Protest Denounces Federal Decision to Appeal Canadian Human Rights Tribunal Ruling

Ruling Awards Over $2 Billion in Compensation to First Nations Children Taken From Their Families

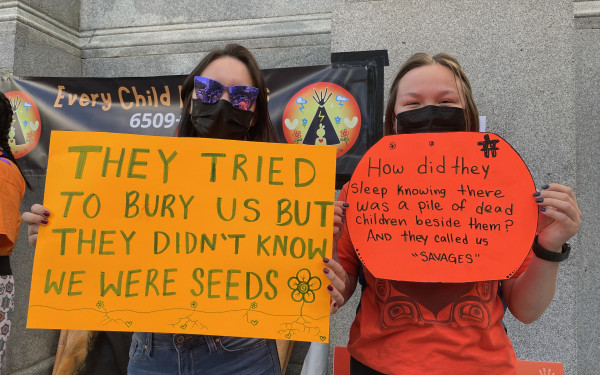

On Saturday afternoon in front of McGill’s Roddick Gates, dozens of protesters gathered in solidarity with Indigenous youth.

The demonstration was organized by Students’ Society of McGill University Indigenous Affairs. It comes in the wake of the Trudeau government’s decision to appeal the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruling ordering the federal government to pay over $2 billion in compensation to First Nations children who were victims of the child welfare system.

“These are kids who won’t get their childhoods back,” said Tomas Jirousek, commissioner of Indigenous Affairs at SSMU. “These are kids who have been separated from their culture and their families, because the federal government doesn’t think they’re worth the money.”

The ruling found the government “wilfully and recklessly” discriminated against First Nations children living on-reserve, as they failed to properly fund child and family services. Children living off-reserve typically had access to more resources as they were covered by provincial agencies.

“Canada was aware of the discrimination and of some of its serious consequences,” said the tribunal. “Canada focused on financial considerations rather than on the best interests of First Nations children and respecting their human rights.”

This led to the mass removal of Indigenous children from their homes and families. Even up until recently, Indigenous children have been over represented in the foster care system, making up 52.2% of the population of children in private foster homes in Canada. Indigenous children who have been in foster care face greater risk of poor health, violence, and incarceration according to Statistics Canada.

Those in attendance stood in a circle as individuals shared their experiences with the child welfare system.

Jo Roy, of the Abenaki First Nation, began with a story close to their heart.

“This is a story about resilience, but also a story about resilience that should have never needed to exist. It is resilience that has been present in many of our lives. This is a story about Ben,” they said.

Ben was born to Mary Jane Adam, a Dene woman, in the 1960s. When Ben was a baby, he and his three sisters were taken from their home, one by one, and sent to live in foster homes across Canada. They grew up in white families, away from their siblings.

Ben is the father of several children, and in 1998, he had three of his children living with him and his girlfriend. Two girls and one baby boy. As a survivor of the Sixties Scoop, Ben sometimes dealt with the lasting trauma of his experiences in a negative way. Seeing how Ben and his children lived and the environment he created for his family, the Canadian government decided to take his kids away.

“Instead of meeting Ben with compassion and love, something I am thankful that he later got from his sisters, the government just saw Ben as another stereotype and not for what he was,” they said.

The children were separated, just as Ben and his sisters were. The baby boy, Joseph, was adopted by missionaries and spent most of his life living in West Africa before moving to British Columbia, where he would graduate high school. In the summer of 2018, he moved to Montreal to escape, and a few months later, he met someone and fell in love. That person was Roy.

“This story represents the connection that we all have to each other. It shows that the harmful decisions of the federal and provincial governments do not just impact faraway communities,” they said.

“It is a pain that is woven into the fabric of our society and has cost us the lives of too many First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children. So please, don’t think that the pain of Indigenous peoples is far removed from your lives here in the city, because it is not.”

Nakuset, executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter, shared her personal experience as a child who was taken in the Sixties Scoop.

“I was taken far away from my community and brought here to Montreal, where I was forced to grow up in a culture that wasn’t mine and to be ashamed of my culture,” she said.

She spoke of how she was able to find the strength to go back, find her roots and get her status back. She was able to get an education and apply that by trying to change the systems that exist for Indigenous people in Montreal.

The difficulty, she explained, is the government’s discrimination of Indigenous peoples is global. They face federal discrimination through the Canadian government’s lack of funding for on-reserve children, and they face it provincially as well.

“What do you do? Right? When Trudeau came into power, he said he was going to implement [the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations], all 94 of them. He’s done 10,” she said.

Two hundred and thirty-one calls to justice were created in the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, many of them specific to Quebec because of the discrimination faced by Indigenous peoples in the province. A couple of weeks ago, the Viens report was released also including recommendations, a number of them focused on the child welfare system.

Nakuset stressed that, despite all of these recommendations and proposed solutions, there is nothing concrete to suggest that anyone is actually going to apply them.

“[Minister of Indigenous Services] Seamus O’Regan flies down to Attawapiskat this summer, and an eight-year-old girl approaches him and bursts into tears and says, ‘You don’t care about us, you’re just waiting for us to die,’” she said. “This is our youth, they understand that the government doesn’t care about us.”

Exasperated, she called for action.

“The fact that all of these recommendations have been put forward and no one is doing anything about it speaks volumes. So what are you going to do about it?”

She emphasized that citizens and allies of Indigenous peoples need to incite change, because the government is not going to just wake up one day and decide to follow these recommendations. It takes people to hold the government accountable for anything to change.

“Y’all are educated, you all have the opportunity to try to change the way the government is. If you put that effort in to tell them that you also think it’s wrong, and a mass of voices all come together, then they’re going to have to do something.”

With the federal election only one day away, consider that only a few of the major parties in the running have said that they will uphold the tribunal ruling. Both the Liberal and Conservative parties are in favour of a judicial review of the ruling, while the NDP has publicly denounced this stance and will accept the tribunal’s ruling.

The tribunal awarded the maximum compensation allowed under the Human Rights Act, $40,000 per child taken from their family for any reason that is not sexual, physical, or psychological assault between 2006 and 2017. It is estimated that the number of Indigenous children in the system during this time was between 40,000 and 80,000.