Invisible Labour

The Cost of Doing It All

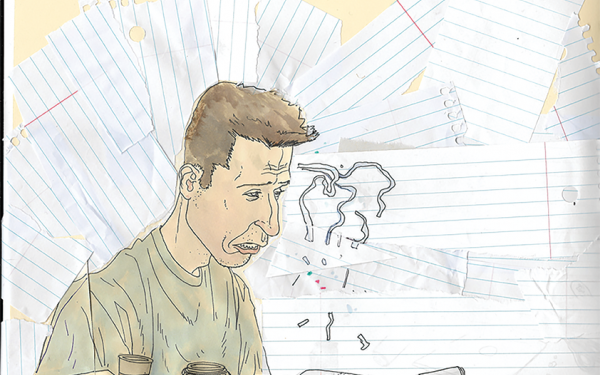

She has a great job, one that takes a lot of her time.

Work-life balance? She will talk about it at board meetings or during an interview with an eager applicant, before going home with a pile of paperwork and her work laptop.

Meticulously coiffed, rocking a freshly pressed blazer, everything a man can do she does backwards and in high-heels.

Wellness-at-work is her favourite buzz term, and she shows up to all the march-for-whatever-charity on Saturdays with her team, rocking the corporate swag.

On Sundays, she brings her 8-year-old to ballet and her 12-year-old to judo.

Everyone is impressed with her senior management role at the big corporation, a coveted position that she is trailblazing.

After work, she gets the kids from daycare and after-school sports, and heads home where supper must now be prepared.

She checks the fridge. “Where the hell is the milk?” Her husband must be doing overtime, but should be home around 6:30 p.m.

She texts him to pick up milk for supper and begins prepping the other ingredients in the meantime. She tidies up a bit, vacuums under the table.

She checks for the apron before starting the sauce. “Damn it, it’s still in the dryer.” There’s lint all over the bathroom floor, and her husband left the seat up.

She vacuums the bathroom, cleans the seat, and finally the timer in the kitchen goes off.

Her husband gets home, and he forgot the milk. “Why are you always nagging me, you have no idea what I do for you and this family, I put in twice the hours last week!”

“So? Why can’t you help around here?”

His phone rings. Great. She gets her keys, and leaves to fetch the milk. If she can’t get dinner ready by 7 p.m., the kids will destroy the pantry, her husband will make instant noodles, and she will miss evening yoga.

In the checkout line, she checks Instagram.

Her favourite mommy-blogger posted a new detox tea collaboration advertisement.

She rolls her eyes, as if this woman got her figure with no liposuction or personal trainer.

She laments that her stretch marks ruin the abs-look three years of yoga should have given her. At least she looks great in her new dress.

Does this woman sound familiar to you? Possibly. She’s made up, but could be someone you know.

I created the character from my own mother, coupled with a teacher of mine, and a former boss with a great job who simultaneously juggled her role with a husband and three kids.

These are women we all know. We can all think of a woman we know who does it all.

These are women we all know. We can all think of a woman we know who does it all.

Looks great, works hard, great mom and wife.

We all know of mommy bloggers who make work, social media content creation, raising kids, and maintaining a relationship look easy as pie.

We see those TV moms who are workaholics, vilified for not giving enough attention to their kids, and the stay-at-home ones covered in flour in the kitchen, working hard but listening to her husband’s stories about “a real job.” The new trend is do-it-yourself and doing it all.

What is invisible labour?

With all the buzzwords in feminist theory, we can have a tendency not to fully understand their meaning, and see them as nothing more than a label.

The woman I just described is a perfect example of an invisible labourer.

Everything she does when she steps out of the office is invisible labour, and this definition in intersectional terms can include much more.

According to The Atlantic’s article “The Invisible Labour Women Do Around the World,” in developing countries, women are largely excluded from economic improvements.

They cook, clean, look after kids, and even gather water or firewood in some situations.

We see this here too, to quote the article, “Women work more than men, even if a large part is relatively invisible.”

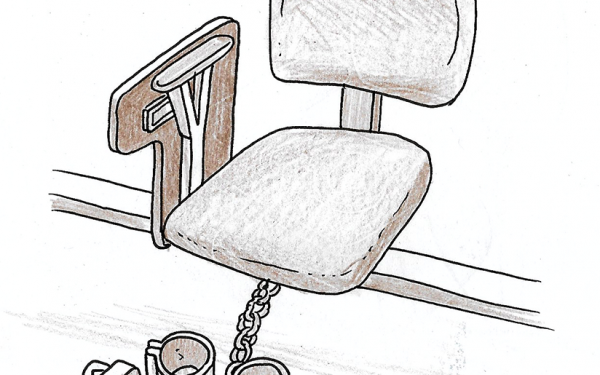

The United Nations found women do three out of four hours of unpaid labour and men do two-thirds of paid work.

The UN also found that women do 2.6 times the unpaid work that men would do, including caring for aging parents and childcare, balancing household expenses, and domestic work.

This is in addition to emotional labour, of course, balancing relationships, and carrying what is referred to as a “mental load.”

In the Forbes article, “How Emotional Labour Affects Women’s Career,” Gemma Hartley defines emotional labour as unpaid and invisible work that contributes to making those around a woman comfortable and happy.

She introduces other terms like “worry work,” which highlights that effort is put into emotional and mental obligations and commitments, which are often undervalued and not seen as work.

These add to a woman’s workload and can even seep into their career, and I’d assume this could increase the likelihood of burning out or mental health difficulties.

None of this is helped by a social media fueled society that only showcases the very best of people’s lives, where individuals market themselves constantly.

Of course, the sexual revolution and the women’s equality movement was extremely important and allowed women to enter the workforce in full throttle; where they went on to prove themselves as capable of the same level of work as their male colleagues.

In addition to all other societal expectations of women, however, they can then feel bad about their appearance, feel pressured to be Instagram fitness models, food bloggers, DIY queens, financially secure in a tough economy, all the while being well-dressed, and beautiful.

Books about being the best parent, best wife, best at work, and put together fill bookshelves.

Social media sensations have capitalized on this with inspirational videos and articles on how to be your best self and take control of your situation.

This can lead to a self-blame mentality, and a sense of shame over being unable to balance all of this, which adds to the emotional labour.

Counting calories and trying crash diets, feeling obligated to exercise instead of genuinely enjoying it, to maintaining relationships, to parenting “properly,” to be more involved at work, and keeping a nice home like in the magazines is hard work.

We need to recognize everything we do that is unpaid labour and wonder why we are doing it. Do we genuinely want to or do we feel obligated?

The first step to freedom is realizing what’s holding you back.

You can then fight back by refusing to perform unpaid work that doesn’t directly benefit you.

You can spot in advance the workload being imposed on you that you never asked for.

Remind yourself that you can refuse to put the happiness of those around you before your own, and you can refuse to believe what is marketed as reality that you do not see as realistically attainable.

Where there is a drive to profit from making people feel inadequate, the truest form of rebellion is to decide to be happy as you are and only do what you can manage.