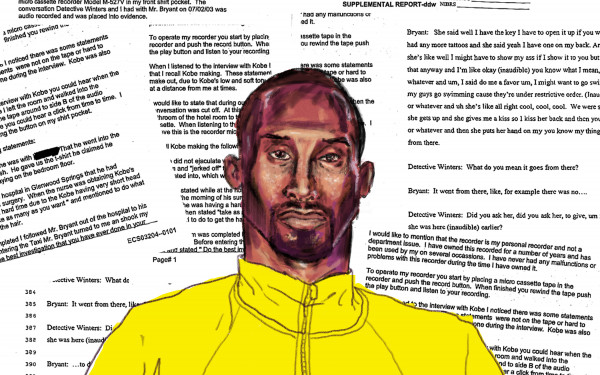

Rape Culture Is Real and It’s Time to Confront It

How an Open Letter to La Presse Reinforced Why it Needs to Go

On Feb 17, Michèle Ouimet—a well-known reporter from La Presse— published an article on the topic of rape culture. Essentially, Ouimet claimed that rape culture is not an issue in Quebec.

Compared to places like Afghanistan and Yemen, we should consider ourselves lucky, she stated in her article. Ouimet explained that she wonders whether today’s young feminists lack some historical perspective. She said women should perhaps look at past victories instead of grasping at the straws of today’s imaginary and futile battles.

The stance that she took was enough to get me angry, but it was the condescending tone that dripped from every word that pushed me to write an open letter in response. To my surprise, La Presse decided to publish it a week after the original article’s publication.

What was less surprising though, were the reactions and controversy my letter sparked. I tend not to get involved in heavy debates on the Internet, since they seem to be never ending and exhausting. However, I was curious, and no matter how ill-advised a decision it was, I decided to read some of the comments my letter had generated.

It was ironic to be on the receiving end of all these dismissive, hateful and violent comments. Ironic because most of the people who were strongly denying my experiences; denying that rape culture is rampant in our society and denying me my agency to write about it in an assertive way, were the ones proving its very existence and propagating its problems.

There were also a few women who had commented on my letter, saying that they had never experienced sexism and misogyny in their lives. Therefore, at best, they didn’t relate to my experiences, and that at worst, they just didn’t believe in them.

However, the overwhelming majority of the criticism I received came from men, who felt entitled to explain my own life to me. They dismissed the psychological violence and trauma that comes with being raped, claiming that it is not “real” violence. They defined microaggressions as “PC bullshit.” Some of these comments also stated that they missed when men could be men without being constantly called out by feminists.

What some people don’t realize is that rape culture is not only about rape. A lot of people focus on the word “rape,” when the word “culture” remains just as important. Many people have qualms about using the word “rape” in this context—this was one of the points that Ouimet had made.

She argues that using this word takes its power away. By overusing it, it will somehow lose its potency and become banal and meaningless. As if by addressing the question of rape culture, we will somehow diminish the question of rape and sexual assault.

There is power in words just as there is power in naming. Rape culture was first coined in the 1970s to address the commonality of rape and its societal and systemic normalization.

As with a lot of feminist concepts, “rape culture” has evolved to encompass more than just rape. It addresses a very toxic and pervasive reality in which female gender and sexuality are dismissed, diminished and degraded.

Rape culture affects everybody regardless of their gender, and it also affects people differently depending of their identities. One needs only look at all the disappearances of Black and Indigenous women without mainstream media even batting an eyelash to understand that racism and rape culture go hand in hand.

Saying that we live in a society that enables rape culture—that women, gender non-conforming and marginalized people are more often its victims than white cis-gender men—does not deny that men have the potential to be rape victims, and that women can potentially be rapists.

Rape culture encompasses how the concept of consent still needs to be spelled out, how catcalling as a form of street harassment is still controversial, and how victim-blaming and slut-shaming tend to be the norm when evaluating harassment, assault or even murder.

How “she was asking for it” is still more pervasive than “he assaulted her”; how “stay safe” rather than “don’t rape” is taught to young people; how rapists defend themselves by making statements on the beauty—or lack thereof—of their victims; how the blame is constantly shifted from the aggressor to the victim; how the policies, and sometimes even the laws in place, protect the perpetrator more than the victim.

Where a vast number of Black and Indigenous women’s disappearances are dismissed without a proper investigation; how women of colour are exotified and objectified; how Muslim women are assumed to be servile, obedient and unable to think for themselves because of their religion; how sex work erases the possibility of rape because “it’s their job”; how domestic violence is still not always taken seriously; how femininity is debased, criticized, scrutinized at every turn, and far more than masculinity.

This is rape culture. It still exists, no matter what these men commenting on articles have to say. It hasn’t magically disappeared, banished beyond the occidental world, to be confined in the countries we like to bomb in the name of “freedom.”

At the end of the day, one thing seems clear to me. These men are angry, yes—but also scared. Scared of losing their privileges. Scared of simply opening their eyes. Scared of realizing that the fabric of their world—of what they’ve always held as truth—is in fact threaded with white strands. Scared of acknowledging that they live in a bubble on the verge of exploding.

It doesn’t make it okay for them to confront their fear with hatred and abuse, but it certainly won’t stop me from trying to pop their bubbles in every way I can. I am done being scared, and I am done being silenced by their fear.

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)