First Voices Week Begins With Emotional Opening Ceremony

Week of Events At Concordia Highlights Indigenous Speakers and Artists

An audience listened intently as Charlie Patton vividly described a world in which there is no clean drinking water left. He explained that water, while appreciated, is taken for granted here, and asked that everyone take action to prevent the situation from worsening.

“We encourage the people to always remember when you put that glass to your mouth and you drink that water, how precious it is,” he said.

Patton, a Kanien’kehá:ka elder began the opening ceremony with a joining of the minds and an acknowledgement of the land, in the conference room of Concordia’s Hall building.

This event, along with the rest of the week, was coordinated by Concordia First Peoples Studies student, Shiann Whitebean, with the First Peoples Studies Member Association. This is the second edition, with the first having taken place in 2015.

He began the opening ceremony in Kanien’kéha, the language of the Kanien’kehá:ka. “[It’s] very important that we never forget [our] ways. It’s very important that we never forget our languages. That’s why wherever I’ll be asked to go, I always talk in my language first,” Patton explained to the audience.

Patton emphasized that while everyone in the room came from different backgrounds and “walks of life,” everyone was of “one mind” and should listen to and cooperate with one another.

He described their creation story of how “mother earth” came to be, and acknowledged all of the earth’s elements and gifts, such as the trees and the berries, and explained their significance.

“They all have their special responsibilities and ways, for some they are food, for some they are medicine, for some they are shelter,” he explained.

Patton spoke with a particular urgency, as he described water, an element that would become a recurring subject of the ceremony.

Members of the People’s Fire, a solidarity camp of Kahnawà:ke, also held a Standing Rock information session at the opening ceremony. Stacy Huff, who just returned from Standing Rock two weeks ago gave the audience an emotionally driven account of her experience at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests in North Dakota.

Seeing a teenager’s cry for help on Facebook back in July inspired Huff to go to Standing Rock. “I knew I was going. I could feel it. It was like a pull, and I knew I had to get there,” she said.

“Later on, I found out that there was thousands of other people that felt that pull,” Huff explained. “And eventually that’s what we called it—the pull.”

She told the audience how the camps of protesters, or “water warriors,” were divided into different skills sets, and how everyone would help each other. Some camps were for cooking, some for media, and others for the “arrestables,” which was a word she used to describe those willing to be arrested.

She was in the warrior camp at the front lines of the protest. Everyone’s aim was to shut down construction so that they’d lose money, she said. “That’s where it hurts them. In the pocket, financially […] so that’s where we had to hit them,” Huff explained. She encouraged everyone in the room to do the same, by divesting from banks.

Huff held back tears as she described her “worst day” protesting, when the military arrested protesters. She explained that the days grew increasingly violent after that, with people being shot at with rubber bullets.

She twisted her ankle as she was helping someone else up, and was carried to safety by other protesters. She watched from atop the hill as the military surrounded the protesters below, frustrated that she couldn’t be in the front lines.

“I couldn’t do nothing about it,” she said. “I was up there and I yelled and cried and I couldn’t do nothing. It was like watching a scene out of the 1800s.”

“The idea behind this is to create a space where we can share our perspective, where we celebrate Indigenous peoples and communities at Concordia and part of this broader community, where we can create dialogue and cultural exchange and deeper understanding,” Whitebean explained.

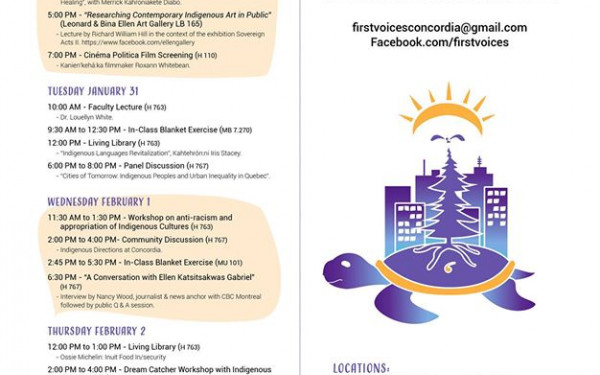

All events are led by Indigenous people, and are free and open to the public. The week includes panel discussions, living libraries, film screenings, and workshops until Feb 3.

“Later on, I found out that there was thousands of other people that felt that pull. And eventually that’s what we called it—the pull.” —Stacy Huff

She told the audience how the camps of protesters, or “water warriors,” were divided into different skills sets, and how everyone would help each other. Some camps were for cooking, some for media, and others for the “arrestables,” which was a word she used to describe those willing to be arrested.

She was in the warrior camp at the front lines of the protest. Everyone’s aim was to shut down construction so that they’d lose money, she said. “That’s where it hurts them. In the pocket, financially […] so that’s where we had to hit them,” Huff explained. She encouraged everyone in the room to do the same, by divesting from banks.

Huff held back tears as she described her “worst day” protesting, when the military arrested protesters. She explained that the days grew increasingly violent after that, with people being shot at with rubber bullets.

She twisted her ankle as she was helping someone else up, and was carried to safety by other protesters. She watched from atop the hill as the military surrounded the protesters below, frustrated that she couldn’t be in the front lines.

“I couldn’t do nothing about it,” she said. “I was up there and I yelled and cried and I couldn’t do nothing. It was like watching a scene out of the 1800s.”

“The idea behind this is to create a space where we can share our perspective, where we celebrate Indigenous peoples and communities at Concordia and part of this broader community, where we can create dialogue and cultural exchange and deeper understanding,” Whitebean explained.

All events are led by Indigenous people, and are free and open to the public. The week includes panel discussions, living libraries, film screenings, and workshops until Feb 3.

2_900_600_90.jpg)

_900_600_90.jpg)

5_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)