The Black Speculative Arts Movement Convention and the Importance of Black Art

Afrofuturism and Cultural Appropriation Took Centre Stage During the Panel

The Black Speculative Arts Movement of Montreal featured a series of panelists for a discussion panel made up of Black artists and creatives last Friday, in an event that was enlightening, educational, and empowering.

The talk was centered around the genre of afrofuturism, which is the intersection of the culture of the African diaspora and technology. Afrofuturism combines elements of science fiction and fantasy, and can be used to critique current racially charged dilemmas Black people may face. As well as discussing afrofuturism, the panelists made sure to discuss how to further it in the Montreal art scene.

“The artists here who are creating work have such a unique perspective, and it’s with these conversations that we realize there’s a void that can easily be filled by ourselves,” said host for the evening and organizer for previous BSAM Montreal events, Quentin VerCetty.

He was full of pride for the event, and the positive impact the convention and others like it will surely have on the art scene in the city.

The event was held in McGill University’s art building, thanks to the combined efforts of McGill’s Black Student Network and the African and Caribbean Student Network of Canada at Concordia.

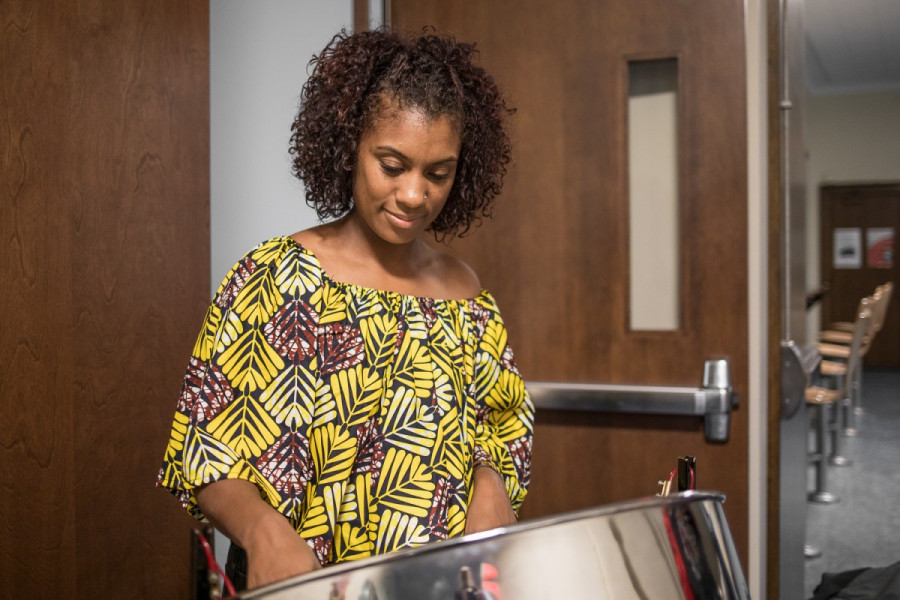

The evening was a powerful affair of love and admiration for Black artists; art vendors displayed and sold many works, there were steel drum performances and some attendees were in cosplay.

During the panel discussion, visual artist Jonathan Fado spoke about the integration of the Black population into popular culture, in regards to the recent Marvel Studios’ Black Panther. It was the studios’ first film with a predominantly Black cast, and the highest grossing film by a Black director.

“It’s bigger than putting Black people on TV just to try something new, it’s opening a door of hope,” Fado said.

It would be negligent for a conversational event of this sort, held between a varied group of artists of colour mostly from the Montreal area itself, to not speak on the effects and issues of cultural appropriation in the Montreal art scene. And with such a topic, it would be just as negligent to avoid mentioning the controversial show SLAV.

The theatre piece, which was eventually “cancelled”:httphttps://thelinknewspaper.ca/article/controversial-jazz-festival-show-slaav-cancelled due to immense push back, was featured at the Montreal Jazz Festival during the summer. The play, based on the stories and songs of Black slaves during the transatlantic slave trade, mainly featured white actors throughout the performance. This controversy of cultural appropriation was discussed at length by panelist Elena Stoodley, a Montreal artist who recently performed at Pop Montreal.

“It’s bigger than putting Black people on TV just to try something new, it’s opening a door of hope.” —Jonathan Fado

Stoodley also discussed the various protests that erupted because of the performance, and the complaints received after the play was ultimately cancelled by the Montreal Jazz Festival (with people calling the cancelling of the show an attack on artistic expression).

When audience members at BSAM Montreal were asked by Stoodley why they didn’t feel inclined to see the show SLAV , the verdict was simple: why go see white people sing songs and make money off of Black pain?

In thinking of the future of Black artivism in Montreal, the event also paid homage to its past, with the help of Stoodley, and Uchenna Edeh, another visual artist and firm advocate of afrocentric storytelling. They made a point to revisit the 1968 Montreal Congress of Black Writers, a landmark event that caused a very tangible shift in Canadian Black consciousness.

Over the course of four days in 1968, hundreds of Black writers, philosophers, and revolutionaries met at McGill University to further the conversation of radical black politics. This was invigorated by the Black Power movement in the United States and news of an incident in Canada; where custodians at a cemetery in Nova Scotia prohibited the burial of a young Black girl due to a company bylaw, which dated back to the early 1900s, forbidding the burial of Blacks and Indigenous peoples.

Edeh sounded-off on the need for Black people to tell their own stories, without waiting for the white masses to do it for them.

“It’s important for Black people across the diaspora to control our own narrative,” said Edeh. “People are always talking about ‘Why isn’t there a holiday for Malcolm X?,’ for example. Well, if you want to start a Malcolm X holiday, then don’t go to work that day. Tell all your friends to do the same. That’s how we control our own narrative, without waiting for people to give us permission.”

As diverse as schools like Concordia and McGill may be, it’s still difficult for students of colour to find representation in their own student body. This makes our schools feel more like predominantly white institutions rather than the inclusive cultural centres administrations would have us believe.

This is why events like BSAM are important; they provide a platform for Black artists, and help other Black artists get in touch and build an essential community.

“We do hope for events like these to get bigger, and for it to be supported institutionally, and community-wise as well. Because that’s the only way we can get the change that we want to see as artists, as a community,” VerCetty explained. “We want to be included in other conversations, have our work included in other galleries and spaces; we don’t want to have to doing everything ourselves. These institutions aren’t looking out for us.”

“I’ve had a lot of issues within animation, where I’m trying to write our stories, and people are questioning the entire process,” said Fahad, an animation student from the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema at Concordia who only gave their first name.

“I’m trying to defend my standpoint because no one understands where I’m coming from [growing up as a Black man],” continued Fahad. “From now on, I’m not going to worry about whether or not other people understand, I’m just going to make it for the people who will understand, because they need that kind of content.”