The “I” Word expo unbolts art gallery doors

Curating art to end stigma of immigration across new spectrums of media

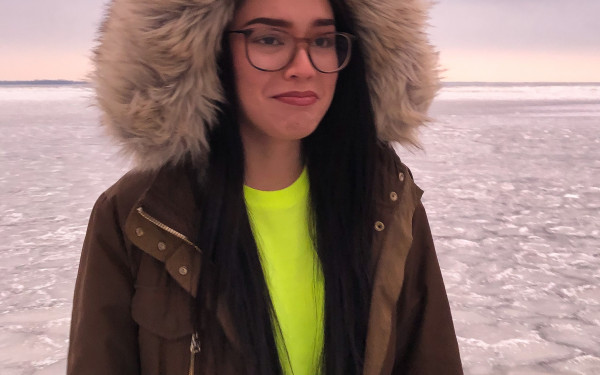

When Joliz Dela Peña saw the artist call-out submitted online by Underdog, a newfound Montreal recruiting agency for local artists, she already had a story to share in mind, one that affected her family. She performed “Kain Na”—which means ‘Let’s Eat’ in Tagalog—to success at WIP, an art gallery located on St. Laurent Blvd.

Curators Haein Oh and Olivier Stainvil posted the call-for-submissions with community-funded organization Boiling Point as well in the selection of artists for the exhibit.

Artists were each given the same task: to define what the word immigration means to them.

People were moved close to tears as Dela Peña performed, her fingers dipping a bowl of rice with pre-filmed family members eating as well through the glow of different laptop screens. She sat in front of a camera wearing a white gown with butterfly sleeves over a bright red t-shirt peeking from the back seam of her dress. The tourist t-shirt exclaimed in bold: “J’aime Montréal” across the front.

And the white dress she wore that evening was a Filipiniana, also known as the María Clara gown, a late-19th Century derived dress worn by women in the Philippines. The name is from Noli Me Tangere, Latin for 'Touch me not,' a 19th century novel by Jose Rizal.

“The first week of quarantine, I had this idea where I asked my sisters, my dad and my mom to film themselves eating and not talking,” she explained. “And I would make an installation of us eating as a family together.”

When Dela Peña was seven years old, her mother flew across the globe to find work as an overseas Filipino worker, a term used in the Philippines to refer to migrant workers, having to leave her children and husband behind.

“The jobs are mostly [for] caregivers. They just have to have a certificate for being a nurse in the Philippines to get here,” she said.

After the departure, Dela Peña’s mother was working while living alone in a small apartment in Canada. “Her dinner here in Canada was our breakfast there,” the artist explained, describing her mother’s subsequent homesickness and loneliness. “Sometimes different time zones are very tricky, so most of the time, she would just eat alone.”

The artist couldn’t see her mother for a whole decade, who was sending money back so the family could be reunited again in Canada for better opportunities.

For Dela Peña, the word immigration means family reunification. “Not just leaving my home country,” she said.

“Is here the promised land that they portray it to be?” questioned the co-curator Olivier. “This is what came to mind when we interviewed the artists.”

“It’s two different realities,” he said. There are close to no jobs available, neither are there many photographers and graphic designers in Haiti, according to Olivier. “You go to school to become an engineer.”

Olivier flew to Canada to study engineering at Concordia. Now, he is a photographer and graphic designer. The “I” Word was the first exhibition that he curated.

“I called my dad. He was at work. I was like, ‘yo dad, I have to talk to you.’” Olivier explained. “I’m going to drop out of school.”

“He was super angry, and was mad at me for a long time,” Olivier continued. “He kind of accepted what I’m doing right now.”

Each work of art within The “I” Word was accompanied by a personal note written by the artist, defining through their own words what it means to them.

Most of the artists chosen were from diverse, underrepresented communities and cultures, first or second generation immigrants with stories of their own. They illuminated the struggles experienced by their parents and grandparents, and how their identities were consequently shaped in Canada as well.

“I asked my sisters, my dad, and my mom to film themselves eating and not talking and I would make an installation of us eating as a family together.” —Joliz Dela Peña

“I have confidence,” said Oh, co-curator of the event, speaking on her skills as an artist. “I’m pretty good at it.”

Oh founded and started Underdog on her own terms after signing up to participate in an art show at her university. They refused her work, but that motivated her to invent and curate her own exhibit.

When she went to her school’s fundraiser to see the exhibited works for herself, she observed that the artist line-up had a clear lack of inclusivity and diversity within the selection process.

She did her first show with Underdog on Feb. 1st. “I didn’t even know curating was an actual job. I didn’t know you had to study for it. I just did a show.”

An underdog is defined as a person or group that is expected to lose in a competition, but Oh took the idiom as an opportunity to showcase the talented works of underrepresented artists within the Montreal community.

“It was in my parents’ restaurant, because they have a sushi restaurant,” said Oh, her first artist call-out being for BIPOC only. “A lot of people showed up and I did not know who they were so that was a good sign.”

With the Black Lives Matter movement gaining momentum, Adia Parris began working on her short film as soon as she stumbled upon the call-out for The “I” Word online. “With all of the violence, I really feel like I have to make something to express what I am feeling about this movement,” she said.

Parris installed her film “Diary of a tired Black woman” before she flew back to Barbados.

In her short film, Parris is wearing a white lace spaghetti strap dress in a series of close ocular shots. “You see me,” she declared.

For Parris, the theme that came to mind for her film was fatigue. “Tired just trying to keep up with everything that’s going on, trying to make sure that I am expressing enough. Am I sharing enough information? Am I reading enough? Am I writing enough?”

“As a Black female, am I representing my race enough in this movement?”

“Diary of a tired Black woman” was also about immigration, “thinking about how Black people came to America, how they were taken from their homes, how they were brought to do work,” she said, “not by their own accord.”

The Barbados-born artist is currently studying Studio Arts at Concordia, experimenting and working with a variety of materials and mediums, from drawing, using paint, photography, video and technology. She hopes to acquire permanent residency in Canada so that she can continue collaborating and participating within the community she built for herself in Montreal.

Mizuki Khoury submitted her art as well, called “Immigration,” which was entirely dedicated to her father. There was also a larger piece titled, “Ketamine Cinnamon Morgue Coffee,” which hones part of her mother’s culture who is half-Japanese.

“I’m not an immigrant, but both of my parents are,” she said. “My dad, he grew up in the civil war of Lebanon. He had a lot of stories about how he grew up, and how he changed.”

“I wanted to honour him and his story through the painting,” she said, adding that she prefers that the visitor uncover the story of her works for themselves rather than having to explain the symbolism behind them.

Beside “Immigration,” the excerpt located next to the piece reads: “The word immigration sounds like the voice of Papa in my head. Just like when he tells me about how he would collect shells of explosives with his friends after a night of bombing.”

Her vivid, expressionist acrylic works incorporate a recurring metaphorical figure painted in all black with wide bubbly eyes.

“That is me,” she said. “It’s a nameless character and very anonymous. It’s how I feel in the world. I feel like I’m kind of hidden.”

“Each piece is me saying a story. Every element is a piece in the puzzle,” she said. “I think the ‘I’ means a lot of extremes, not just cultural, but emotional. I have a clash of a lot of cultures, Montreal and Lebanon and Japan.”

Divya G. Singh presented a colour-pencil portrait of her father, copied from a photograph of him holding her as a baby covered in a light blue blanket. The photo was captured in Gaspésie by her mother when they had just arrived in Canada.

“My father’s from India, and I was born in India,” she said.

In addition to the solitary portrait of her father, Singh also showcased two graphite pieces with separate images of rabbits sparring with one another. “They are so different in style,” she noted.

If Singh could describe what it feels like for her living in Canada as an individual, she would describe it as a feeling of in-betweenness. “Our family is Indian, but culturally, I’m pretty much Canadian.”

“In-betweenness means you’re in the middle, and I find myself in the middle in many ways, in a lot of my experiences, and I guess immigration is part of it,” she said. “Immigration is such a different experience for everyone.”

“I had a lot of experiences of rejection in my life,” she said, and that society tends to only visibilize certain types of identities in Quebec. “I just want the experience as an identity in Quebec to be this plurality.”

Singh attempts to transcribe the feeling of in-betweenness across multiple mediums, “colliding my experiences as a woman of colour who is white-passing, who is bi-racial in Quebec,” she said. “All of these identities, they collide, they intersect and my artwork will eventually be that.”

Léonie Beaulieu’s work consisted of a large cell phone snap code that hung on the wall like a portrait. Visitors who passed by had to scan the code, gaining access to the interactive game she had created, “Bà Ngoại,” which means maternal grandmother in Vietnamese.

“My grandma is a Vietnamese immigrant, and I kind of took her story and made it into a game that you can interact with,” Beaulieu explained. “And then you can talk with her a bit about what she has to say about her experience.”

Packaged in 8-bit graphics, the game is a non-linear depiction of her grandmother’s house. Viewers can unravel the story, scanning and pressing through the rooms, furniture, household items and pieces.

“The game is that you go see her while she’s sick and you take care of her, and you get to hang out in the house,” she said. “You get to talk with her about her story through these objects.”

Beaulieu explained that both of her grandparents on her mother’s side came to Canada during the early 1950s, before the Vietnam war. They were granted scholarships by way of the Colombo Plan, which was established after a meeting of the commonwealth foreign ministers in Sri Lanka—which was still Colombo, Ceylon—in 1950.

They both studied in Canada but when the war broke out, they were unable to fly back to Vietnam. “They had my mom and my aunt, and they kind of made their life here,” Beaulieu continued.

“[The game] talks a little bit about her, first off, her family in Vietnam, her background,” she explained. “Her dad was part of the Independence movement in the 1950 through the 60s.”

“There’s one about her experience of moving here, how it was hard, how she only had one dress,” she continued. “That’s the only dress she wore.”

“There was a whole question of her studies here, and how she wanted to study engineering, but when she sent her application, they didn’t accept her because they figured out she was a woman, and women did not study engineering in 1960s Quebec.”

Completing her Master’s degree in history at Université de Montréal, Beaulieu’s video games mainly focus on themes of memory and various identities less represented in popular media, story-building on topics of immigration and LGBTQ+ experiences.

After Dela Peña’s performance of “Kain Na,” the laptops played ongoing loops from the Filipino media to replace the faces of her family members eating—clips that would air today and in the ‘90s, simultaneously.

The short videos, in unison, showcased scenes from soap operas, talk shows and daily entertainment she used to watch as a child growing up in the Philippines.

“There are a lot of murderers under the government, and it’s not being seen,” she explained. “In the Philippines, we have the Anti-Terror bill where your level of freedom of speech is actually limited.”

There were also news broadcastings of the political— demonstrating the country’s suppression of press coverage.

This article originally appeared in The Food Issue, published November 3, 2020.

_copy_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)