Editorial: Institutionalized racism persists against Indigenous communities

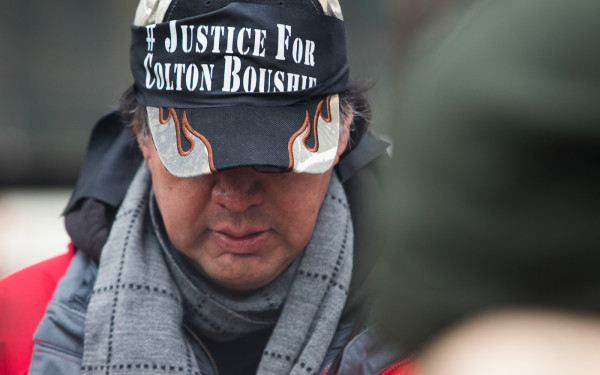

The death of Joyce Echaquan, which made waves across Quebec, is a painful reminder of the hatred and ignorance that is continuously manifested toward Indigenous communities.

The incident shocked many, yet it reflects a landscape of daily injustices faced by Indigenous communities, many of these anchored in stereotypes, prejudice, and other avenues of dehumanization. What’s more, far from an isolated incident, this case reveals systemic and structural racism that is latent in institutions beyond the police and schooling system.

Over decades, settlers imposed a new regime and way of life, completely disregarding those from whom the land was stolen. Subsequent generations of settlers, taught to hate and devalue lives based on race, internalized behaviour that continues to be manifested against Indigenous Peoples today.

Institutionalized forms of racism and inequality have transformed to fit changing social norms, but all it takes is a little questioning to see that it comes from the same rotten root.

Sept. 30 was Orange Shirt Day, an event created seven years ago to recognize the atrocities of residential schools and to commit to reconciliation. But a commitment is not a one-day thing. For allies, standing up for justice requires continuously educating oneself.

Around 150,000 children were forcibly removed from their homes and taken to residential schools, where generations were stripped of their cultural identity and many were abused.

The last residential school closed its doors in 1996, but the same spirit exists today through different institutions. Indigenous children make up 52.2 per cent children in foster care across Canada.

Similarly, Indigenous people make up more than 30 per cent of the inmates in federal custody as of January 2020, despite only making up five per cent of Canada’s population. This is an ongoing attack against identity, culture, land rights, and basic human rights.

The trauma and injustice toward Indigenous Peoples hasn’t stopped, it has simply changed its shape and taken on a different name.

As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report in 2015 acknowledges, genocide goes deeper than the physical one perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples; cultural destruction over generations and the gradual degradation and assimilation of cultures on an institutional level is also a form of genocide.

Meanwhile, only nine of that report’s 94 recommendations have been fully implemented—none in the area of health—as of December 2019, according to the Yellowhead Institute.

As Joyce Echaquan lay dying, the abject mistreatment and scorn she faced was not merely perpetrated by racist nurses. It is the inevitable result of institutional violence and a pervasive culture of ignorance, neglect, and dehumanization for which all settlers must take responsibility.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated for clarity.

3_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)