 times higher than the overall Canadian population, with Inuit disproportionately affected.

Given that the history of TB among Indigenous peoples in Canada is simply inexcusable, the issue has not had great coverage by Canadian media or discussion within our government.

“[In order to] bring about awareness we need to clearly understand history,” explained Vicky Boldo, a cultural and community support worker at Concordia’s Aboriginal Student Resource Centre.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous peoples remained relatively untouched by TB. Even after contact was made, TB rates remained rather low. The history of TB among Indigenous people therefore begins at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, when some Indigenous nations began being infected at epidemic proportions in Canada.

When rates of TB contamination first started growing, deaths were due to low immunity, however it quickly became, and remains, a societal issue.

During this time, the cases of tuberculosis were growing across the country. Sanatoriums were therefore created as a means of dealing with the disease, as these were used as long-term care facilities to address chronic illness, alleviating the stress placed on other healthcare facilities. These institutions offered patients isolation, fresh air, and rest as curative methods. However, for the Indigenous people who were sent there, sanatoriums only further added to their suffering.

Similarly to how the Indian Act allowed the government to place children into residential schools, the act also allowed officials to forcibly admit Indigenous patients to sanatoriums. Those who were emitted to sanatoriums were often relocated far away from their communities. Many would end up spending years at these institutions, and some would never return home.

It wasn’t uncommon for the families of those who died to never be informed of their loved-one’s passing. Furthermore, given the rampant rates of TB in residential schools, these two institutions became interconnected, and their trauma shared. To highlight just how serious the situation was, during the 1930s and the 1940s, the rates of TB among children in residential schools was 8,000 per 100,000 people. The Museum of Health Care states that these are among the highest rates ever reported anywhere in the world.

According to an investigative report done by the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, survivors of the sanatorium era recall undergoing invasive medical experimentation, in some cases being surgeries, and watching deceased patients being buried in unmarked graves. A research paper published in the Critical Public Health journal cited that when people returned from sanatoriums to their communities, they often felt unwelcomed, given that they had been physically and spiritually distanced for so long.

Moreover, many began to believe that sanatoriums where places people were brought to die. However, for those who managed to return, intergenerational trauma arose as a result of TB and the treatment of it.

“The emotions that we carry from violence that we’ve lived, violence that created trauma, can remain as a core symptom,” said Boldo. Boldo, who is from Cree, Coast Salish, and Métis heritage, can only speak for herself, but she says that once she was able to take responsibility of her life and have her voice heard, her healing really progressed.

“We started hearing about TB here and there, but it’s not really talked about, it’s one of those things that’s spoken, but not really spoken of,” said Rev. Annie Ittoshat, who works with the Southern Quebec Inuit Association.

The stigma still associated with this disease is telling, as the current experiences of Indigenous people dealing with TB are interpreted based on the past experiences of others in their communities. What followed was the creation of stigmas and fears regarding TB and seeking treatment for it. Some shared their hellish experiences with their community, but often many chose to agonize in silence. This has led to ongoing intergenerational trauma and mistrust of healthcare practitioners.

It is especially precarious today, as most Inuits infected with the disease must seek treatment down south, and can often not be given a timeframe for the duration of their stay. Ottawa tends to take in the most patients from Nunavut, while other patients head towards Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Montreal. Thus, it is not uncommon for some to refuse treatment, given they fear that if they leave their communities, they may never return.

Not seeking treatment for a disease as contagious as TB is detrimental, as it leads to more people becoming infected. Changes in the ways TB is treated in Nunavut is desperately needed. If things are to remain the same, then the situation for the Inuit will never get better.

“The Inuit People have a massive capacity to deal with this, [we need to] make it possible for them to do the prevention, screening and care for their communities. They are much better placed to do than anyone coming from the South.”

— Rachel Kiddell-Monroe

The Issue At Hand

TB rates amongst Inuit living in Canada have remained astonishingly high. This can be blamed on number of social and economic factors, but the biggest one is not having access to a healthcare program that caters to their needs.

“We need to start listening to those living with certain conditions, they know what’s happening,” said Boldo. “We need to respect the fact that they know how to manage their health. That they [still] may be affected from the violence that created their trauma.”

There is no shortage of research which call for the health care system to begin providing Indigenous teachings and historical context to practitioners working up north. Many also suggest the need to include community members in the treatment programs and increase the amount of Indigenous people working in the healthcare field.

“When we think of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples that wrapped up in 1996, there were over 400 recommendations on what was needed to improve the lifestyles of First Nations in Canada and it always comes down to self-determination and self-governance,” said Boldo. “We know what we need. We are living it frontline.”

In fact, call number 23 of the Calls to Action published by Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada states the need to, “Increase the number of Aboriginal professionals working in the health-care field. Ensure the retention of Aboriginal health-care providers in Aboriginal communities. Provide cultural competency training for all healthcare professionals.”

While the Canadian Government is lacking in its involvement and commitment towards ending TB in Nunavut, there are some independent initiatives who understand what needs to be done and are taking action.

Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, the general director of the Montreal-based See Change Initiative, explains that the initiative’s aim is to alter the way TB treatment in Nunavut is dealt with by adopting a community approach. This means involving the Inuit in their own solution.

The See Change Initiative is working towards empowering communities to deal with TB. “The goal of the initiative is to support a project that is community-based, and community-led,” said Kiddell-Monroe, an experienced lawyer and activist who has worked with grassroots and Indigenous organizations, as well as with Médecins Sans Frontières.

The Initiative wants to change the way healthcare is dealt with in Nunavut. “The Inuit people have a massive capacity to deal with this, [we need to] make it possible for them to take part in the the prevention, screening and care for their communities. They are well placed to do that.”

“Inuit in Nunavut have a long history with TB. It is extremely unfortunate that the rates continue to be so high today and speaks volumes to the question of whether enough is being done,” said Tina DeCouto, the director for social and cultural development for Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated.

NTI is the legal representative of the Inuit of Nunavut in terms of Indigenous treaty rights and negotiations. “However, with the release of the TB Elimination Framework, NTI is working with government to design and implement TB elimination action plans that is customized to reflect Nunavut’s priorities, needs and strengths.”

Part of this action plan, recommended by the World Health Organization, calls for getting community members involved with treating and preventing the disease. “Some of the tasks which nurses are doing, could actually be much better done by members of the community themselves,” said Kiddell-Monroe.

In the case of Nunavut, the participation of community members would be useful for tasks like follow ups, which are done in people’s homes. Unlike a non-Indigenous nurse from the south, a community member can understand the culture and language; thereby offering additional comfort to the patient seeking treatment.

“We situate these doctors and physicians as some sort of elite, upper crust in society,” said Boldo, “[but] the expert in the room at any one given time is the individual who is sharing their story.”

Kiddell-Monroe echoed that complementing the traditional healthcare practitioner with a member of the community may make people feel more comfortable seeking out and receiving treatment. This is much needed in order to care for the intergenerational trauma some still deal with due to past abuse obtained in sanatoriums and residential schools.

Looking At The Future of Tuberculosis in Nunavut

“We broke the wheel by making people dependent on the structures that came from the south,” said Boldo. “We’re not learning from the mistakes and trying to do things differently.”

There is a clear need to revolutionize the traditional ways of approaching healthcare and adapt to one that is appropriate for the needs of the individuals it is supposed to serve.

“It’s changing things to a team-based approach. So instead of the traditional medical hierarchy with a nurse at the top and everything running down, [we] create a team where the nurse works alongside communities giving training and support,” said Kiddell-Monroe.

This is done in the hopes that eventually, “The Inuit people can run this project themselves and won’t need support form the outside,” said Kiddell-Monroe.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada states that, “…the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools.” This means that self-determination and independence from medical services provided by the south is essential for the treatment and prevention of TB in Nunavut.

The emphasis on self-reliance and self-determination for Indigenous peoples is not an invitation for the rest of Canada to ignore the existence and strife of these people. Rather, we have a duty to stay informed and pressure the government to do the same.

“Up north is beautiful, it’s a hidden gem of Canada, but it’s very different at the same time,” said Ittoshat. “There’s that gap that we have that should be broken. One thing that can break this unspoken wall is going to events and finding out what’s going on.”

This article has been updated after a second interview with Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, so new information could added and clarified.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

5_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)