Editorial: Concordia’s Mangled Scramble Towards Sustainability

Global warming is creeping up on us from the foot of our beds: the shadow in the night, the ghoul in the closet, the Al Gore by your window.

Last Monday, the city announced it would spend more than $7 million taxpayer-dollars to try and save Montreal’s outdoor skating rinks from extinction. And all over the Arctic today, the icecaps risk melting.

We wonder when enough will be enough.

How much more will it take for institutions to realize the importance of sustainability and establishing systems that are long-lived and indefinitely productive: solar energy, wind energy and urban farming instead of fossil fuels and industrial agriculture.

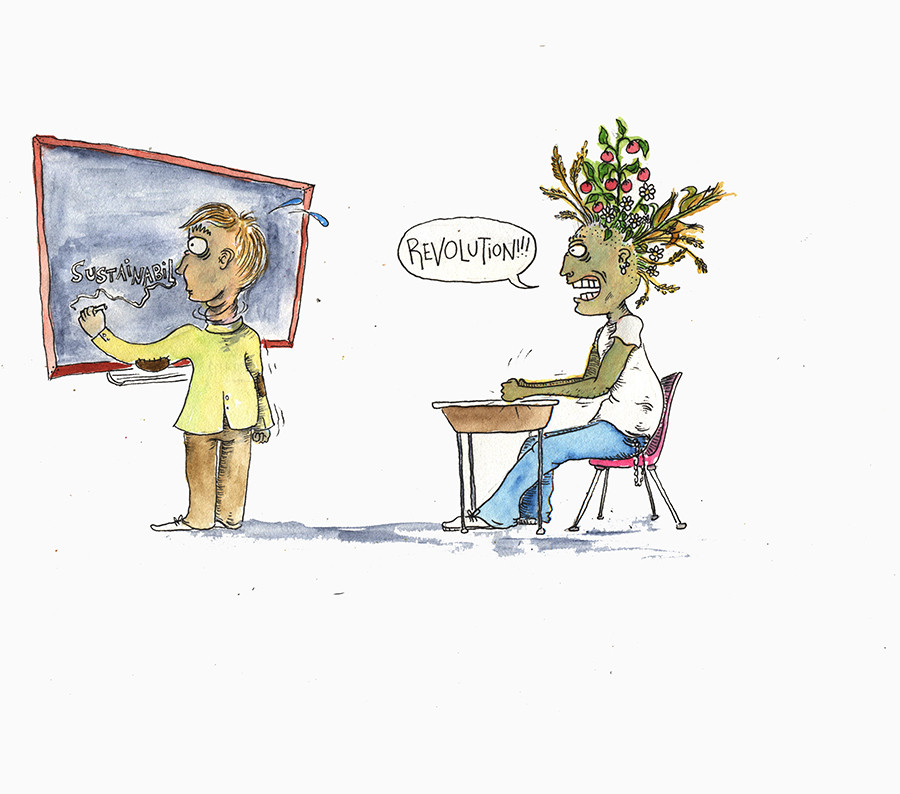

It all begins with education.

Sustainability should have been at the forefront long ago at Concordia, a university that brands itself as an environmental leader, with its pro-compost campaigns and decision to market itself as a “fair-trade campus.”

And we do believe it is a sustainability leader, albeit in branding alone.

In many ways, Concordia lags behind other universities in sustainability-orientated education. Instead of posturing, the university needs to push.

Over the period 2010 to 2014, the University of Waterloo in Ontario introduced more than 500 sustainability courses or courses that included a sustainability component. In 2010, McGill University began a new Bachelor of Arts and Science Program in Sustainability, Science and Society.

And on Thursday, Concordia’s Sustainability Action Fund held a workshop to push towards a curriculum for a new sustainability major at the university—a program a long time in the making.

In 2014, the SAF conducted a survey that discovered that, out of 2,129 Concordia courses, just seven per cent of them included a sustainability component.

And less than a year later, concerns were still brewing.

In May 2015, Trevor James Smith, an outgoing graduate representative for Concordia’s Senate, believed the university’s Strategic Directions treated environmentally sustainable initiatives as “niche topics.” The term “sustainability” was used once in the document.

Fast-forward to 2016, and we’ve only begun brainstorming how to have a sustainability program. The bureaucracy needed for this will take a few years to develop and, when created, only 30 students per year will be accepted.

That’s good, but it’s not good enough.

Today, most of the university’s sustainability initiatives are student-driven: the Hive, the Concordia Greenhouse, the Concordia Food Coalition. That could be largely because we, the students, think sustainability should be at the forefront and not tacked on the back end.

We at The Link believe the time is nigh: sustainability education should be less of an elective, and more of a core component entwined in every course. We advocate the idea of embracing “embedded sustainability,” akin to embedded journalism, where reporters latch onto military units for war reporting.

The war is raging today. It’s us against the world—a deteriorating globe, only worsened by our inclination for quick and easy, unsustainable habits. Sustainability education can and should be a part of all students’ courses, whether they study finance or fishing.

It has taken a combined effort for us to damage the planet to this extent, and it will require a combined effort for us to save it.

In Montreal, we know that winter is coming—or, as we reported, it will come but outdoor ice-skating may go. And we fear the time will come when we will no longer need to use the icebreaker: “How much does a polar bear weigh?”

If Concordia and other institutions that purport to care about sustainability and saving the environment don’t do as they say, and take sustainability seriously now, in a decade or two, there won’t be any ice for the polar bear to break.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)