Some Memories Should Remain Undocumented

Why Do We Obsessively Document Our Daily Lives, and What Does It Do to Us?

“Wait, wait! Don’t touch it yet, I have to take a pic first. Do you mind?” Just as I was ready to take a bite into my exquisite scone, I stopped, placed my fork back on the table, and positioned my plate nicely next to hers.

How many times has this happened to you when you’re out with friends? Maybe you even recognize yourself in this—you know who you are.

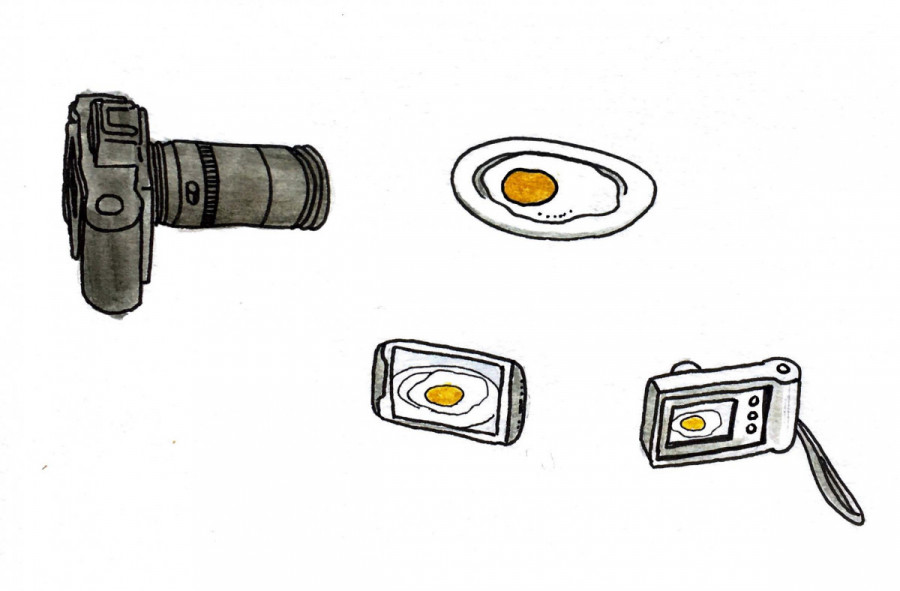

Cell phones have given us the ability to take as many pictures as we want, and it’s a blessing and a curse. We always have a tool to capture something extraordinary, but we lose touch with the meaning of photography.

Sometimes, a memory is more beautiful when it’s only in our minds. A photograph can ruin that.

As I sat there in the café that day, daydreaming about my delicious scone while my friend took 37 pictures of it on the table, I asked myself: “Why is she really doing that?”

Why did you take the last picture on your camera roll? Are you ever going to look at it again? The value of photography is lost somewhere between the immediate access to a camera and the extent to which we rely on it in our everyday lives.

We capture a moment to turn it into a memory. But what does this obsessive documentation reveal about ourselves?

What are we proving when we take a picture? And who are we proving it to?

The ideology of Gen Z has led us to believe that photographing a memory is essential and more valuable than the memory in our minds. Those pictures are either kept to ourselves as souvenirs or shared on the world wide web. Thorstein Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption would argue this obsessive habit’s objective is to prove our existence while creating an illusion of self-worth.

Once a trend becomes a mindless habit, we can forget how ludicrous it is. We stop questioning our actions because suddenly, it just seems like the normal thing to do. But it impacts how we live our lives, what we value and what we aim for. Most importantly, we begin to determine our self-worth from external validation instead of seeking it within ourselves. Over time, our reliance on it only increases.

Sometimes, I purposefully don’t record or photograph my experience at an event because I want the memory to exist as a thought rather than in a tangible form. That way, I am left with a feeling associated with the memory that I can romanticize, whereas if I document it, I place the task of remembering on empirical facts—the image—and therefore forget the feeling.

Immediate access to technology and its capacity to save our memories makes us lose touch with the experience itself because we rely on our blurry iPhone pictures to hold the entire feeling of a special moment.

Although keeping memories alive through a photograph evokes a certain sense of comfort, it also destroys the very essence of a memory because it is so tangible.

Joanne McNeil’s article “Tiny Proofs of the Existence of the Eiffel Tower,” published in The Medium, spells out the way technology shapes the art we create. McNeil makes a reference to David Wojnarowicz’s words, considering “intent” the primary motive of taking a photograph today. Photographing an iconic structure, then, serves as a method of personal documentation rather than practicing the art of photography. Is it to prove our existence? Or rather, a fear of forgetting?

McNeil calls the photographer’s intent, and therefore their relation to the photograph, “psychic metadata.” We take a shot of the Eiffel Tower not to have an amazing photograph of the architecture, but to keep a moment alive on a physical medium instead of solely relying on our memory.

In an era where everyone has a digital camera at their disposal, we do not need to think twice about the subject we are photographing. This luxury then changes the meaning and the value of photography.

Societal norms and mainstream media art determine the value we associate to a given artwork at a given time in society. What is beautiful now may not be beautiful in twenty or fifty years.

McNeil questions the validity or the relevance of a memory when the biggest part of the memory—the physical space—no longer exists, due to renovations or demolition in an urban landscape for instance. But she argues the feeling of missing a place, a home, a restaurant will never be quite the same as it was for previous generations because today everything is documented.

Although keeping memories alive through a photograph evokes a certain sense of comfort, it also destroys the very essence of a memory because it is so tangible.

And so, imagining the scene of a memory in its entirety is replaced by the physical material: a picture. The extreme reliance on objectifying moments in our lives renders “photographing […] a thoughtless gesture. We document in case we ever need a reminder,” McNeil wrote.

We keep nostalgia at a distance to alleviate the sadness it triggers by storing the memory in a photo, instead of taking the risk of forgetting it if stored in our minds.

Why do we document our lives? Where do we truly find meaning and value?

Experiences become a commodity with a certain social meaning attached to it. Suddenly, everybody is trying to create their own version of a commercialized experience. The value shifts from being the experience itself to being the product obtained from the experience—the material memory we take away with us.

There is a desperate need to document everything we see and a greater importance placed on advertising our experiences rather than enjoying the moment. A classic example is the live concert; we watch the performance through our tiny phone screens because our Snapchat story is obviously more important than the activity itself.

Andrew McGinely refers to the “if it’s not on Facebook it didn’t happen’’ mindset in an article he published in TheJournal.ie, drawing attention to the ridiculousness of a behaviour abandoning the connection to reality in order to pursue a connection to the virtual world. Throughout the article, he emphasizes the importance of living life—not simply being alive—and prompts the reader to reflect behaviour and relationship with technology.

We transform a memory, something that is immaterial and abstract, into something material and concrete.

All that in mind, whether we document our lives to prove our existence or to have something physical to hold on to, this art form has definitely shaped the actions and reactions of Gen Z to their way of experiencing life as well towards their appreciation of art.

Documenting that which is not worthy of documentation diminishes the connection to the experience. It creates an overabundance of insignificant details that are published to occupy the public eye. And in turn, it clutters our minds with meaningless expectations of validation. We face the danger of losing sight of what is really important.

Next time you take your phone out to take a quick pic, ask yourself if that scone is really worth a picture.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)