Brossard Family in Racial Profiling Case Urge for Changes in Policy

Five Year Case Highlights Long Wait Times at Quebec’s Human Rights Commission

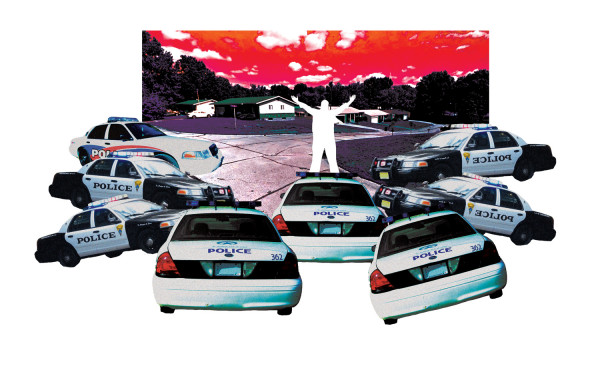

Over five years after Dominique Jacobs’ sons were brutally arrested by police officers who then violated the privacy of her home, the Quebec Human Rights Commission came to a decision, calling it racial profiling.

It was 1:30 AM when Jacobs heard the doorbell in the fall of 2013.

When Shaun James, Jacobs’ partner at the time, opened the front door there were four police cars and Constable Yan Massicotte entered with his partner Jordane Bérubé. They began searching the house with flashlights.

The officers brought Jacobs’ son, Terell Jacobs, who was 17 years old at the time, into the home and demanded to see his identification. His brother, Nathan Picard, was in the backseat of the police car outside.

Jacobs was told the boys were arrested for jaywalking and that they would receive a ticket in the mail.

The boys explained to Jacobs that while walking home, the officers had asked them “Ça va?” Being anglophone and not wanting trouble, the boys kept walking. After jaywalking, the same officers intercepted them and aggressively arrested them.

They said that Picard was slammed against the police car, punched, and thrown to the ground before being handcuffed and put in the backseat of the police car. They also said his brother was slammed against the car and threatened with pepper spray inches from his face when he asked what was going on.

According to the Highway Safety Code, the penalty for jaywalking is a fine of $15 to $30. When the police stops someone, they have to tell them why they’re being stopped, why they need the ID, and that they are getting a ticket.

Jacobs soon asked the officers for their badge numbers. She said while her home was searched, police either ignored or mocked her and her partner.

The officer repeatedly swore at her, she said, telling her to “shut the f- up” and “calm the f- down.”

The commission decided the family should be awarded $86,000 in damages from the city, and also made demands the Longueuil police create a plan to address racial profiling.

Cases like this all too common

Jacobs had to wait five years to hear her complaint of racial profiling was founded, but cases like hers are no exception. Fo Niemi, who has been at the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations for about 20 years, told The Link he sees cases like this all too often.

Earlier in 2018, he saw a case involving the City of Longueuil in which a Black man was constantly stopped for driving a BMW. His claim is $12,000. With Jacobs’ case, the city is looking at almost $100,000 in damage claims, not including the fees they’ll have to spend to defend themselves.

And right before Christmas, CRARR assisted in filed two new complaints against the Longueuil police for a Black couple who experienced similar treatment last summer, having police barge into their home and mistreat the couple.

Many like Niemi have criticized the Quebec Human Rights Commission saying cases take too long to close. Jacobs described the process as long and frustrating.

“I felt like no one was taking this seriously,” she said.

“There were other incidents over the last five years,” Jacobs said. “If this had […] been dealt with right away, maybe it could have prevented other situations with other people who had to go through the same type of thing with the Longueuil police department.” –Dominique Jacobs

Meisson Azzaria, the communications director of the Quebec Human Rights Commission, said racial profiling cases are always more complex and so take more time because they involve consultation with police.

To prove racial profiling, there must be proof that the police intervention was based on the race of the person but when it comes to racial profiling, the policeman won’t say “oh I just stopped you because you are Black,” Azzaria explained.

The commission is demanding Longueuil police update their action plan against racism and discrimination, that they adopt measures to detect and control signs of racial profiling, and that they provide anti-racism training.

Though the decision made by the Human Rights Commission is non-binding, the Human Rights Tribunal has the power to enforce it.

Jacobs’ case is now being brought to the Human Rights Tribunal. Though no date for a hearing has been set, Niemi said it should be in the spring or summer of this year.

“You cannot just walk into people’s homes, you need legitimate reason and you must treat people not only with respect but within the boundaries of the law,” Niemi said.

Canada’s Charter of Rights says a person’s home is inviolable. Niemi said the incident was an obvious intrusion and a violation of the family’s privacy.

Though Jacobs and Niemi hope the large sum of money might force the city to take responsibility, what they are really happy about are commission’s demands for reforms.

At first, CRARR helped file a complaint to the police ethics commissioner for police misconduct, but the commissioner didn’t want to investigate as they didn’t see anything wrong with what happened to Jacobs’ family, Niemi said.

They challenged that decision and the commissioner said they’d send the complaints to conciliation. Afterwards they closed the file because the commissioner said he didn’t think he could prove the allegations in court, “which felt like a ridiculous reason,” Niemi said.

He added that this case raised questions with the police ethics commission and their ability to recognize racial profiling and deal with it accordingly.

“They don’t have a policy guideline on what is racial profiling,” he said. “When they get a complaint it looks at traditional perspectives on whether it’s police misconduct or not.”

Starting the process over again with the Quebec Human Rights Commission meant the beginning of another long and complicated journey.

When assessing a case, the Quebec Human Rights Commission looks to see if the Charter of Rights was violated, then contacts the other party to advise them that a complaint has been filed against them. There is a possibility of mediation—and if both parties come to an understanding, the file is closed.

In cases of racial profiling, the police is represented by lawyers and mediation typically isn’t an option, which lengthens the process.

When the Human Rights Commission begins an investigation, it can take months for an investigator to be assigned to a case. Once the investigation is over, a committee will then come to a decision and ask for damages. The other party receives a notice, which they have 30 days to respond to on average.

Once the case is brought to tribunal, the Quebec Human Rights Commission represents the plaintiff as a free service. The decision reached by the judge is final and legally binding.

The time it takes for mediation, longer investigations, needing legal advice, and the wait time for the other party’s response all play a role in how long a complaint is studied, Azzaria said.

“When it comes to racial profiling, you have to look into how the event happened and gather many details and find the witnesses and get their version and comment on other versions and that can make the case take longer,” said Azzaria. “We do all we can to make it as short as possible, but racial profiling is complex.”

However, she said that the Quebec Human Rights Commission has gotten some new resources, including more staff.

With the training of new staff and giving priority to longer files, Azzaria said the average time to process cases should go up.

“It takes time to see results even if we make changes,” said Azzaria. “In the last few months we had more people coming in but by the time these people are fully trained, we won’t see the results in the next six months but in the long-term it will make a difference.”

She said the less complex cases are still being closed within about three years.

The Human Rights Commission is also planning to implement an online complaint form to make it easier for people to take the first step and see if the commission can intervene.

Niemi added that in most cases police will not comply with the decision made by the commission, and that police tend to use a lot of procedures to complicate or delay the proceedings.

“Justice in this province is very long,” he said.

“If the system doesn’t work for you, you have to change the system… We have to challenge it when the Quebec Human Rights Commission takes five years to investigate this”

Reforms and Systemic Change For Longueuil

In 2015-2017, the Longueuil police force put out an action plan to combat racial profiling.

However, it’s very difficult to find any public documents describing what has been done. Police didn’t respond to requests for interviews.

“We couldn’t even find the name of the advising committee that was supposed to be made,” said Niemi. “There is no trace of the action plan being implemented. So the commission will probably demand that it be implemented.”

The commission asks that there be anti-racist training instead of cultural sensitivity, narrowing it down to anti-discrimination training plus an accountability framework or evaluation after the training.

Another important remedy proposed by the commission is to ensure that the recruitment and promotion selection of police officers are based, among other things, on cross-cultural competencies.

“In other words, if you have bias of any kind, not just race and ethnicity, you should be identified […] and even denied a job because it’s incompatible with being in a position to serve the public,” said Niemi.

Niemi added that he sees a lot of young people either refuse to come forward or give up because they feel the system doesn’t work for them. But, he said, if more and more people come forward, the system eventually buckles and implements changes.

“The police department will break down because the people are always right,” he said. “When people start to come out in great numbers to take action, the system will change.”

The Charest government, which made the fight against racial profiling part of its campaign platform in 2003, set up a task force to develop policies surrounding racial profiling when it got elected. In 2005, the first Black judge in Quebec recognized that a Black man was a victim of racial profiling for the first time in criminal court in Montreal. In 2006, the Quebec Human Rights Commission had its first ruling of racial profiling.

“That’s how we change the system, not only by reforming and bringing new people, but by bringing the right ideas and knowledge and keep the outside pressure on the sustainable level,” said Niemi.

And when people like Jacobs go through with the process, no matter how long, it highlights the problems within the system.

“I never felt like giving up,” Jacobs said.

“I know there are other parents out there who will feel the same way. If I just say ‘I can’t handle this anymore, I’m done’ that tells the boys to just give up if it doesn’t work. I want them to know that somebody is there to protect them,” she said.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)