Making Art From Chaos: An Artificial Intelligence Poetry Reading

“Facebook Is in Love With Your Language. It Wants Your Minds,” said Concordia Alumnus David Jhave Johnston

“It’s incomprehensible, it’s a big wall, it’s like a cliff, and then it begins to change super fast,” said David Jhave Johnston. “The cursor works like a chisel at 6 a.m. in the silence.”

The digital poet has published 12 books of artificial intelligence poetry. As part of his practice, the digital poet dedicated two hours each morning for a year to his process of carving, a term he coined to describe the way that he cuts out undesired parts of computer-generated text.

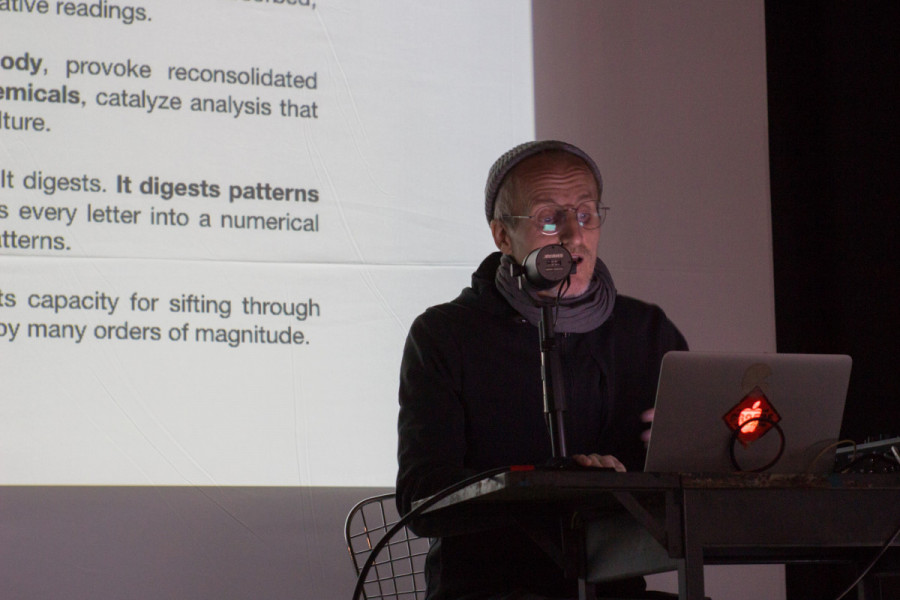

On Oct. 24, at Anteism Books, Johnston demonstrated how he produces poetry through an artificial neural network system.

Inside the dimly lit space, Johnston cut through lines of digitized blocks of text. He invited both audience members and poets to carve the text along with him. All at once, people were shouting words, making art from chaos.

The poets Simon Brown, Tanya Davis, and Victoria Stanton read from the tumbling excerpts on the projected screen, trying to catch up with the precipitation of words and carving them with their voices in the process.

“The views and opinions expressed by the following algorithms arise spontaneously from the conjunction of human corpus and statistical analysis,” said Johnston before the poetry readings, “and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the implement or artist—that’s me—or anyone else who reads them.”

Brown read between the electronic sounds produced by Alexandre St-Onge as they faded in and out during the performance.

Words, sentences, and sound were put together without coherence.

As for Davis, she read without hesitation. Her voice burst through the deluge generated by the AI, embracing the haphazard diction as the words dropped quickly on the screen.

RelatedStanton was more deliberate with her approach. Before proceeding to read the poetry, she asked the audience to take out their phones and play a song throughout her performance. A cacophony of different styles of music flooded the room as Stanton read from the laptop.

“I got a sense of what it was that I was going to read and the speed,” she explained. “I started hooking into certain parts of the texts and creating a narrative that came as I was looking.”

Stanton said that a narrative became more apparent as the text went forward. She latched onto specific words to create a sense of structure.

“It’s going to write poetry with extreme depth and continuity,” he said. “It is a fascinating time, I think, for literature.” — David Jhave Johnston

She believes that Johnston’s work is another form of found poetry.

“Traditionally, found poetry has taken the forms of listening to other peoples’ conversations, not necessarily in an obvious way but in a kind of discrete way,” she said. “Putting that together and creating poetry from these random bits and pieces: That’s found poetry.”

She stated there are various strategies and exercises that exist, like finding a newspaper on the street or in the garbage, and using the bits of text to form a poetic piece.

Related- The Words and Music Show Becomes a Digital Archive

- Vol. 40 Welcomes Back the Fringe Calendar Amongst Its Columns

“This for me is another continuation of that […] except it’s being generated by a different source,” said Stanton. “It’s coming from the screen, it’s coming from the software, it’s coming from the algorithms.”

Johnston also wanted the audience to interrupt and read from the projected screen’s influx of words.

People vocalized different words and sentences across the room, submerging the text in choruses of laughter and recitations.

Johnston explained that the first neural networking models that he worked with were much slower, only writing character by character. Johnston said that it would write about the smell of water, which he found “quite lovely.”

The poet now uses GPT-2, a strong algorithm.

He explained that the full-size GPT-2 model has yet to be released, but he played with the mid-sized model, using a poetry corpus.

“It writes in a more flexible vernacular, a kind of dementia,” he said. “All these streams of words, they’re good but they lack contextual sensitivity, continuity, awareness in body and structure.”

“I was going to say that I’m really afraid, and inside the word afraid is the word AI,” said Johnston about common fears regarding AI.

Johnston is more afraid of human aggression than the possibility of dangers in AI, he said. “[Our] bodies […] are capable of extreme compassion, and extreme cruelty.”

He said that AI is just another technological advancement that’s going to cause enormously beneficial changes and equally destructive ones.

Johnston carried on, saying that these advancements will change medical diagnostics, communication patterns, and also help paralyzed people walk.

“It’s going to write poetry with extreme depth and continuity,” he said. “It is a fascinating time, I think, for literature.”

“It’s becoming more coherent with time,” Johnston added. “Facebook is in love with your language. It wants your minds. It is eating them and digesting them—it finds them to be tasty.”