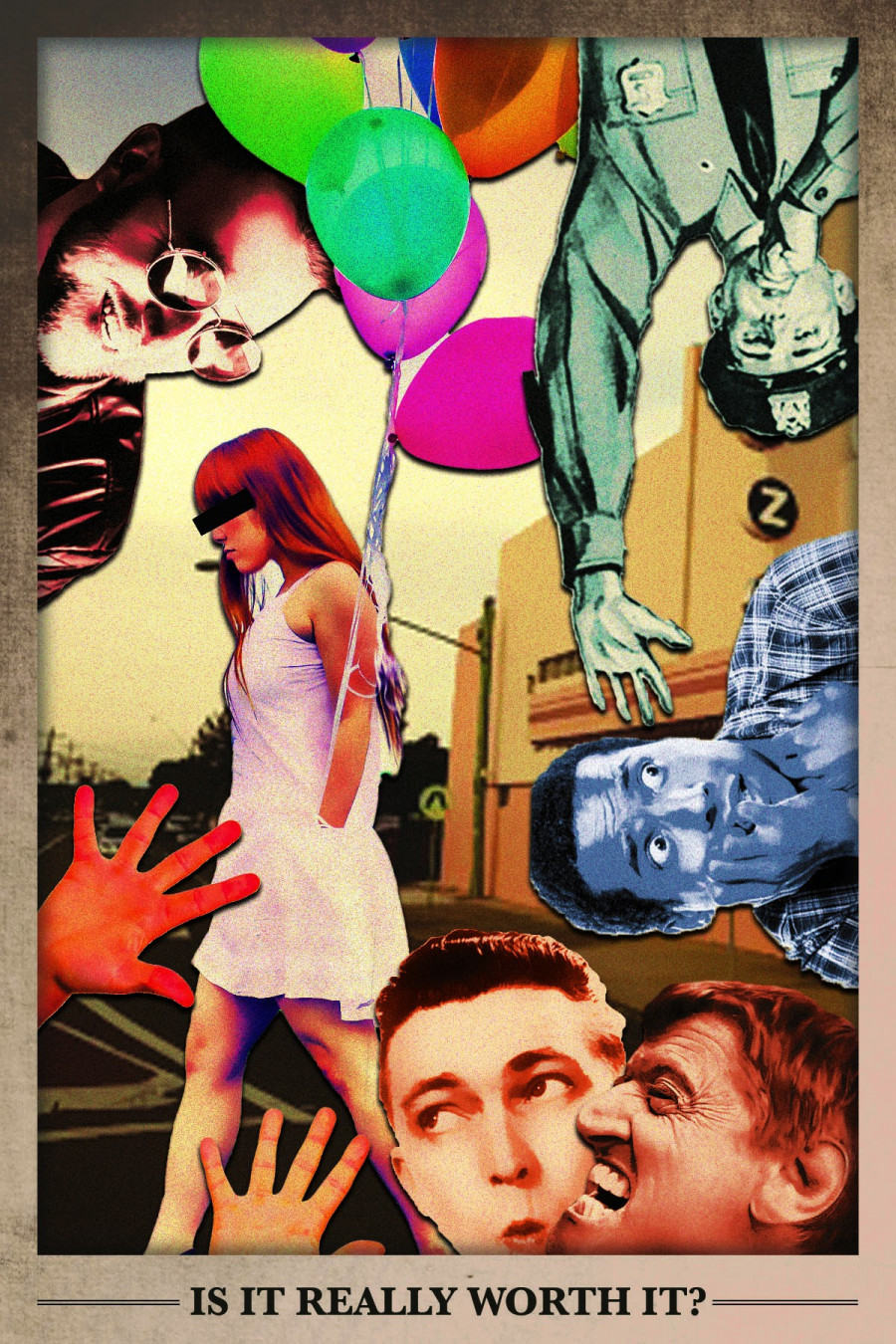

Catcalled Out

Quebec’s Green Party Proposes a Catcalling Ticketing Law That Falls Short

“Ladies, what do you think?” asks Alex Tyrell, the leader of the provincial Green Party, at the end of a Facebook post, intended to articulate and solicit public opinion for his party’s proposal.

It’s an idea for a new provincial law which would create a ticketing system for catcalling, enforced at the discretion of police officers. This would mean a fine of several hundred dollars—a sum that would increase if the catcaller was caught reoffending.

One little lady (me) thought at first that this was actually a good idea. But 0.2 seconds after that, I remembered that I actually understand how intersectionality works. Then I changed my mind.

First of all, this proposal does not seem to consider the intersectionality of people’s experiences while out in the space understood as “public,” where the proposed tickets would be handed out.

This proposal would see further state interference into people’s interactions while out in public. For people that belong to marginalized groups, that isn’t necessarily welcome.

People of colour are already stopped by police at a disproportionate rate compared to white people in Canada. The relationship between people of colour, especially men of colour, and the institution of policing is fraught with tension, stereotyping, and violence. The intersectional experiences of those who are catcalled and those who could be accused of catcalling are not being adequately considered within this context.

Historically women and men of colour have been the victims of conscious and subconscious bias by police who are supposed to protect and serve everyone.

When women of colour are catcalled, their experience of being racialized becomes a factor. Conversely, women of colour would likely be stereotyped when reporting catcalling to the police, because police officers are actually just regular people in uniforms with guns and the same ingrained societal biases as the catcallers. If this proposal were enacted, women of colour could expect to deal with officer bias towards them.

Women who are sex workers, drug users, unhoused, or undocumented may not want to invite further police presence, scrutiny, and interference into their lives by asking for the protection of reporting a catcaller. Theoretically, if members of these groups did report a catcaller, would their claims be taken as seriously as if they were a white, cisgendered, housed, non-drug using, documented person who was not a sex worker?

While catalling is absolutely a serious problem, it’s also subjective in its definition which means it could be subjectively enforced, resulting in innocent people persecuted.

I think that the innocent men who are more likely to be targeted would be racialized, along with the guilty men who are more likely to be punished. And I think that the victims less likely to receive help, belief, and support would be women of colour.

A 2017 study published by the American Psychological Association found that the results of seven studies proved that there is a stereotyped bias in how young Black men are perceived physically in comparison to white peers. Black men tend to be perceived as more imposing in every way: taller, heavier, more muscular, larger, stronger, and more capable of harm than white men.

This study suggests that this imagined need to physically subdue them could be one of the main reasons Black men are targeted by the police, even when they are unarmed and completely innocent.

Would the actions of men of colour potentially be perceived as catcalling in a manner that the actions of a White man would not? It’s likely that the answer is yes.

A 2016 study by the American Journal of Public Health found that Black men are three times more likely to be killed by police than white men. Hispanic men are twice as likely.To exist while being racialized means existing under a higher level of state scrutiny and surveillance. Creating this law could expose men of colour to more state sponsored violence and interference for behaviour that is catcalling (wrong) or not catcalling (right), but either way men of colour would likely be policed under the umbrella of this law in a manner that I don’t foresee affecting white men.

If this law were theoretically enacted and the tickets examined five years in, what story would that data tell? An egalitarian, rainbow, racial breakdown where the tickets issued to each racial group correlated exactly to the percentage they compose of Quebec’s overall population?

Or would it tell you the same story you and I already know?

The story that goes like: men of colour are targeted, victimized, and sometimes killed by the state for existing.

If the same theoretical examination looked into the complainants in each ticketing case, would white cisgendered women who appear to have class privilege be overrepresented, though they might not be the group catcalled as often as some others?

Would enacting this law really be a good idea, or legitimately be considered a progressive lefty-approved idea if it ends up targeting and further stigmatizing already marginalized groups?

This law could only be interpreted as progressive if it is reworked to provide for the differences in people’s lived experience. This proposal paints a pretty picture (protection for helpless ladies) without telling you what any of the colours are (enforcement of already ingrained societal bias).

I cannot claim to speak for all racialized people but I personally would not feel safe trying to ask a police officer for help if catcalled.

I don’t like living in a world in which I was catcalled as a 12-year-old child in my Catholic school uniform, accessorized with braces. I also don’t want to live in a world where someone could receive a ticket for doing that to me because I don’t think a ticket is the solution that would have removed 12-year-old me from those situations. Enacting and enforcing this proposal would take financial resources which are provided by taxpayers. I would rather see more resources be put towards solving the epidemic of unsolved, unreported, and unfounded rape cases.

I think more resources put towards educating people about rape culture, both in schools and for adults, could be a potentially viable and sustainable solution.

Enacting this law would give police officers discretion in their enforcement of it. While the law itself is not a terrible idea, people have biases. Police officers are people. Not superhuman objective stars that are somehow exempt from cultural bias.

We all live in a racist, patriarchal culture which leads to the development of subconscious biases that can only begin to be undone by conscious, ongoing, self aware reflection and conversation with likeminded people.

A 2017 Statistics Canada study on police-reported sexual assault paints a disturbing picture of rape culture’s effects on women. Many survivors, 87 per cent of whom are women, expressed concerns with the justice system as reasons for not reporting their sexual assaults. An estimated five per cent of rapes in Canada are actually reported to the police. Twenty-one per cent of those rapes end up being prosecuted to completion (but don’t assume the offender was fairly punished).

Some reported reasons survivors don’t report are: not wanting the trouble of dealing with police (45 per cent), the perception that police wouldn’t consider their assault important (43 per cent), and that their rapist wouldn’t be punished adequately or convicted at all (40 per cent).

Catcalling is a symptom of rape culture, not the other way around. If rape culture is understood as a societal disease it makes far more sense to put more resources to solve the lack of persecution and education surrounding the epidemic of unreported rape. A doctor does not treat a disease by addressing one symptom—they look for the cause of it.

Maybe if we lived in a society that actually wanted to punish rapists (what a crazy idea right?) instead of letting them roam around, women wouldn’t have to worry about being yelled at by creepy men who do not see them as autonomous individuals worthy of going about their days in peace.

I fail to see how it is empowering for me as a lady to run to a police officer for help. At a measly 32 per cent, Montreal’s police force still has one of the highest percentages of female police officers. So if this proposal was enacted, I would likely have to ask a male officer to ticket another man thereby solving the problem for me? No. No. NO.

What happens when a man isn’t there to “help” me by ticketing another man? How do I know I am not asking a male officer who catcalls women out of uniform to ticket someone else for doing that?

Using the logic of this proposal, I am left helpless and unempowered when a police officer isn’t there to receive my report. This proposal may not have been intended to be this way, but in practice I think it would only end up enforcing patriarchal racist values, which as a society we should be moving very far away from.

I do not feel empowered or supported by further state intervention into my daily life as well as the idea that the state will receive more money from this. Taking money from people doesn’t fix problems. It could actually make them more resentful. I think educating people changes attitudes.

I would be delighted to see a man with as much privilege as Alex Tyrell (with the support of an entire provincial party) stand up and say, “Hi, yes hello. The justice system is actually super fucked up. Men aren’t regularly prosecuted for rape and women are scared to report when it happens. Let’s fix this. Here are my ideas. Any thoughts?” But that hasn’t happened (yet).

A lady can only dream.