The Dangers of Implicit Racism

Are you racist?

Now before you start saying, “No, of course not,” sit down and really think about it. Maybe it’s not the extreme type of racism, but the low key, guilty-thoughts kind?

Do you cross the street when you see a Black man walking in your direction? Do you assume that the Asian girl who sits next to you in your math course is acing the class? Do you get nervous when an Arab man sits next to you on the metro?

If you do, guess what—it’s not your fault, and having those thoughts doesn’t make you a bad person. In fact, it is practically unavoidable as a citizen of Western civilization.

It is important to realize you are thinking these thoughts as they happen, analyze them, ask yourself where they came from, why, and whether they are factual. Personal exposure to those of different races, ethnicities and cultures might decrease these judgements, in that it will humanize those of minority races.

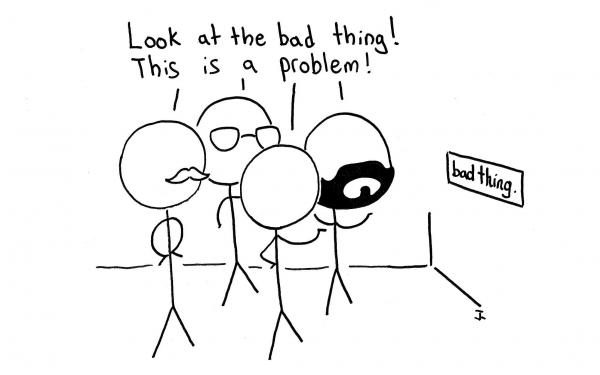

These thoughts are due to a collective mindset, known as “institutionalized” or “systemic” racism.

Institutional racism is a form of racism expressed in the practice of social and political institutions. It is also racism by individuals or informal social groups, governed by behavioral norms that support racist thinking and foment active racism. Whether implicitly or explicitly expressed, institutional racism occurs when a certain group is targeted and discriminated against based upon their race. Institutional racism can go unnoticed, as it is not always explicit and can be overlooked.

Having a friend or a significant other that is of a minority race does not excuse one from racist thoughts. Neither does being part of a minority race excuse one from systemic racist beliefs and ideas.

Institutionalized racism is woven into the fabric of society, and is hard to shake. Ideally, in a utopian world, these issues would have been solved long ago, and people of colour would have an equal chance in society compared to those of the majority. Unfortunately, this is not yet the case.

In an article called “White Fragility” from Huffington Post, Dr. Robin DiAngelo, a multicultural educator from Seattle, wrote, “mainstream dictionary definitions reduce racism to individual racial prejudice and the intentional actions that result.”

She explained that racism and being a good person have become mutually exclusive items. “But this definition does little to explain how racial hierarchies are consistently reproduced. Social scientists understand racism as a multi-dimensional and highly adaptive system—a system that ensures an unequal distribution of resources between racial groups,” DiAngelo concluded.

Institutional racism in Western civilization started with colonialism and continued to be propagated by longstanding stereotypes—an “unequal distribution of resources between racial groups,” as mentioned by Dr. Di Angelo, and a culture that posits whites as more relevant. This is prevalent in our education, with the centrality of European civilization and peoples in our textbooks, and our predominately white teachers and role models.

The perpetuation of racial stereotypes is also apparent in the media, with the negative or disproportionate representation of minorities in popular television shows and movies. There is also a disproportionate representation of minorities in seats of power, such as in the government—although that is gradually changing, for example with Justin Trudeau’s Canadian government and the Presidency of Barack Obama in the United States.

However, slow progress of racial equality does not negate the existence of institutionalized racism.

The stereotypes of the “angry Black woman,” “dangerous Black man,” “Muslim terrorist,” “drunken Native-American,” and “drug-dealing Latino,” to name a few, are still very real and present in our society’s mindset. These preconceived ideas of minorities can lead to larger, more violent consequences.

For example, the bomb threat at Concordia University on March 1, 2017 was aimed at Muslim students at our school. The shooting at the Quebec City mosque on Jan. 29, 2017 was again aimed at those who practice Islam.

Racial profiling by police is a real issue as well. According to the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, the Kingston Police began researching the issue of racial profiling in 2003. For one year, police officers were required to fill out a form whenever they made a traffic or pedestrian stop. After releasing their findings in 2005, they concluded that “Blacks were over-represented in police stops when compared to whites, and that Black residents were four times more likely to be pulled over by the police.”

In 2010, The Toronto Star conducted their own study of Toronto police and concluded that Black and brown youths were approximately three times more likely to be stopped than white youths between 2003 and 2008. The outlet discovered this out through examining the Toronto police practice of carding, which is the process of filling out a “208 card” with information on any individual stopped. The Toronto Anti Violence Intervention Strategy used 208 cards filled out by police to record information about persons “to be of interest.” These happened during both pedestrian stops and traffic stops. The Star’s conclusion: Black people filled out 41 per cent of the cards.

There are organizations in place to decrease these issues. For example, CRAAR, the Center for Research Action on Race Relations, is a Montreal based non-profit organization whose mandate is to promote racial equality and to combat racism in Canada. Since the year 2000, according to their website, CRARR has represented and assisted more than 1,000 people in different cities, advocating for victims of discrimination based on religion, race, ethnicity and citizen status.

Dr. Myrna Lashley, a professor in psychiatry from McGill, is another person speaking out on systemic racism. “The police are us. They reflect us, and we reflect them. […] We are the institutionalized racism,” said Lashley as panelist on a talk about institutionalized racism on Feb. 7 at Concordia.

How does it happen that we live in Montreal, and most students have never had an Indigenous teacher, she asked. “Why is it that we only know about Black people during Black History Month? Have you looked at your schools?”

We need the staff and members of our institutions to be racially proportional to the population, and, if they aren’t, Lashley said, we should stand up and ask why that’s not the case. That’s the start, she explained. Otherwise, in 10 years “we’ll be back here asking the same bloody questions, getting the same bleeding answers.”