The Evolution of Labour Struggles in Quebec

A Peoples’ History of Canada Column

It’s not an exaggeration to say that a generation of young people was profoundly influenced by the 2012 student strike.

From the militant carré rouge, to the conservatives hissing about the entitlement of young people, all parts of society stood up and took note of the maple spring five years ago.

The rate of university tuition probably isn’t the first thing that comes to mind at the mention of Labour with a capital L. Many attempted to discredit the student strike on that basis, drawing a line between the hardworking, ordinary people of Quebec and the impractical, no-good intéllos cutting class and lighting cop cars on fire.

It’s true that the students on strike didn’t physically jam the means of production—they couldn’t seize every MacBook, destroy every chalkboard. So the connection from factory workers who cut off access to industrial looms and textile supplies to political science students banging pots during “noise disruptions” to cut off access to cultivating intellectual labour at a lecture hall isn’t made intuitively.

But although their strike didn’t block access to any mines or stop any factories from churning out undergarments, the student work stoppage is emblematic of the power the Quebec labour movement has shown for decades. It’s the most recent manifestation of collective power that’s kept worker-capital relations tipped marginally less in favour of the latter since the turn of the century—albeit now in a post-industrial economy.

In 2012, the strikers affirmed their right to respect as intellectual workers. The students realized that the for-profit, state-subsidized universities couldn’t function without them, regardless of the fact that the labour they produced was immaterial.

From the Miners to Marois

Picture a millennial, sleep-deprived philosophy undergrad coming home after a ten-hour shift in the dish pit for just long enough to down a redbull before running to the library to churn out an essay in Western political theory. Drowning in debt, fed up with sky-high administrative fees, and decked out in a red felt square, Montreal has no lack of intellectual labourers pulling a double shift to pay for their education.

The dime-a-dozen dishwashing intellectual labourer is a far cry from the chain-smoking, flat hat-wearing miners of Asbestos in 1949. It might not seem fair to compare spending eight hours hunched over a laptop to wading into the depths of the earth to hack up cancerous insulating material, but there are more similarities to their struggle than you would think.

Let’s start by laying out some basic facts.

The asbestos strike of 1949 involved 5,000 miners from Asbestos and Thetford Mines. It lasted for four months, from February to July 1949.

Their demands were to eliminate the cancerous asbestos dust from their work environment, a 15 cent hourly raise across the board, and union consultation in all cases of promotion, workplace transfer, and hiring. Before the strike began, the main mining employer, Canadian Johns-Manville, countered with a five cent hourly raise and some basic workplace improvements. The bosses refused all other demands by the workers.

As negotiations got under way, the miners union—the Commission des relations ouvrières—lost faith in the arbitration process.

“It was in this climate of exasperation with the company and the government that the miners decided by a vast majority to go on strike without going though the legal arbitration process,” Jacques Rouillard explained in his book on Quebec labour history.

The illegal strike was enough for the government to remove the union’s accredited status. The miner’s employer hired replacement workers to break the strike, took out injunctions against picketing miners, and brought in the provincial police.

Maurice Duplessis—the Premier of Quebec at the time—was pissed. Duplessis wanted to get business back as usual, and demanded that the strikers get back to work and stop breaking the law. When the workers persisted, he accused them of being “saboteurs and troublemakers.”

After four months, the strike wound down. The miners won certain short-term concessions, chiefly the recognition of the union, hiring miners based on seniority, and amnesty for striking workers—though this didn’t stop the company from legally pursuing certain strikers. In a more lasting win, the miners got the company to agree to set up an arbitration tribunal to agree on a collective agreement that would be re-negotiated every two years.

The first of these tribunals won an hourly raise of 10 cents an hour. On the flip side, they failed to force the company to eliminate asbestos dust in the workplace.

Though the cancerous dust persisted at first, over time the collective agreements signed with Canadian Johns-Manville afforded some of the best conditions in the industry.

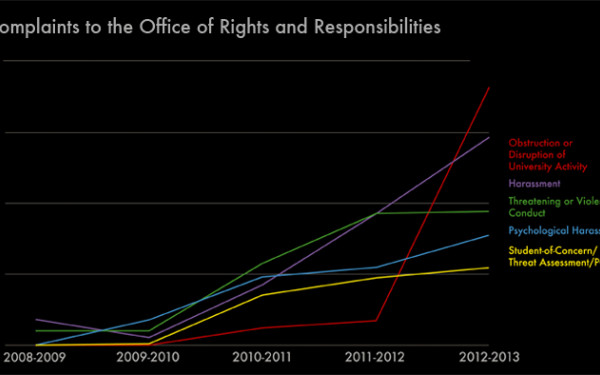

Fast forward about 60 years and compare the numbers.

There were over 150,000 students on strike during the peak of the maple spring. The strike lasted for eight months, from February to September 2012.

The student’s initial demand, faced with a proposed tuition hike of $1,500 over a five-year period, was to freeze provincial tuition. Over time, many student groups would additionally call for completely free education. The Liberal government didn’t concede to their demands at any point.

Quebec is exceptional in giving student groups legal status. There isn’t any specific legislation on when and how student unions can go on strike, but that didn’t stop the Liberal government from doing anything they could to stop them.

Bill 78, or the “act to enable students to receive instruction from the postsecondary institutions they attend,” was passed in May 2012. It made it illegal to form a picket line around a university campus, and restricted protests within universities if they prevented students from going to class. The bill also made it illegal to protest with over 50 people without submitting a route to police in advance.

The nightly demonstrations that happened for months and occasionally engendered collateral property damage led many to dismiss the students as rioters and anarchists.

As the new school year approached, the Parti Quebecois was elected and froze tuition fees, in line with campaign promises.

Now, students in the new millennium don’t have to deal with asbestos dust in their work environment. But that doesn’t make the poverty that many students endure acceptable.

As the Quebec labour movement adapts to the new post-industrial landscape, it’s more important than ever to remember that the insults levied at students and service workers are the same ones used to legitimize the miners, textile workers and other industrial employees.

A pen is just as legitimate a tool of labour as a pickaxe. If it seems impossible for immaterial labour to win workplace recognition, it might be useful to remember that less than 70 years ago, our industrial predecessors were fighting the same battle.