Have You Ever Wondered What it’s Like to Act as a Racialized Person?

Two Actors Describe What it’s Like to Work in the Dramatic Arts

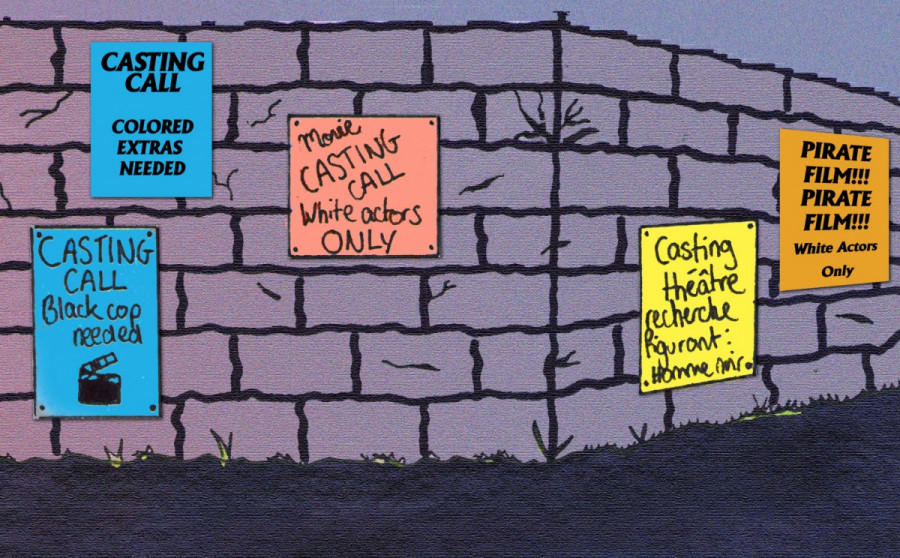

Not many people are excited by the thought of weekly rejection. But this is the professional actor’s reality, especially so for actors of colour.

Meet Kareem Alleyne and Alexandra Laferriere. Both are professional actors. Both are Black. Both worked (primarily) on the anglophone side of Montreal’s performing arts community.

“There is something to be said for people who are capable of going through rejection time and time again every week for the rest of their career,” said Alleyne, as he explained that the specific mental health issues faced by actors aren’t often understood by those outside of the community.

“We’re trying so hard to commit to a career that may not even happen,” he continued. Alleyne noted that many actors take on unenjoyable side jobs completely unrelated to their fields in order to support themselves.

Laferriere graduated from John Abbott College’s Professional Theatre program in 2012.

Around six years ago, she came to the realization that she wanted to dedicate herself fully to her craft and career. Like many of her fellow actors, Laferriere undertakes multiple side jobs to further her career, such as babysitting, retail work, and acting at a simulation centre, where she plays out scenarios involving health issues with students.

Laferriere explained the fundamental difficulty she’s faced getting her foot in the door. She tends to go on auditions every few months. She said the scarcity of the roles she’s cast for and given the chance to audition for tend to increase the sense of anxiety and pressure she feels.

“I find it [harder] when you don’t get a chance to get in the room. Having the opportunity to audition, that’s even harder than being rejected because that’s kind of your bread and butter, rejection. It’s the fact that you don’t get as many opportunities.

“If I was getting many and getting rejected and knowing that I put in the effort, that’s not as bad as just not having a chance to be seen.”

Laferriere doesn’t identify herself as a theatre or film actor.

“It’s kind of hard to have a ‘thing’ when there’s not much work out there,” she explained.

“It’s more like, what is being offered and I’ll find a way to do it. I’ve done plays and I’ve had day player roles in series,” she continued, a role that requires only a single day of filming.

Laferriere mainly auditions for English parts and can only remember going on one audition in French, which she didn’t get. Her experience of the French side is that it’s more competitive in contrast to the English acting scene here. She is fluent in the language, meaning that it isn’t an issue of expertise.

“Sometimes my accent in French can be a barrier. It’s already hard to find a lot of actors of colour in the French stage or even on Francophone TV.”

She said she feels like it’s just another factor that piles on to the fact that she is seen as the “other” for being Black, by creating an additional barrier for in pursuing French acting work.

Laferriere described a negative experience she had in relation to being asked to play a racial stereotype while out in the field, an experience that unexpectedly put her on the spot.

“They even wanted to pull up a video of said stereotype so I could imitate it. That made me a little sick afterwards,” said Laferriere.

Alleyne is one of the lucky few who figured out what he wanted to do at a young age: acting.

As a kid he loved acting in church or school productions, eventually pursuing a formal education in the dramatic arts.

Alleyne performs in both theatre and television or film, though he has a preference for the latter.Alleyne, who moved to Vancouver about seven months ago to continue his career there, said he’s had similar experiences to Laferriere.

Although he was interested in performing in French, his experience with that side of the acting world was that it was not progressive, noting that many roles he encountered focused on the stereotypical physicality of Black men.

Around three years ago he received an email from his agent saying he’d been booked for a role in a French television show. The only description of his character was “homme noir,” Black man. When he arrived at the set he found out his character was a gangster.

“I’m trying to understand why we’re putting the two together as one doesn’t equate the other. That was really hurtful for me to take a role like that because that’s something I never want to do, I don’t want to play roles like that. Especially one that doesn’t have substance because then you just become a prop on screen or onstage. You come in and you perpetuate a stereotype and you leave and I don’t want to do that. That’s not who I am as a person. That’s not who I am as an actor,” explained Alleyne.

He’s noticed that a lot the roles offered to Black men tend to share certain similarities.

“They’re playing a cop again, another strong athletic role where our physicality is showcasing to them that we’re capable of playing a firefighter, a cop or an army person. We’re rarely getting anything that’s a regular neutral person and because of that we’re continuing to perpetuate these stereotypes in Quebec media,” Alleyne said.

On the same set where he was asked to play a blatantly stereotypical character, he had another negative experience that he shared.

“I had an interesting experience on that set where the director referred to me and another actor as, ‘les deux Blacks viens ici,’ which translates to, ‘You two Blacks come here.’ I never in a million years thought I would be spoken to on set like that. At that time I was so early into my career still that I was kinda like ‘keep your mouth shut and move on do this day and move on’ and that’s it. I just told myself I’ll never work in a French production again. So I haven’t ever since,” explained Alleyne.

According to Alleyne, he started acting at a time when the industry was becoming more progressive. While he’s been involved with acting informally for most of his life, his professional career in the dramatic arts began in 2014.

“There’s way more roles for minorities and they’re not necessarily just still stereotypes. We’re having the opportunity to go out for things that have substance or that doesn’t showcase us in a negative light, which is great, so I definitely want to congratulate and commend the English industry for that,” said Alleyne.

“I will say, though, I think there’s still a lot of strides that need to be taken,” he continued.

While Alleyne stressed the importance of having more visual representation of minorities, he noted that change must come from behind the scenes—meaning there is still a pressing need for more representation of writers, directors, and producers of colour.

“We can change things on the screen but at the end of the day if behind the screen the writer is white and living a white life and is only going to write about white people, then the roles aren’t going to be there for Black people,” he explained.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)